S

otheby’s is honored to present over 300 Chinese works of art and paintings spanning from the Shang dynasty to the Republic period. Highlights include an exceptionally rare and impressive Warring States period gold, silver and glass-embellished bronze vessel formerly in the collection of Adolphe (1871-1949) and Suzanne (1874-1949) Stoclet, a rare Qianlong seal mark and period underglaze-blue and copper-red bottle vase, a group of early Buddhist gilt-bronze figures from a Japanese private collection, jade and hardstone carvings from the collection of William Boyce Thompson (1869-1930), Ming dynasty blue and white porcelains from a distinguished New York private collection, ceramics and works of art from the Hauge Collection, and a handscroll by Li Shan.

Select Highlights

An Ancient Vessel Forged from Fires of the Warring States

Lot 578 | AN EXCEPTIONALLY RARE AND IMPORTANT GOLD, SILVER AND GLASS-EMBELLISHED BRONZE VESSEL (FANG HU)

WARRING STATES PERIOD, 4TH / 3RD CENTURY BC

ESTIMATE $2,500,000- 3,500,000

VIEW LOT

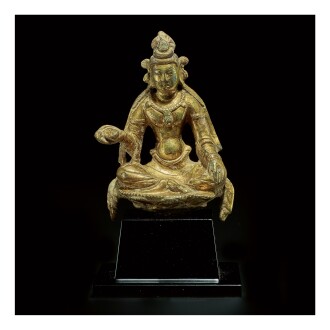

A ssembled over many years by a discerning Japanese private collector, the gilt-bronze figures in this group are notable for their rarity, quality of workmanship, and thematic unity. Broadly, the group reflects the evolution of Chinese Buddhist figural art from the 4th to 10th centuries, beginning with the elemental forms of the Sixteen Kingdoms and Northern Wei dynasty, transitioning to the sinuous figures of the Sui dynasty characterized by dynamic poses and rich ornamentation, and culminating in the fleshy, sculptural bodies of the Tang and Liao dynasties when artisans and patrons expanded the range of Buddhist subjects represented in art. Amongst these Buddhist devotional works are a few particularly rare gilt-bronze figures of secular and Daoist figures, offering insight into both religious and nonspiritual practices of medieval China.

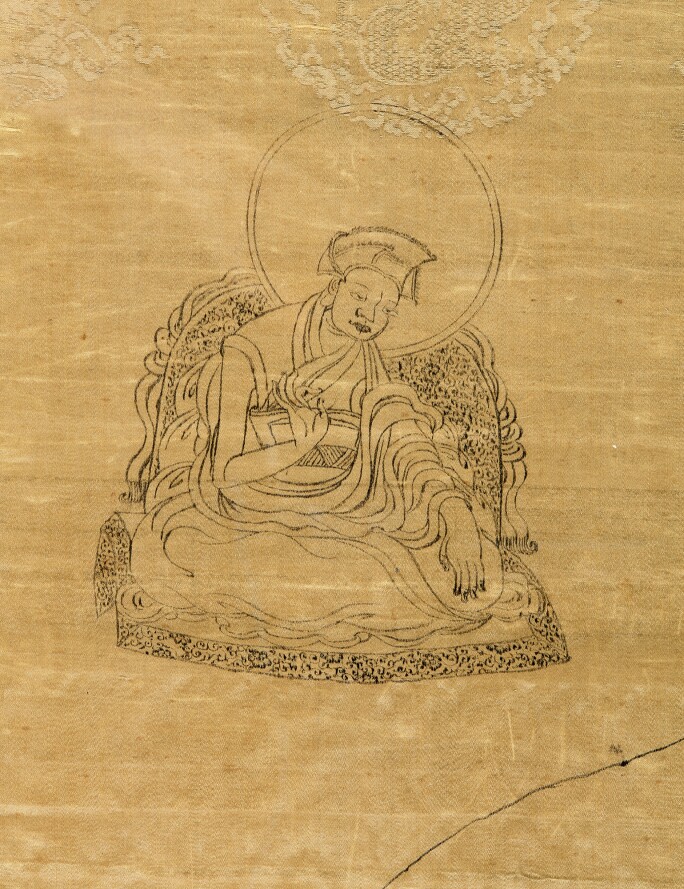

F rom the 17th century onwards, important edicts, proclamations, and letters within the Tibeto-Mongolic world were often handwritten on silk in ornate presentations. These official documents, like other diplomatic and legal documents written on paper, were authenticated by means of seal impressions. The present document is a bilingual travel permit issued by the Seventh Dalai Lama, Kelzang Gyatso (1708-1757), identified by the impression of his seal, which was bestowed by the Yongzheng Emperor.

