Important Americana: Furniture, Folk Art, Silver, Chinese Export Art and Prints

Important Americana: Furniture, Folk Art, Silver, Chinese Export Art and Prints

Property from a Private Connecticut Collection

Winfred Rembert (1945-2021)

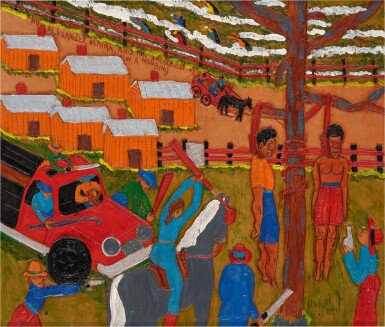

Untitled (Mr. Alexander, Mama, and Me Sneaked Up on a Hanging)

Auction Closed

January 20, 04:11 PM GMT

Estimate

125,000 - 225,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Dye on carved and tooled leather

Executed circa 2011-2015

titled upper left and signed Winfred Rembert lower right, the wheel of the truck incised with the artist’s inmate number in prison 55147 and initials W.R.; the verso with a photo of the artist and his friend, George, the reverse of the photo inscribed Mama, Mr Alexander, and me sneaked upon a lynching on the Sniper farm, I was about six years old, I can’t remember the name of the family, I do know that the Brothers was part of a Big family. Today I wonder what was the reason. – Winfred Rembert

17 1/8 in. by 20 1/8 in. (43.6 by 50.8 cm)

Acquired directly from the artist as a gift by the present owner

It is unimaginable for the majority of us living today to witness a lynching like Winfred Rembert did at the age of six; with corpses hanging from a tree in broad daylight near neighbors’ homes and workplaces. The artist vividly recollects and portrays this scene in scarring detail, as a regular, everyday occurrence. In the foreground, an angry and armed mob surround the teenage boys hanging lifelessly from the tree; the mob relentless with their weapons still raised amidst no pending threat. The midground contains two rows of shed-like structures, which Rembert called “the projects,” where many of the black plantation workers lived and with three black passengers riding up the road in a mule-drawn wagon in preparation for cutting down the corpses and giving them a proper burial once the mob has dispersed. Meanwhile in the background, black cotton pickers proceed with their daily back-breaking work, undistracted but also likely in fear of spectating. Rembert created very few lynching scenes during his artistic career, as the pain and anguish of these memories made him physically sick to his stomach.

In his Pulitzer Prize award-winning memoir, Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir of the Jim Crow South, Winfred Rembert retells the arduous life of living and working on a plantation. “In 1945, 1950, the owner of the plantation owned the plantation and you too. They still had you in a slavery-like situation. They controlled everybody who lived on that plantation. You couldn’t leave the cotton field because the money you owed was holding you there. The house you lived in was holding you there. Every plantation had a store, where you would get things on credit. The money you owed at the commissary store was holding you there. You just couldn’t get out of that loop, that line of debt. If you picked cotton, you owed money. You could never get out of debt.”[1]

At the age of five or six, as Winfred retells in his memoir, he had his own sack for picking cotton, although his mother was significantly more productive. Easily earning four dollars a day, Winfred's mother picked 200 pounds of cotton by hand from sun-up to sundown. But there was also a sense of community in the cotton fields. “All the people you associate with would get rows beside each other,” states Winfred. “If there was anything good about the cotton field, it was listening to Reverend Alexander and his family sing. I could hear them right now. I could close my eyes right now and hear Reverend Alexander and his family singing church songs in the cotton field. That’s the only good thing I see out of the cotton field- that singing: “Amazing Grace,” “I’m going Home on the Morning Train,” all of those beautiful Southern hymns.”[2]

This story of Reverend Alexander singing in the cotton field is one of many moments where peace and beauty are within places of hell and fury. And likewise, witnessing a lynching alongside the same man he associated as a friend and neighbor is equally confounding. Winfred Rembert’s stories of the Jim Crow South reflect an entanglement of fear, hate, and violence with love, happiness, and community. The tactility of his tooled leather, vibrancy and saturation of his dyes, and the meticulous details and implied sense of movement in his complex compositions evoke the power and convolution of memory and emotions. This highly important picture allows the viewer to see a traumatic scene through the eyes of a young child living in the moment rather than a history book, where facts and accounts have changed and been retold by many over time.

[1] Winfred Rembert as told to Erin I. Kelly, Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir of the Jim Crow South, (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021), p. 23.

[2] Winfred Rembert as told to Erin I. Kelly, Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir of the Jim Crow South, (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021), p. 20.