T uyet Nguyet (1934-2020) and Stephen Markbreiter (1921-2014) were passionate collectors of Asian Art, over the years amassing a comprehensive collection that includes a diverse range of arts from different cultures. Following the earlier successful sales of gilt-bronze Buddhist metalwork, jade carvings, China trade paintings, and snuff bottles, this online auction presents a remarkable assemblage of antique gold jewellery. Among Tuyet Nguyet's many passions was her antique jewellery collection which represents pieces she acquired over a span of 40 years with an eye toward the finest examples from Java, Khmer, Burma, Vietnam and Tibet. The sale also features the most remarkable group of gold rings from the Angkor period, 9th century, their superb workmanship and sumptuousness indicating they were made for the royal court.

Featured Highlights

Mapping of the History of Asian Gold Jewellery

Khmer – A Testament of Power

The Khmer empire was a mighty state in Southeast Asia that flourished from the 9th to 15th centuries. At its peak, it controlled present-day Cambodia and large areas of Vietnam, Thailand, and Laos.

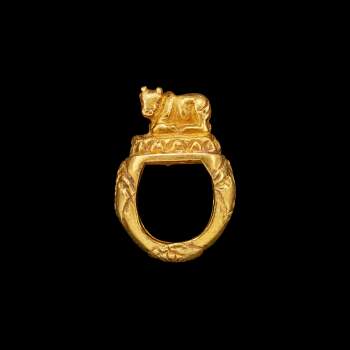

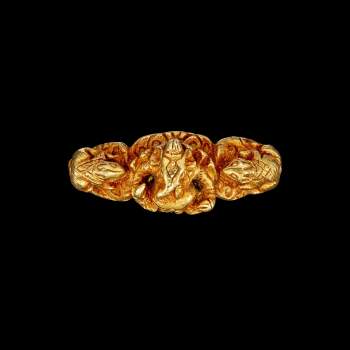

Before and during the Khmer empire, the region was heavily influenced by India. In the later 8th century, the Javanese conquered part of the Pre-Angkorian empire, which greatly influenced the style of ornamentation found in the Angkor period. As a result, the Hindu-Buddhist iconography became prominent, as seen in a group of gold rings in the collection.

The most remarkable group of rings in this collection come from the Angkor period. These rings can be stylistically identified by the architectural features mirrored in the goldwork, reminiscent of details found on the friezes of the Angkor Wat temple complex. Their superb craftsmanship and sumptuousness suggests the rings were made for the royal court.

Java – A Convergence of Islamic Culture

Jewellery has been the most prevalent form of ancient goldware across Southeast Asia, of which the most impressive traces of Indonesian civilisation are from Java. The Tuyet Nguyet and Stephen Markbreiter Collection includes a significant portion of gold jewellery from this region dating from the 7th to early 16th century, a period also known as the Classical Period, illustrating Javanese goldsmiths' copious variety and intricate artistry.

The Classical Period is conventionally divided into three phases: Early Classical Period (7th - 9th century), where the political power was based in Central Java; Middle Classical Period (10th - mid 13th century), where the authority shifted to East Java; and Late Classical Period (mid 13th - early 16th century), which is characterised by the Majapahit Empire - one of the greatest of the early Indonesian kingdoms. The Majapahit Empire came to its demise in 1519 with the arrival of Islam, signalling the end of the Classical Period as a whole.

During this period, Javanese goldsmiths were highly esteemed in society, listed among the five main crafts. They produced some of the most unique and intricate gold jewellery, particularly rings. Their skill was highly advanced, creating designs that significantly diverged from their Southeast Asian counterparts, such as rings with auspicious motifs, wire-wrapped rings, rings associated with Hindu-Buddhist iconography, and ear clips.

Pyu

In the 8th century, the eastern region of modern-day Myanmar was ruled by the Pyu people, who struck coins with designs inspired by the Arakanese kingdom to the west, such as lot 1061.

