Arts of the Islamic World and India

Arts of the Islamic World and India

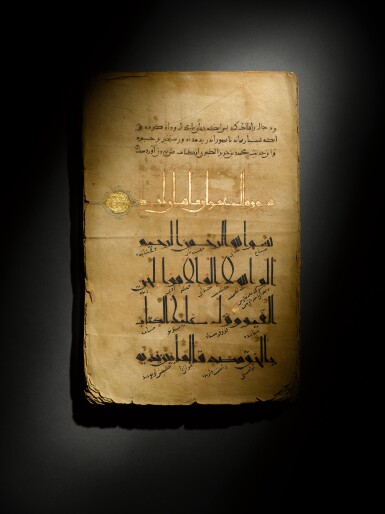

An illuminated Qur’an section in Eastern Kufic script with commentary, Khurasan or Central Asia, Ghaznavid, late 11th/early 12th century

Auction Closed

April 24, 03:45 PM GMT

Estimate

80,000 - 120,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

text: Qur'an, surah Al Imran (III)

Arabic manuscript on paper, 81 leaves, 7 lines per page of bold Eastern Kufic/New Style script, diacritics in red and green (green oxidised to brown), interlinear Persian translation in black naskh, single verse divisions marked with small gold discs in text, fifth verses marked in margins with gold pyriform device containing the word khams, tenth verses marked in margins with gold roundels containing the exact verse count, surah heading of Surah Al Imran written in gold with stylised palmette extending into margin, commentary interspersed within the Quranic text in 19 lines per page in small naskh/new style script

32.2 by 21.5cm.

Sotheby’s, London, 9 April 2008, lot 20

Christie’s, London, 23 April 1996, lot 47

Christie’s, London, 17 October 1995, lot 22

Babaie, Porter & Morris 2017, p. 42

This is a highly important and rare Qur’anic manuscript consisting of the text of surah Al Imran (III) with an accompanying commentary. The Qur’anic text is written in a fine monumental New Style/Eastern Kufic script, in this case NS.I (for the categorisation of the New Style scripts see Déroche 1992, pp.136-7). The script of the commentary consists of a smaller script in the form of an angular naskh or cursive New Style (NS.III). The size, elegant calligraphy and the richness of the illuminated devices for fifth and tenth verse and the gold surah heading and palmette are evidence of the luxury nature of the commission and suggest royal or court patronage.

Early manuscripts of this calligraphic, artistic and codicological sophistication that combine the Qur’anic text with commentary are extremely rare. Only two closely related manuscripts are known, both produced under the patronage of the Ghaznavid dynasty in the late eleventh and early twelfth century, and the present volume is a highly important addition to this small corpus.

Recent research by Alya Karame has revealed and clarified the existence of a rich tradition of Qur’anic manuscript production under the Samanid, Ghaznavid and Ghurid rulers in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries in the eastern Islamic lands, particularly those that employ elegant monumental Eastern Kufic/New Style scripts (Karame 2016). Among these are two Ghaznavid examples that combine the Quranic text and commentary in a similar format to the present volume, with a monumental New Style (NS.I) script for the main Qur’anic text and a smaller script for the commentary. The first is dated 484 AH/1091 AD and was made for the Ghaznavid Sultan Ibrahim (r.1059-99), copied by Uthman ibn Husayn al-Warraq al-Ghaznawi (Topkapi Saray Library, EH.209, see Karame and Zadeh 2015; Karame 2016, vol.1, pp.108-130, vol.2, ch.4, pls.I-XIV). The second is undated but closely related, and may have been copied by the same Uthman as the Topkapi volume (British Library, Or. 6573, see Karame and Zadeh 2015, fig.12; Karame 2016, vol.1, pp.131-3, vol.2, ch.4, pls.XV-XVII). In the Topkapi volume the text of the commentary is a small New Style script, whereas in the British Library copy the commentary script is a small naskh. In the present manuscript the smaller script of the commentary rather cursive New Style and, or angular naskh). All three manuscripts are of a very similar size: the Topkapi volume measures 34 by 24.5cm., the British Library volume measures 33.5 by 26.5cm., and the present volume measures 32.2 by 21.5cm. The only significant difference is that the present volume also features an interlinear Persian translation of the Qur’anic text in a small, neat naskh script positioned diagonally between the lines main lines of Qur’anic text (whereas the Topkapi and British Library volumes do not). We cannot be certain whether this translation was written at the original time of production or was added slightly later. If it is original to the manuscript, it would constitute one of the earliest Persian translations of the Qur’an. It is worth noting that the script of this interlinear translation is very similar to the cursive hand of the commentary script in the British Library volume.

As well as the format, size and calligraphic styles, these three manuscripts are also similar in terms of the scale of the codicological project. The present manuscript consists of 81 leaves and contains the text and commentary of one surah (III, Al Imran). This is one of the longer surahs, consisting of 200 verses with approximately 3,500 words. This equates to around 4.5% of the total text of the Qur’an. Based on this we can estimate that if the original manuscript of which this is one part included the entire Qur’anic text and commentary it would have consisted of approximately 1,800 folios, and must have been bound in many volumes. This was a monumental undertaking, but in this it again relates to the aforementioned Topkapi and British Library volumes. The Topkapi volume contains about a tenth of the Qur’anic text and runs to 239 folios (Karame and Zadeh 2015), suggesting that if the entire text of the Qur’anic and commentary were included it would have consisted of over 2,300 folios. The British Library volume comprises 246 folios and contains the Qur’anic text and associated commentary from surah 18 verse 74 to surah 25 verse 10, consisting of approximately 650 verses and 7340 words. This again equates to around 10% of the Qur’anic text, suggesting a complete version would have run to over 2,400 folios.

The close similarities between these three manuscripts strongly suggests that present volume was also made in the context of Ghaznavid royal or court patronage in the late eleventh or early twelfth century and is a previously unrecognised addition to this rare and significant group. Further research on the commentary text would reveal the specific version of tafsir used here. The Topkapi and British Library copies employ the Tafsir-i Munir of Haddadi (d. circa 1009 AD), a Qur’anic scholar working in Samarqand (Karame and Zadeh 2015). If the present volume uses the same commentary this would provide a further link between the three. If it uses a different commentary, this would introduce an interesting variation. Either way it would shed further interesting light on the exegetical and codicological practices in the eastern Islamic lands at this period.

A fragment of eight leaves from the same Qur’an as the present lot was sold in these rooms, 26 April 1995, lot 5, and is now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (EA2012.73-EA2012.80). It consists of the Qur’anic text of surah al-Baqarah (II), vv.276-282 and surah al-Nisa’ (IV), vv.46-61).

Sotheby’s is grateful to Marcus Fraser for cataloguing this lot.