- 26

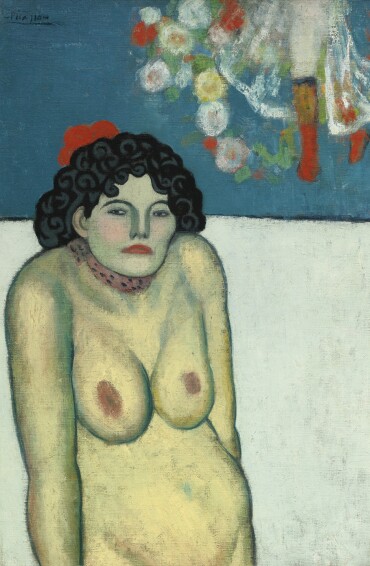

巴布羅·畢加索

描述

- 巴布羅·畢加索

- 《浮誇的女人》

- 款識:畫家簽名 Picasso(左上);背面另畫有整幅畫並題款 Recuerdo a Mañach en el día de su santo

- 油彩畫布

- 31 7/8 x 21 1/4 英寸

- 81.3 x 54 公分

來源

Demotte Gallery, New York (1931)

Josef von Sternberg, Hollywood (acquired from the above before 1935 and sold: Parke Bernet Galleries, New York, November 22, 1949, lot 89)

Perls Gallery, New York (acquired at the above sale)

Jacques Sarlie, New York (sold: Sotheby’s, London, October 12, 1960, lot 5)

Galerie Alex Maguy, Paris (acquired at the above sale)

Private Collection (sale: Sotheby’s, London, December 4, 1984, lot 23 )

Acquired at the above sale

展覽

Los Angeles County Museum, 1935

Los Angeles County Museum, The Collection of Josef von Sternberg, 1943, no. 40, illustrated in the catalogue

The Arts Club of Chicago, Exhibition of paintings and drawings from the Josef von Sternberg Collection, 1946, no. 19 (dated circa 1905)

West Palm Beach, The Norton Museum of Art, Picasso: A Vision, 1994

Wichita, Kansas, Wichita Art Museum, A Personal Gathering: Paintings and Sculpture from the Collection of William I. Koch, 1996

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Things I Love: The Many Collections of William I. Koch, 2005 (titled The Night Club Singer)

出版

Fred A. van Braam (ed.), World Collectors Annuary, Delft, 1960, vol. XII, no. 4187

Pierre Daix & Georges Boudaille, Picasso 1900-1906, Catalogue Raisonné de l’oeuvre peint, Paris, 1966, no. VI. 18, illustrated p. 198

Alberto Moravia & Paolo Lecaldano, Picasso blu e rosa, Milan, 1968, no. 7, illustrated p. 88 (titled Nudo stanco)

Josep Palau i Fabre, Picasso. The Early Years 1881-1907, New York, 1981, no. 661, illustrated p. 263 (titled Nudity)

Pierre Daix, Picasso. Life and Art, New York, 1993, mentioned p. 30

Pierre Daix, Dictionnaire Picasso, Paris, 1995, mentioned p. 402

Michelle Falkenstein, “Picasso’s Double Vision,” in Art News, New York, January 1, 2005

The Picasso Project, ed., Picasso’s Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings and Sculpture, Turn of the Century, 1900-1901, San Francisco, 2010, no. 1901-410, illustrated p. 233

Becoming Picasso. Paris 1901 (exhibition catalogue), The Courtauld Gallery, London, 2013, illustrated in color p. 49

拍品資料及來源

In recent correspondence with Sotheby's, curator and Picasso historian Marilyn McCully has provided her interpretation of the picture, in which she states that it features an entertainer posed in front of a painting in Picasso's studio. Art historians have also suggested that the composition depicts a cabaret perform in front of a stage, where a dancer appears to be swirling a floral skirt. McCully has expanded on her analysis as follows:

"The painting known as La Gommeuse represents a pivotal moment in Picasso’s artistic development in 1901, the year in which he had his first major exhibition at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery in Paris (24 June-14 July 1901). That show had featured more than sixty paintings and drawings, which reflected the young Spaniard’s immediate response to recent French art. The major influence was Toulouse Lautrec, both in subject matter – café scenes, prostitutes and dance halls – and, to some extent, technique, but Picasso’s subsequent focus on isolated figures and restricted, subdued palettes in his new works emphasized his own exploration of the theme of loneliness and his interest in formal experimentation. The depictions of syphilitic prostitutes and poverty-stricken mothers in his Blue Period of late 1901-1902 was in many ways anticipated in La Gommeuse and works related to it.

Here the nude, who is placed at the left in the foreground, is enclosed with a strong defining outline to emphasize her self-containment within the composition. Her body, with its ochre and greenish hues, is set against a flat background divided between light and dark, in a way that is reminiscent of a similar formal device used by Gauguin to give emphasis to frontal figures. The slumped position of La Gommeuse, where her head obscures her neck and joins her rounded shoulders, is characteristic of a group of compositions by Picasso in which women, usually seated at café tables, are depicted alone. These “sisters” of La Gommeuse, painted from the late summer to the autumn of 1901– such as Woman with a chignon (Fogg Art Museum) – are, however, always dressed. And while these women often seem to have been of a generic, French type, La Gommeuse appears to have been based on a specific model. The woman’s black wavy hair, black curved eyebrows, straight nose, and downturned mouth are noticeably different from the others, whose red or dark hair is piled on their heads.