This travel permit was granted to a monk named Ta Lama Lodro Khechok from the Lower Tantric College of Gyume in Lhasa. He was appointed by the Dalai Lama to travel to Mongolia to oversee ritual services that maintained the stability of the Qing empire. The permit is addressed to the leaders and officials of different Mongol tribes to guarantee protection and ensure assistance to the bearer. The final part of the document provides the date and place of issuance, which are consistent with the records on the exile of the Seventh Dalai Lama to Eastern Tibet where he was to stay until 1736. According to Tibetan sources, the Seventh Dalai Lama arrived in Litang and Gartar from Chamdo on the 8th day of the 2nd month of the Earth-Bird year, where he was welcomed by a large crowd of clerics, religious dignitaries, and local officials. Thus, the travel permit was issued from the Kham monastery of Ganden Thubchen Jampa Ling at Litang, rather than from Lhasa as might be otherwise expected. Explore the various elements of this important document below:

Depiction of Tsongkhapa (1357–1419)

Depiction of the Fourth Panchen Lama Lobsang Chökyi Gyeltsen (1570–1662)

Depiction of the First Dalai Lama Gedun Drup (1391–1474)

Depiction of Yama Dharmarāja and his consort

Cāmuṇḍa

Depiction of Six-armed Mahākāla

Depiction of Śrimatī Pārvati Rājñī

Impression of the gold seal bestowed by the Yongzheng emperor (r. 1723-1735) to the Seventh Dalai Lama, Kelzang Gyatso (1708-1757). The quadrilingual seal face translates to ‘Seal of the Dalai Lama, the All-knowing Vajradhara, the Victorious One over the highest pure realms in the west, Holder of the complete teaching of the Buddha on earth’.

Impression of the gyatam seal in phags-pa script. A gyatam seal is generally found at the end of the title in Tibetan diplomatic and legal documents.

The main text: this section indicates the permit was granted to a monk named Ta Lama Lodro Khechok, who was appointed by the Dalai Lama to travel to Mongolia to oversee ritual services for the longevity of the Qing emperor.

The introduction: this title section identifies that the present travel permit was issued by the Dalai Lama under the authority of the Qing emperor.

The final protocol: this section concludes the document with a date and place of issuance. It states that the permit was written in the Earth-Bird Year (1729) at Ganden Thubchen Jampa Ling, Litang.

The elegant calligraphic handwriting on the present document is a type of Tibetan cursive script called drutsa.

Empire of Great Brightness. Imperial Arts of the Ming Dynasty

200 Years of Ming Blue and White from a Distinguished New York Private Collection

A collection of seven blue and white wares from the Ming dynasty document the development of blue and white porcelain over the course of 200 years, bookended by exemplary porcelains from two prolifically innovative yet politically unstable periods. Lot 513, a blue and white meiping from the mid-15th century, was produced during the Interregnum Period (1436-1464), which lasted twenty-eight years following the Tumu Crisis. Due to the political discord and associated economic strain, porcelains produced during this era do not bear imperial reign marks. Lots 514-518 from the reigns of the Jiajing (1522-1566) and Wanli (1573-1620) emperors, represent the start of the late Ming period and are decorated with popular imagery of the time—including Daoist themes and children at play. Finally, lot 519 demonstrates the new style of painting and adaptation of narrative subjects during the Transitional Period, circa 1640, in the final years of the Chongzhen Emperor’s reign (1628-1644). The collapse of the Ming dynasty in the second quarter of the 17th century led to the cessation of court commissions for porcelain, forcing porcelain manufacturers to find alternative audiences for their wares and cater to the tastes of the new clientele.

Power & Glory: Court Arts of the Qing Dynasty

I

nscriptions have played a unique role in Chinese ritual and creative practices. Appearing on almost all mediums, including bone, bronze, and jade, these artistic scripts of various forms and styles were essential to the development of Chinese calligraphy and have long been admired and studied. They encapsulate the generations of wisdom and are an integral part of China’s cultural identity.

