- 141

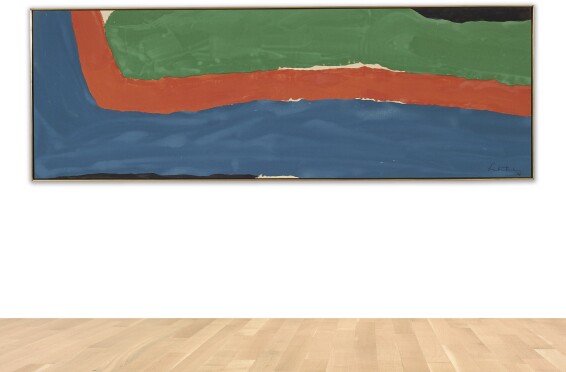

HELEN FRANKENTHALER | U-Turn

估價

500,000 - 700,000 USD

Log in to view results

招標截止

描述

- Frankenthaler

- U-Turn

- signed and dated '66; titled on the stretcher

- acrylic on canvas

- 33 by 97 3/4 in. 83.8 by 248.3 cm.

來源

Acquired directly from the artist by the present owner in 1974

Condition

This work is in very good condition overall. There is light evidence of handling along the edges. The colors are bright, fresh and clean. Under Ultraviolet light inspection, there is no evidence of restoration. Framed.

In response to your inquiry, we are pleased to provide you with a general report of the condition of the property described above. Since we are not professional conservators or restorers, we urge you to consult with a restorer or conservator of your choice who will be better able to provide a detailed, professional report. Prospective buyers should inspect each lot to satisfy themselves as to condition and must understand that any statement made by Sotheby's is merely a subjective qualified opinion.

NOTWITHSTANDING THIS REPORT OR ANY DISCUSSIONS CONCERNING CONDITION OF A LOT, ALL LOTS ARE OFFERED AND SOLD "AS IS" IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CONDITIONS OF SALE PRINTED IN THE CATALOGUE.

In response to your inquiry, we are pleased to provide you with a general report of the condition of the property described above. Since we are not professional conservators or restorers, we urge you to consult with a restorer or conservator of your choice who will be better able to provide a detailed, professional report. Prospective buyers should inspect each lot to satisfy themselves as to condition and must understand that any statement made by Sotheby's is merely a subjective qualified opinion.

NOTWITHSTANDING THIS REPORT OR ANY DISCUSSIONS CONCERNING CONDITION OF A LOT, ALL LOTS ARE OFFERED AND SOLD "AS IS" IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CONDITIONS OF SALE PRINTED IN THE CATALOGUE.

拍品資料及來源

Helen Frankenthaler’s U-Turn is an alluring and evocative declaration of this great artist’s mastery of color as the primary aesthetic core of her work. As the cornerstone of her enduringly influential painterly style, color was employed variously as shape, space, figure, ground or subject. As in the best works of other Color Field and Abstract masters such as Mark Rothko and Morris Louis, Frankenthaler’s U-Turn embodies the overall clarity, vividness and density of the blue, green and red palette which is the heart of this painting, pulsing with opaque areas of bright color. Painted in 1966, U-Turn is also an exemplar of Frankenthaler’s move toward edge-to-edge color in vivid acrylics, and away from centralized figures and forms against an unpainted background, as evidenced in her earlier oil paintings such as Mountain and Sea. Frankenthaler’s early reputation began to build within only a year after her graduation from Bennington College, and her appreciation for the “wild”, “brilliant” and “exciting times” at her alma mater are a consistently significant subject in relation to Frankenthaler’s artistic education and early inspiration. In the case of U-Turn, there is an even stronger connection with her college years. Long after Frankenthaler left Bennington in 1949 as a promising young talent, she remained friends with Sonya Rudikoff, a fellow graduate and close friend also interested in art and art history. In 1950, Rudikoff and Frankenthaler shared a studio apartment in New York and from these beginnings, a deep friendship continued throughout their lives. Rudikoff went on to a respected career as a scholar of Victorian literature and as a writer and literary critic, most prominently as an editor and contributor to The Hudson Review. Over 500 letters and postcards between these two friends, dating from 1950-1997, were donated to Princeton University. The current owners were also good friends with Sonya Rudikoff, who introduced them to Helen Frankenthaler, and as referenced in her correspondence with the artist, a visit was arranged at the artist’s studio in Spring 1974. At that time, U-Turn was acquired by the present owners in 1974 and has not been seen in public since that time.

In the early 1950s, Frankenthaler quickly established a reputation as one of the most promising artists of her generation with her first one-person show at Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York. The next year, she was the youngest artist included in the momentous Ninth Street exhibition, and one of only three women artists in the show along with Grace Hartigan and Joan Mitchell. This watershed exhibition in 1951 was organized by the rising New York downtown artists, led by Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline and Leo Castelli, who sought to proudly proclaim the importance of their avant-garde achievements in the post war era. While her inclusion in the show signaled Frankenthaler’s acceptance by her peers as a highly regarded member of the “second generation” of Abstract Expressionists, she had long sought to establish her own unique style that would synthesize the Cubist traditions she had absorbed at Bennington College in the late 1940s, with the challenging accomplishments of such colleagues as Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky and de Kooning. Frankenthaler achieved this glorious breakthrough in the following year when she first brushed turpentine-thinned oil paint onto unprimed canvas, forging her own innovative path in the masterpiece, Mountains and Sea (1952, Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.). Leaving behind the expressionistic, textured brushwork of her work of the late 1940s, colors now stained her canvas, with the color forms creating the shape and spatial rhythms of her paintings. As Morris Louis stated in 1953, after he and Kenneth Noland viewed Mountain and Sea in Frankenthaler’s studio, Frankenthaler was “the bridge between Pollock and what was possible” (as quoted in John Elderfield, Helen Frankenthaler, New York, 1989, p. 65). Noland and Louis were both greatly influenced by this early visit, which marked Frankenthaler’s undisputed role in the rise of Color Field painting as a new form of expression in paint.