The title La Gommeuse was probably given to this composition when it was exhibited, and the woman portrayed was presumably an entertainer. Around 1900 the word ‘gommeuse’ was popularly associated with sexily dressed – or underdressed – café-concert singers and with their songs. We know that in 1901 Picasso drew from life a number of such performers, including the celebrated singer Polaire, for the Paris journal Frou Frou, which published his drawings between February and September 1901. Polaire, who is easily identified by her wavy black hair and diminutive features and often wore plunging necklines and even patterned scarves around her neck, may have been the inspiration if not the real model for this composition. Around the turn of the century, when Polaire was performing in Paris, she was referred to as “la gommeuse épileptique” because of the way her body shook as she shifted her feet from one side to the other during her songs.

Picasso painted La Gommeuse in his atelier on the Boulevard de Clichy, and the painting on the wall behind the figure defines the setting as the artist’s studio, where the woman may actually have posed. In the painting on the wall we only see the lower part of what appears to be a large, predominantly blue canvas with a figure wearing a gauzy dress and red stockings, surrounded by loosely painted, bright colors – evoking another composition that Picasso had done earlier in the summer of 1901, Nude with red stockings (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyons).

The caricatural composition on the reverse of La Gommeuse bears the inscription “Recuerdo a Mañach en el día de su santo” – which reveals that the canvas was intended as a gift to Pere Mañach on his Saint’s Day (29 June), and this allows the completion of the canvas to be dated with accuracy. Pere Mañach, who shared the Boulevard de Clichy studio with the artist, was a Catalan who lived in Paris and worked as a runner for several dealers, scouting out new artists from Spain. He had been responsible for finding buyers for Picasso’s works in 1900 and had put him under contract when the artist returned to his native country at the end of that year. It was Mañach who organized for the artist to show at Vollard’s in the following summer, and Picasso’s bold portrait of his friend (National Gallery of Art, Washington) was one of the featured works in the Vollard show.

In contrast to the rather conventional pose of Picasso’s formal portrait of Mañach, the painting on the reverse of La Gommeuse shows the moustached dealer wearing a turban, which is painted with yellow and red stripes, perhaps alluding to the Catalan flag. Mañach’s nude body is adorned with necklaces, and the awkward posture suggests that he has assumed a sexual, if not Kamasutra-like pose. Picasso shows him urinating in an imaginary landscape, which is dotted with lotus flowers and unexplained symbols. If, as we assume from the inscription, La Gommeuse was a gift to Mañach on 29 June 1901, the latter must have sold or given the canvas to Vollard at a later date" (Marilyn McCully, "La Gommeuse," in correspondence with Sotheby's, October 2015).

Picasso's emasculation of Mañach here is not without significance, evidencing the whimsical spirit of the young Spaniard at a particularly vulnerable moment of his life. Picasso's reasons for poking fun at Mañach's are not made explicit, but his outrageously wicked rendering of the man speaks volumes about the ribald exchanges that must have transpired between them. Perhaps it is no surprise that Mañach did not retain this picture and it ended up with the more successful dealer Ambroise Vollard, probably sometime after 1906. In later years, it came into the possession of the young New York dealer Lucien Demotte, who sold it to Josef von Sternberg (1894-1949), one of the most acclaimed Hollywood film directors of the 1930s. Sternberg is best remembered as the director of the 1930 film "The Blue Angel," in which Marlene Dietrich made her screen debut as the louche caberet performer Lola Lola. It seems that Sternberg acquired this work about one year after the release of "The Blue Angel," so the subject of La Gommeuse would have held great significance for the director. In 1949 Sternberg sold this picture, along with over one hundred other objects from his collection of fine art, at Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York. It was later acquired by Jacques Sarlie, a Dutch-born financier based in New York, who had befriended Picasso after the war and amassed a large collection of the artist's work from every period. Sarlie sold this picture at Sotheby's in London in 1960, at which point it was acquired by a dealer for a private collection. The picture was later offered for sale at Sotheby's in 1984, when it was purchased by William I. Koch, who has kept it in his private collection for the last 30 years.

Having lived with this picture for three decades, Mr. Koch has interpreted La Gommeuse to be slumped on a banquette or divan in the same fatigued posture of so many of Degas' ballet dancers post-performance. Her sad, contemplative expression and physical exhaustion inspire the viewer to think about what her life must have been like that evening. The verso of the picture, however, presents a whimsical character depicting Manach’s head on a woman’s body leaping like a dancer. The paradoxes presented by this dual composition will no doubt continue to intrigue generations to come.

Sotheby's would like to thank Marilyn McCully for contributing to the catalogue essay of the present lot.