- Shang Dynasty

- Western Zhou Dynasty

- Northern Wei Dynasty

- Sui/Tang Dynasty

- Ming Dynasty

- Qing Dynasty

- Republic Period

-

Shang DynastyA RARE GROUP OF ELEVEN ORACLE BONES WITH INSCRIPTIONS, SHANG DYNASTY, 13TH-11TH CENTURY BC

Shang DynastyA RARE GROUP OF ELEVEN ORACLE BONES WITH INSCRIPTIONS, SHANG DYNASTY, 13TH-11TH CENTURY BC

LOT SOLD $44,100

The oracle bone inscriptions, jiaguwen, which literally translate to ‘writings on shells and bones’, are the earliest surviving writing systems in China. These ancient inscriptions consist mostly of pictographic characters. Their contents are usually related to divination, including on the topics of hunting, warfare, weather and fortunes. The oracle bone inscriptions were especially popular during the late Shang period, but were discontinued after the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BC). -

Western Zhou DynastyAN IMPORTANT ARCHAIC BRONZE RITUAL FOOD VESSEL (GUI), WESTERN ZHOU DYNASTY

Western Zhou DynastyAN IMPORTANT ARCHAIC BRONZE RITUAL FOOD VESSEL (GUI), WESTERN ZHOU DYNASTY

LOT SOLD $478,800

The inscriptions on archaic bronzes are commonly known in Chinese as jinwen (gold inscriptions) or zhongdingwen (bells and ding inscriptions). These inscriptions range from a single pictogram to hundreds of characters, and coexisted with oracle bone inscriptions during the Shang and Zhou dynasties and gradually declined in popularity after the introduction of xiaozhuan (small seal script), a standardized writing script promulgated by Qin Shi Huang (259-210 BC). -

Northern Wei DynastyA GILT-BRONZE FIGURE OF A SEATED BUDDHA, NORTHERN WEI DYNASTY, DATED TAIHE SECOND YEAR, CORRESPONDING TO 478

Northern Wei DynastyA GILT-BRONZE FIGURE OF A SEATED BUDDHA, NORTHERN WEI DYNASTY, DATED TAIHE SECOND YEAR, CORRESPONDING TO 478

LOT SOLD $252,000

Inscriptions on Buddhist sculptures record votive dedications. As a means to accumulate merit, these inscriptions are often dated and cite the names of the patrons and devotees. The inscriptions are usually in kaishu (regular script), which was developed between the Eastern Han (25-220) and Six Dynasties (222-589) and has remained as a standard writing script in China to the present day. -

Sui/Tang DynastyAN INSCRIBED SILVERED 'BAOXIANGHUA' MIRROR, SUI / TANG DYNASTY

Sui/Tang DynastyAN INSCRIBED SILVERED 'BAOXIANGHUA' MIRROR, SUI / TANG DYNASTY

ESTIMATE $40,000-60,000

The inclusion of inscriptions alongside decorative designs on bronze mirrors emerged during the Han dynasty (220 BC-206 AD). This tradition continued in the subsequent dynasties. The inscriptions on the mirrors of the Sui (581-618) and Tang dynasties (618-907) are often auspicious phrases, poems, and eulogies. -

Ming DynastyAN EXTREMELY RARE CARVED GREY JADE FIGURE OF ZHENWU, MING DYNASTY, HONGZHI PERIOD, DATED TO THE EIGHTH YEAR, CORRESPONDING TO 1495

Ming DynastyAN EXTREMELY RARE CARVED GREY JADE FIGURE OF ZHENWU, MING DYNASTY, HONGZHI PERIOD, DATED TO THE EIGHTH YEAR, CORRESPONDING TO 1495

ESTIMATE $300,000-500,000

Inscriptions on Ming dynasty jade carvings of Daoist figures are rare. The inscription on the back of this jade Zhenwu figure contains a date, 8th year of Hongzhi (1495), and a name, Zhu Yuan, who could be the patron of this figure. -

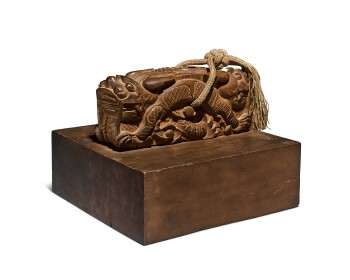

Qing DynastyAN EXCEPTIONALLY RARE IMPERIAL TANXIANGMU SEAL, LATE QING DYNASTY

Qing DynastyAN EXCEPTIONALLY RARE IMPERIAL TANXIANGMU SEAL, LATE QING DYNASTY

LOT SOLD $81,900

Poetic verses from classical Chinese literature were particularly favored by Qing rulers, who often commissioned their incorporation into imperial seals. The present seal bears a four-character inscription in seal script reading Xieci yuanchun, which can be interpreted as ‘in celebration of the New Year’. It is a verse from a poem recorded in the Chinese classic Yuefu shiji [Collection of Yuefu poetry] which was recited on a New Year banquet during the Sui dynasty (581-618). -

Republic PeriodA PAIR OF FAMILLE-ROSE 'FIGURAL' PLAQUES BY WANG QI, REPUBLIC PERIOD, DATED JISI YEAR, CORRESPONDING TO 1929

Republic PeriodA PAIR OF FAMILLE-ROSE 'FIGURAL' PLAQUES BY WANG QI, REPUBLIC PERIOD, DATED JISI YEAR, CORRESPONDING TO 1929

LOT SOLD $239,400

Following closely the tradition of Chinese painting, the inclusion of inscriptions on porcelain plaques became an established practice during the Republic period (1912-1949). Apart from being a display of calligraphy, these accompanying writings also provide insight into the context in which a painting was created.

