Old Master & 19th Century Paintings Evening Auction

Old Master & 19th Century Paintings Evening Auction

The Property of a Distinguished Private Collector

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn

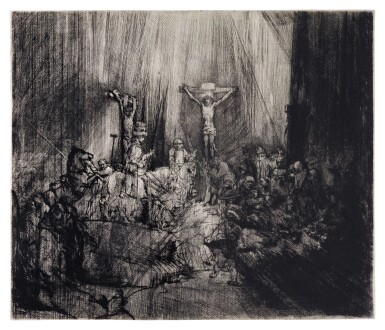

Christ Crucified between the two Thieves: 'The Three Crosses'

Auction Closed

December 4, 07:09 PM GMT

Estimate

400,000 - 600,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

The Property of a Distinguished Private Collector

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn

Leiden 1606–1669 Amsterdam

Christ Crucified between the two Thieves: 'The Three Crosses'

drypoint, 1653, a fine impression of New Hollstein's fourth state (of five), displaying remarkable tonal warmth, clarity and legibility, while printing with rich burr and dramatic chiaroscuro, on laid paper

sheet: 389 x 457 mm.; 15¼ x 17⅞ in.

With a partial, faded inscription verso (probably Paul Davidsohn, London, Vienna and Berlin, cf. L. 654)

Carl and Rose Hirschler, Amsterdam and Haarlem (L. 633a)

C. White and K.G. Boon, Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts, Amsterdam 1969, vol. XVIII, pp. 43–44, no. 78 (other impressions illustrated);

E. Hinterding, G. Luijten and M. Royalton-Kisch, Rembrandt the Printmaker, London 2000, pp. 297-300, no. 73 (other impressions illustrated);

E. Hinterding and J. Rutgers, The New Hollstein, Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts: 1450–1700, Ouderkerk aan den Ijssel 2013, vol. II, pp. 222–24, no. 274 (other impressions illustrated).

You May Also Like