Collection Hélène Leloup, Le Journal d'une Pionnière, Vol. I

Collection Hélène Leloup, Le Journal d'une Pionnière, Vol. I

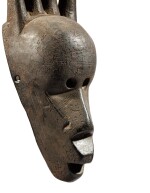

Masque N'Tomo, Bambara, Mali

N'Tomo Mask, Bambara, Mali

Auction Closed

June 21, 04:43 PM GMT

Estimate

30,000 - 50,000 EUR

Lot Details

Description

Masque N'Tomo, Bambara, Mali

haut. 38,5 cm ; 15 1/8 in

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

N'Tomo Mask, Bambara, Mali

Height. 38,5 cm ; 15 1/8 in

Collection Hélène Leloup, Paris, avant 1990

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Hélène Leloup collection, Paris, before 1990

Ndiaye et alii, Arts et peuples du Mali, 1994, p. 58

Leloup, Bambara, 2000, p. 9, n° 1

Colleyn, Bamana. The Art of Existence in Mali, 2001, p. 100, n° 73

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ndiaye et alii, Arts et peuples du Mali, 1994, p. 58

Leloup, Bambara, 2000, p. 9, n° 1

Colleyn, Bamana. The Art of Existence in Mali, 2001, p. 100, n° 73

Amiens, Chapelle de la Visitation, Arts et peuples du Mali, 14 octobre - 26 novembre 1994

Paris, Galerie Leloup, Bambara, juin 2000

New York / Zürich, Museum for African Art / Museum Rietberg, Bamana. The Art of Existence in Mali, 9 septembre - 9 décembre 2001

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Amiens, Chapelle de la Visitation, Arts et peuples du Mali, 14 October - 26 November 1994

Paris, Galerie Leloup, Bambara, June 2000

New York / Zürich, Museum for African Art / Museum Rietberg, Bamana. The Art of Existence in Mali, 9 September - 9 December 2001

Le masque N’tomo de la Collection Hélène Leloup

Par Jean-Paul Colleyn

Ce masque du ntomo, dont j’ai eu l’honneur de publier l’image en 2001, impressionne par sa perfection : c’est une merveille de simplicité et sa forme est très épurée ! Nous l’appelons, ainsi que la société d’initiation éponyme, ntomo, par commodité car c’est l’appellation la plus répandue, mais le même type de masque peut se présenter sous les noms de ndomo, sinton, sindo, cèble, ntori, kefengo, ngonio ou togo, qui sont soit des équivalents du ntomo, soit des classes de cette société. Celle-ci revêt donc des formes variées selon les localités et les époques. Ce masque est l’emblème de la société des garçons non encore circoncis, qui joue le rôle d’école de brousse. La surface du masque présente des traces de matières qui ont été ajoutées après la taille. Il a été d’abord noirci au feu, puis frotté avec du charbon de bois pilé, avant de recevoir des oblations de crème de mil, qui ont notamment laissé des traces entre les cornes. C’est un masque ancien, comme en témoignent l’usure des bords intérieurs du masque et l’érosion des très fines gravures géométriques qui évoquent les scarifications. Il est remarquable en ce qu’il combine trois principes : animal, humain et végétal. L’instrument de musique privilégié du ntomo est le cun, gros tambour hémisphérique, sans parler de deux types de rhombes que manie en certaines occasions le porteur de masque. La fête annuelle du ntomo a lieu à l'époque des récoltes, mais le masque sort également durant la saison sèche pour solliciter auprès des villageois, du mil, d'autres nourritures ou des cadeaux en prévision de la fête

Les masques du ntomo sont des masques faciaux et la face représentée est humaine - ou, du moins anthropomorphe, percée de deux trous pour la vision - mais celui-ci ressemble beaucoup, si ce n’était la rangée de cornes, aux masques sulaw du korè, que portent les initiés de cette société initiatique après la circoncision et l’initiation en brousse, à cette société des hommes adultes. Le masque est maintenu par des liens noués derrière la tête. L'initié destiné à le porter est choisi par les hommes adultes parmi les meilleurs danseurs rituels, mais en principe, son identité est tenue secrète. Son corps est d’ailleurs entièrement recouvert d’un vêtement blanc, ocre ou tacheté, y compris les mains et les pieds. Le « côté sula » de cette pièce invite à penser que ce masque figure l’aspiration des enfants du ntomo à un stade ultérieur du développement de la personne, lors de l’initiation au korè. Les masques sula figurent en effet un état intermédiaire entre la mort des enfants (on dit qu’ils sont « tués au korè ») et l’âge adulte, mais, alors qu’ils appartiennent encore à la nature, ils doivent « rentrer au village ». Accompagnés par un orchestre ambulant, par des porteurs de fouets et de torches, dansant, sautant et criant, ils entrent au village, où les attendent leurs familles. Ce rite, encore pratiqué de nos jours, est toutefois devenu rarissime et très simplifié par rapport aux formes antérieures aux années 1960, dont se souviennent encore quelques patriarches. Le docteur Pascal Imperato a photographié, en 1971, un danseur du ntomo dans un petit village aujourd’hui intégré à la ville de Bamako et où a d’ailleurs été ouvert, trois ans plus tard, l’aéroport de Sénou. Les cornes dont sont pourvus les masques du ntomo renvoient au règne animal, mais aussi végétal et humain. Les cornes s’élèvent à partir de graines qui sont les véritables sources du développement de la personne humaine, selon un parallèle établi avec le règne végétal, notamment dans les contes, devises, prières et chants.