By the 1960s, Frankenthaler was ready to move in new directions, away from compositions that had centralized color forms in almost figurative or semi-landscape shapes. By the time she painted U-Turn in 1966, Frankenthaler’s forms were more simplified and more expansive toward the edge of her picture plane. As John Elderfield observed, “The muted, delicate, sometimes rusty tonalities of the late 1950s sharpened into more saturated, intense hues, including prismatic colors, sometimes heightened by the use of dense blacks… [Color] as such – as hue – did gain prominence… She used fairly heavily applied color at times, too. Even by the end of 1961, she was talking of moving away from a ‘very thin stain’ to paint that, while still allowed to ‘get into a pool… is thicker and more compact.’” In abandoning the use of large tracts of exposed canvas in her compositions, Frankenthaler focused more intimately on the color relationships of her palette, bringing her into the company of other master colorists, such as Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still and Hans Hofmann, who celebrated the force of color from edge to edge of their canvases. In addition, Frankenthaler turned to the use of acrylic rather than oil in the early 1960s, which she found to be “not as involved in métier, wrist or medium as is often the case with oil. At its best, it fights painterliness for me… Moreover, her turn to using acrylic was part of a ‘struggle for me to both discard and retain what is gestural and personal’” (John Elderfield, ibid., p. 166).

U-Turn dates from this consequential period of Frankenthaler’s work, when she had fully succeeded in independently forging her own aesthetic that was neither Color Field nor Abstract Expressionism. The late 1960s were a time of critical acclaim for Frankenthaler when the Whitney Museum of American Art organized her first retrospective in 1969 and renowned curator Henry Geldzahler selected her as the sole female artist in his seminal survey exhibition of New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her unique and deeply instinctive gift for coloration was fully recognized in the 1960s, and continued throughout her long career and into the 21st century.

In the early 1950s, Frankenthaler quickly established a reputation as one of the most promising artists of her generation with her first one-person show at Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York. The next year, she was the youngest artist included in the momentous Ninth Street exhibition, and one of only three women artists in the show along with Grace Hartigan and Joan Mitchell. This watershed exhibition in 1951 was organized by the rising New York downtown artists, led by Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline and Leo Castelli, who sought to proudly proclaim the importance of their avant-garde achievements in the post war era. While her inclusion in the show signaled Frankenthaler’s acceptance by her peers as a highly regarded member of the “second generation” of Abstract Expressionists, she had long sought to establish her own unique style that would synthesize the Cubist traditions she had absorbed at Bennington College in the late 1940s, with the challenging accomplishments of such colleagues as Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky and de Kooning. Frankenthaler achieved this glorious breakthrough in the following year when she first brushed turpentine-thinned oil paint onto unprimed canvas, forging her own innovative path in the masterpiece, Mountains and Sea (1952, Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.). Leaving behind the expressionistic, textured brushwork of her work of the late 1940s, colors now stained her canvas, with the color forms creating the shape and spatial rhythms of her paintings. As Morris Louis stated in 1953, after he and Kenneth Noland viewed Mountain and Sea in Frankenthaler’s studio, Frankenthaler was “the bridge between Pollock and what was possible” (as quoted in John Elderfield, Helen Frankenthaler, New York, 1989, p. 65). Noland and Louis were both greatly influenced by this early visit, which marked Frankenthaler’s undisputed role in the rise of Color Field painting as a new form of expression in paint.

By the 1960s, Frankenthaler was ready to move in new directions, away from compositions that had centralized color forms in almost figurative or semi-landscape shapes. By the time she painted U-Turn in 1966, Frankenthaler’s forms were more simplified and more expansive toward the edge of her picture plane. As John Elderfield observed, “The muted, delicate, sometimes rusty tonalities of the late 1950s sharpened into more saturated, intense hues, including prismatic colors, sometimes heightened by the use of dense blacks… [Color] as such – as hue – did gain prominence… She used fairly heavily applied color at times, too. Even by the end of 1961, she was talking of moving away from a ‘very thin stain’ to paint that, while still allowed to ‘get into a pool… is thicker and more compact.’” In abandoning the use of large tracts of exposed canvas in her compositions, Frankenthaler focused more intimately on the color relationships of her palette, bringing her into the company of other master colorists, such as Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still and Hans Hofmann, who celebrated the force of color from edge to edge of their canvases. In addition, Frankenthaler turned to the use of acrylic rather than oil in the early 1960s, which she found to be “not as involved in métier, wrist or medium as is often the case with oil. At its best, it fights painterliness for me… Moreover, her turn to using acrylic was part of a ‘struggle for me to both discard and retain what is gestural and personal’” (John Elderfield, ibid., p. 166).

U-Turn dates from this consequential period of Frankenthaler’s work, when she had fully succeeded in independently forging her own aesthetic that was neither Color Field nor Abstract Expressionism. The late 1960s were a time of critical acclaim for Frankenthaler when the Whitney Museum of American Art organized her first retrospective in 1969 and renowned curator Henry Geldzahler selected her as the sole female artist in his seminal survey exhibition of New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her unique and deeply instinctive gift for coloration was fully recognized in the 1960s, and continued throughout her long career and into the 21st century.