S otheby’s is honored to present a selection of works acquired by brothers Victor (1919-2013) and Osborne (1914-2004) Hauge, who were stationed in Tokyo with the U.S. Department of State in the 1940s. Advised by noted ceramics scholar Fujio Koyama (1900-1975), and buying from the leading Japanese firm, Mayuyama & Co., in Tokyo, the brothers collected works that reflected traditional Japanese aesthetics and appreciation for Chinese art.

Over the course of fifty years, Victor and Osborne, together with their wives Takako (1923-2015) and Gratia (1907-2000), took advantage of their international posting and travels to immerse themselves in Asian and Near Eastern art. Together, the two couples amassed an extraordinary and celebrated collection of Southeast Asian, Chinese, Japanese, Near Eastern and Persian ceramics.

Since 1996, the Hauges jointly gave three remarkable gifts of Asian art to the Freer and Sackler Galleries (now the National Museum of Asian Art) in Washington D.C., starting with their collection of Khmer ceramics in 1996, the Near Eastern and Persian ceramics in 2000, and a group of 550 Asian ceramics in 2006. Celebrations of these gifts culminated in the exhibitions Taking Shape and Asian Traditions in Clay held at the Museum. Other works from the Hauge Collection now in prominent museum collections include a Tang dynasty Tianlongshan bodhisattva in the Cleveland Museum of Art, which was also acquired from Mayuyama & Co. in Tokyo.

W

illiam Boyce Thompson (1869-1930) was an influential mining baron, financier, political insider, and philanthropist during the turn of the 20th century. Believing that sustainable agriculture and food supply were critical for global stability and human welfare, he established the Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research in Yonkers, New York, which continues to make major contributions in the field. Thompson’s lifelong interest in the natural world led him to amass a fine collection of carved gems and stones, a portion of which was willed to the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The present selection of Chinese carvings in jade, jadeite, rock crystal, lapis lazuli, amethyst, and agate reveal Thompson’s aesthetic taste and attention to material quality, and have remained in the family for almost 100 years.

Above image: William Boyce Thompson, Courtesy of Boyce Thompson Arboretum

L i Shan is best known as one of an important group of painters who were later dubbed the 'Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou' due to their expressive and bold style of painting. He was born in Xinghua, Jiangsu province to a prominent scholar-official family. From an early age, Li studied poetry, calligraphy, and painting from a number of different masters and he achieved early success, passing the second level examinations at the age of twenty five. He gained entry into the Imperial Study where he had the great fortune to be tutored in painting by the famed scholar-official Jiang Tingxi (1669-1732). Jiang was known for his paintings of birds and flowers, which he produced in two distinct styles—one a more calligraphic, sketchy mode in ink on paper, and the other a finely drawn, meticulously colored manner, generally on silk. Li Shan presumably learned both techniques from Jiang Tingxi. He later studied with Gao Qipei (1660-1734), an artist renowned for his finger paintings done in a highly impressionistic style.

Li Shan is best known for his works from the latter period, which tend to be large-scale, powerful but simple compositions on paper rendered with broad, energetic brushstrokes and copious amounts of ink. This style presumably appealed to the salt merchants and other wealthy clientele of 18th century Yangzhou, an important commercial center.

T he Song dynasty (960-1279) was a period of tremendous production and innovation for Chinese ceramics. During this time, many kilns became famous for producing wares with particular aesthetic and technical characteristics, which led to both local specialization as well as the imitation of these novel techniques at competitors’ studios farther afield. Such experimentation and borrowing increased the diversity and quality of ceramic wares, thereby allowing potters to satisfy the desires of clients ranging from the imperial household, to scholar-elites, to merchants who serviced both domestic and international markets. The present sale showcases the range of ceramics produced during the period, with special attention to monochrome glazes, abstract designs created through contrasting colors, and the use of carving as a decorative method.

P opular dramas and tales of virtue were favorite subject matters for Chinese artists and artisans. Drawn from classics of Chinese literature, such as the Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Romance of the Western Chamber, and historical accounts, such as the story of Jiang Ziya and Guo Ziyi, these narrative scenes are recorded on the surfaces of numerous works of art. To this day, these depictions are as familiar to collectors and connoisseurs as they would have been centuries ago when they were made. Discover the scenes below: