Native American Art

Native American Art

Property from an American Private Collection

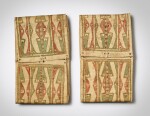

Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne) Pair of Painted Hide Parfleche Envelopes

Lot Closed

January 19, 08:11 PM GMT

Estimate

100,000 - 150,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from an American Private Collection

Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne) Pair of Painted Hide Parfleche Envelopes

Length: 24 ½ (62.2 cm) and 24 in (61 cm); width (both): 14 ¼ in (36.2 cm)

The reverse of one bag inscribed in pencil: "H.J.S." and "Comanche"

Reportedly collected in 1905

Herbert J. Spinden, New York, acquired by 1939

George Terasaki, New York

Evan M. Maurer, Minneapolis, acquired from the above

Sotheby’s, New York, May 20, 2009, lot 37, consigned by the above

American Private Collection, acquired at the above auction

John Canfield Ewers, Plains Indian Painting: A Description of an Aboriginal American Art, Stanford, California, 1939, pl. 30b

Frederic H. Douglas and René d’Harnoncourt, Indian Art of the United States, New York, 1941, p. 144, fig. 61

Miguel Covarrubias, The Eagle, the Jaguar, and the Serpent: Indian Art of the Americas. North America: Alaska, Canada, The United States, New York, 1954, p. XLVIII

Gaylord Torrence, The American Indian Parfleche: A Tradition of Abstract Painting, Seattle and Des Moines, 1994, p. 111, fig. 25

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Indian Art of the United States, January 22 – April 27, 1941

The Brooklyn Museum, New York, long-term loan, circa 1954 (exact dates unknown)

The Des Moines Art Center, The American Indian Parfleche: A Tradition of Abstract Painting, May 28 – August 7, 1994

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, long-term loan, May 2015 – August 2017 (inv. no. L.2015.31.9a,b)

"The exceptional quality of Cheyenne artistic traditions is widely recognized and is clearly visible in the technical excellence and unsurpassed elegance of their parfleches. Among the Cheyenne, artistic expression was a manifestation of religious belief, and the creation of various art forms was directed and strictly maintained by guilds comprised of elected women recognized for their skill, character and spiritual knowledge.

The distinctive character of Cheyenne parfleches emerges from the power of the drawing. The images possess a sense of tension and precise linear structure deriving from the artists' emphasis on fine, brown-black outlining, which is the primary activating element of the paintings. This effect of line is frequently enhanced by the placement of small black units throughout the design; these units - which might include triangles, hourglasses, diamonds, short lines, squares, circles and distinctive ball-tipped finials - establish shifting focal points and rhythmic directional movements. They also dramatically extend the complexity and scale of elements comprising the image. These units are integrated within the order of larger colored forms through the linear framework established by the outlining, which also separates painted and unpainted areas and borders all colored shapes.

The refinement and delicacy created by drawing is echoed in other components as well. Compositions are controlled and precisely balanced, with nearly equal amounts of painted and unpainted surface area, creating a subtle, yet active, figure-ground reversal in most designs. The contours of primary forms are often gently curving and rhythmic, yet taut, and seemingly possessed of an inner structure. The use of color is elegant and restrained; usually the paint was relatively transparent resulting in softly luminescent tones that appear imbued with light and space. In addition to various reds and yellows, a range of distinctively pale, beautiful blues and greens were used to create forms that illuminate the rawhide surface and contrast effectively with the black outlining." (Gaylord Torrence, The American Indian Parfleche: A Tradition of Abstract Painting, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994, pp. 105-106).

Commenting on this specific pair, Torrence remarks “Although most parfleches produced during the pre-reservation era were made of bison, elk, and horse hide, others were created from any of the domesticated bovines that came available - cow, bull, steer, or oxen. It’s notable that the earliest documented parfleche, a magnificent Cheyenne envelope collected by Prince Maximilian in 1833 at Fort Pierre, is made from the hide of a domesticated animal. And this is not an isolated example; other Cheyenne cases from the mid-nineteenth century or earlier are known, including the pair of Northern Cheyenne envelopes in the Hirschfield collection. The pigments employed in the painting are of native origin, and the limited palette of green and red, outlined in brownish black is typical of most pre-1850 parfleche containers.” (Gaylord Torrence, personal communication, December 2023).