Il ne faut pas se laisser abuser par le terme de société enfantine. A l’époque précoloniale, la circoncision se faisait le plus souvent entre 12 et 20 ans et non dans le bas âge, comme aujourd’hui. Ensuite, l’initiation des « enfants du ntomo » pouvait être rude : elle comportait de nombreuses épreuves dont les échecs étaient sanctionnés par des châtiments corporels. Les initiés eux-mêmes, dès l’âge de 8-10 ans, se lançaient des défis et se flagellaient mutuellement sans émettre le moindre cri, de crainte d’être traités de pleutres pour le restant de leurs jours. Le rôle du ntomo était d’apprendre à « tenir sa bouche », c’est à dire résister à la douleur et respecter les secrets.

La seule origine mentionnée, pour ce masque est celle de la région de Koulikoro, ce qui ne nous renseigne pas beaucoup car elle est immense. Quoi qu’il en soit, les institutions bambara étaient beaucoup moins homogènes et moins linéaires que ne l’ont affirmé les auteurs de l’école française d’ethnographie – Marcel Griaule, Germaine Dieterlen, Viviana Pâques, Dominique Zahan, et Youssouf Tata Cissé. Le ntomo n’était pas une société d’initiation exclusivement bambara : elle était répandue partout où des lignages mandé avaient étendu leur influence et existait, parfois sous d’autres noms, chez les Soninké, les Marka, les Malinké, les Minianka, les Senufo, jusque dans le nord de la Côte d’Ivoire. Notons que le N’tomo est le principal protagoniste du roman de l’écrivain malien Seydou Badian, Noces sacrées, qui raconte l’histoire d’une profanation d’un sanctuaire par un Européen et la sanction mystique qui le frappe.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

The N'tomo Mask of the Leloup Collection

By Jean-Paul Colleyn

This ntomo mask, whose image I had the honor to publish in 2001, impresses by its perfection: it is a marvel of simplicity and its form is very pure! We call it, as well as the eponymous initiation society, ntomo, for convenience because it is the most widespread name, but the same type of mask can be presented under the names of ndomo, sinton, sindo, cèble, ntori, kefengo, ngonio or togo, which are either equivalents of ntomo, or classes of this society. This society therefore takes on various forms depending on the locality and the period. This mask is the emblem of the society of uncircumcised boys, which plays the role of a bush school. The surface of the mask shows traces of materials that were added after cutting. It was first blackened with fire, then rubbed with crushed charcoal, before receiving oblations of cream of millet, which notably left traces between the horns. It is an ancient mask, as evidenced by the wear of the inner edges of the mask and the erosion of the very fine geometric engravings that evoke scarification. It is remarkable in that it combines three principles: animal, human and vegetable. The privileged musical instrument of the ntomo is the cun, a large hemispherical drum, not to mention two types of rhombes that the mask wearer wields on certain occasions. The annual ntomo festival takes place at harvest time, but the mask also goes out during the dry season to solicit millet, other foods or gifts from the villagers in anticipation of the festival.

The masks of the ntomo are facial masks and the face represented is human - or at least anthropomorphic, with two holes for vision - but this one looks very much like the sulaw masks of the kore, worn by the initiates of this initiation society after circumcision and initiation in the bush, to this society of adult men, if it were not for the row of horns. The mask is maintained by ties tied behind the head. The initiate destined to wear it is chosen by the adult men from among the best ritual dancers, but in principle his identity is kept secret. His body is entirely covered with a white, ochre or spotted garment, including his hands and feet. The "sula side" of this piece suggests that this mask represents the aspiration of the children of the ntomo at a later stage of personal development, during the initiation into the kore. The Sula masks represent an intermediate state between the death of the children (they are said to be "killed in the kore") and adulthood, but while they still belong to nature, they must "return to the village. Accompanied by a travelling band, by whip and torch bearers, dancing, jumping and shouting, they enter the village, where their families await them. This rite, still practiced today, has however become rare and very simplified compared to the forms before the 1960s, which some patriarchs still remember. In 1971, Dr. Pascal Imperato photographed a ntomo dancer in a small village that is now part of the city of Bamako and where, three years later, the airport of Sénou was opened. The horns on the ntomo masks refer to the animal kingdom, but also to the plant and human kingdoms. The horns grow from seeds which are the true sources of the development of the human person, according to a parallel established with the plant kingdom, notably in the tales, mottos, prayers and songs.

One should not be misled by the term "child society". In pre-colonial times, circumcision was most often carried out between the ages of 12 and 20, and not at an early age, as today. Then, the initiation of the "children of the ntomo" could be harsh: it included numerous tests, the failures of which were sanctioned by corporal punishment. The initiates themselves, from the age of 8-10, would challenge each other and flog each other without uttering the slightest cry, for fear of being called cowards for the rest of their lives. The role of the ntomo was to learn how to "hold one's mouth", i.e. to resist pain and respect secrets.

The only origin mentioned for this mask is that of the Koulikoro region, which does not tell us much because it is immense. In any case, Bambara institutions were much less homogeneous and less linear than the authors of the French school of ethnography - Marcel Griaule, Germaine Dieterlen, Viviana Pâques, Dominique Zahan, and Youssouf Tata Cissé - have claimed. The N'tomo was not an exclusively Bambara initiation society: it was widespread wherever Mande lineages had extended their influence and existed, sometimes under other names, among the Soninké, the Marka, the Malinké, the Minianka, the Senufo, even in the north of the Ivory Coast. The N'tomo is the main protagonist of the Malian writer Seydou Badian's novel, Noces sacrées, which tells the story of the desecration of a sanctuary by a European and the mystical punishment that strikes him.