The front of the coin depicts a throne adorned with royal diadems; the reverse features the Shrivastava emblem, which represents Sri, the goddess of wealth and prosperity. Within the Shrivastava emblem, a mountain representing the earth and also Shiva, the god of opposing forces, rises from the primordial water below and under the heavens signified by the moon and sun above. The mountain is flanked by a vajra thunderbolt, an emblem of Indra, the god of the heavens, and a shankha conch shell, a symbol associated with Vishnu, the god of creation and preserver of the cosmic system.

The bail suggests it may have also been used as an amulet. The production of coinage largely ceased in the 9th century with the demise of the Pyu. Although Pyu coins were highly standardized in size and weight, it is uncertain if they were used as currency in the contemporary sense or as royally sanctioned bullion due to their scarcity.

Indonesian Archipelago – The Sumbanese Mamuli

The Sumbanese believed precious metals had a celestial origin. The sun is made of gold, while the moon and stars are of silver. Gold and silver are deposited on Earth when the sun and moon set or shooting stars fall from the sky. Sumbanese regarded ornaments made of gold as a symbol of divine favour. They would commission gold jewellery to be used as ancestral heirlooms, and to ascend the social ladder by displaying these heavenly treasures at celebrations.

Mamuli, usually made of gold or silver, are among the most important ornaments typically used in the exchange of gifts associated with marriages and alliances. They were worn as ear ornaments when the Sumbanese practised artificial earlobe extension, but they could also be worn as neck pendants.

Mamuli also embodied Sumbanese's dualistic belief in cosmology: heaven and earth, male and female. It takes after the shape of omega (Ω), a fertility symbol representing female genitalia; the animals at the base represent the male aspect. In lot 1027, we have two whimsical monkeys, skilfully constructed with rotatable bodies, movable heads and arms. While in lot 1070, we have water buffaloes and Sumba-native cockatoos.

Sumbanese's mamuli has become so well-known that the omega form is often referred to by its Sumbanese name mamuli across Indonesia.

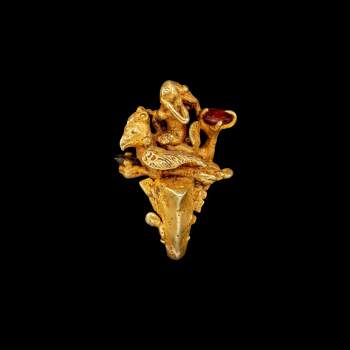

India – A Burst of Colours

In the late 16th century, Mughal court goldsmiths ingeniously combined enamelling with the kundan setting technique. This sophisticated art form came to India during the Mughal invasion and has been practised in India ever since. Such lavish ornamentation is evident in a kada bangle and a 'bird' ring in this collection.

In India, the art of enamelling is known as meenakari. The word 'meenakari' means to place paradise onto an object. Jaipur artisans perfected this art form and developed their distinctive style. It is defined by the vivid red colour and the intricate designs enamelled on the back or inner surfaces of ornaments. The enamelled details remain unseen, adding hidden interest that only the wearer knew about.

In lot 1023, the inner surface of the kada bangle is exquisitely decorated with pairs of peacocks enamelled in vibrant shades of blue and green, against a floral design picked out in vivid red. While the reverse of the 'bird' ring (lot 1019) enamelled with a peacock in green, white, red and blue, echoing the front design and choice of gems – emerald, diamond and ruby.

These two pieces reveal that meenakari work requires a great deal of attention and precision. The craftsmen have to first engrave a complex design onto a small surface area, chisel off the grooves before filling in the tiny spaces with enamels. Meenakari adds greater artistic value to the piece and has a pragmatic reason behind it. It protects the high-karat gold from abrasion due to frequent skin contact, and gives the jewellery piece the rigidity necessary to keep its form.

Another known characteristic of Indian jewellery is the kundan setting technique. It is a process of setting gemstones with thin sheets of pure gold, or kundan. This sophisticated technique allows precious stones of any size or shape to be set directly into fragile enamelled surfaces.

Indian jewellery is renowned for the luxuriance of their artefacts, combined with designs of great complexity. They, such as the kada bangle, were considered objects of marvel; they were brought overseas and displayed in London at the Great International Exhibitions in the 1850s.

For a similar bangle, see one with a blue-enamelled ground, in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection, accession no. 119-1852 (https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O68463/jewellery-unknown/).