Books, Manuscripts and Music from Medieval to Modern

Books, Manuscripts and Music from Medieval to Modern

Charles Dickens | Autograph manuscript chapter outline of David Copperfield

Lot Closed

July 18, 02:08 PM GMT

Estimate

40,000 - 60,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

Charles Dickens

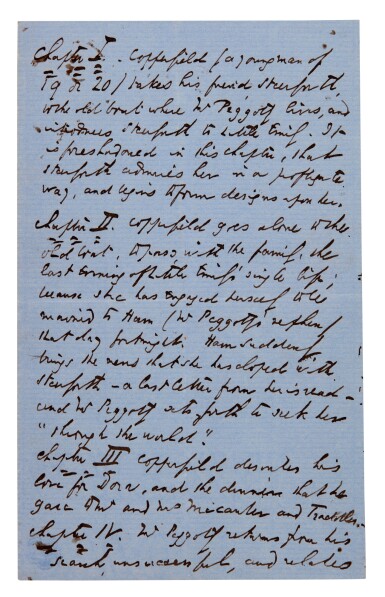

Autograph manuscript chapter outline of David Copperfield

2 pages, text on rectos only, small 8vo (182 x 113mm), on a single bifolium of light blue laid paper (watermarked "Towgood's Extra Super"), blind-stamped in lower margin, [1855-61], previously folded,slight wear at folds

A UNIQUE INSIGHT INTO HOW DICKENS ENVISIONED HIS "FAVOURITE SON" ADAPTED FOR PUBLIC RECITAL. Dickens had to pare down his narrative significantly in order to adapt it into a reading of under 2 hours, and he wrote in January 1855 of the "huge difficulty" he faced when "separat[ing] the parts as to tell the story of David's married life with Dora, and the story of Mr. Peggotty's search for his Niece, within the time" (letter to Arthur Ryland, 29 January 1855, in Letters, Vol.7, p.515).

Most of Dickens's reading texts condensed a short story in its entirety, honed in on a single key episode, or provided a focused character study, but his adaptation of David Copperfield was more complex: "with Copperfield he was trying to do all three [...] encompassing a developing narrative (the story of Emily and Steerforth) [...] some of the famous characters (the Micawbers, Mr Peggotty) [...] and [...] strong single episodes (most notably the storm at Yarmouth) [...] the organization of the Reading is masterly. Dickens had shaped the narrative into a series of striking scenes, finely adapted for performance—"a series of tableaux", as one reviewer put it" (Andrews, Charles Dickens and his Performing Selves, pp.87-90)

Dickens organised his reading into five and later into six chapters, and the current text is a summary of the latter version:

"Chapter I. Copperfield (a young man of 19 or 20) takes his friend Steerforth to the old boat where Mr Peggotty lives, and introduces Steerforth to Little Emily. It is foreshadowed in this chapter, that Steerforth admires her in a profligate way, and begins to form designs upon her.

Chapter II. Copperfield goes alone to the old boat, to pass with the family, the last evening of Little Emily's single life; because she has engaged herself to be married to Ham (Mr Peggotty's nephew) that day fortnight. Ham suddenly brings the news that she has eloped with Steerforth - a last letter from her is read - and Mr Peggotty sets forth to seek her "through the world".

Chapter III. Copperfield describes his love for Dora, and the dinners that he gave to Mr and Mrs Micawber and Traddles.

Chapter IV. Mr Peggotty returns from his search, unsuccessful, and relates where he has been in France and Italy.

Chapter V. Copperfield describes how he made proposals to Dora - how be married Dora - and what their little ménage was.

Chapter VI. Describes the storm at Yarmouth, in the words of the book, and the Death of Steerforth."

Dickens subtly alters the novel's sequence of events, so that "David's falling in love with Dora and the meal with the Micawbers are placed after the news of Emily's elopement", thereby creating an "appealing symmetry" in the narrative structure between the sacred love of David and Dora, on the one hand, and the profane love of Steerforth and Emily, on the other hand (see Andrews). It is also notable that Dickens ends this revised narrative structure on a tragic apotheosis, with the storm at Yarmouth and Steerforth's untimely death (to be recounted faithful "to the words of the book"), as opposed to with David's happy marriage, as had been the case at the end of the novel.

The adaptation came to be Dickens's favourite public reading. It was physically exhausting but Dickens was thrilled by its powerful effect. The potency of the reading's climax - the fatal storm at Yarmouth - was vividly recalled by those fortunate enough to hear Dickens read:

"Listening to that Reading, the very portents of the coming tempest came before us!—the flying clouds in wild and murky confusion, the moon apparently plunging headlong among them, “as if, in a dread disturbance of the laws of nature, she had lost her way and were frightened,” the wind rising “with an extraordinary great sound,” the sweeping gusts of rain coming before it “like showers of steel,” and at last, down upon the shore and by the surf among the turmoil of the blinding wind, the flying stones and sand, “the tremendous sea itself,” that came rolling in with an awful noise absolutely confounding to the beholder! In all fiction there is no grander description than that of one of the sublimest spectacles in nature. The merest fragments of it conjured up the entire scene—aided as those fragments were by the look, the tones, the whole manner of the Reader. (Charles Kent, Charles Dickens as a Reader (1872), p.35)

LITERATURE

E.W.F. Tomlin, 'Newly Discovered Dickens Letters', Times Literary Supplement, 22 February 1974, 183-186; Charles Dickens: The Public Readings, ed. Philip Collins (1975), p.215; Malcolm Andrews, Charles Dickens and his Performing Selves (2007), pp. 87-90

PROVENANCE

Ernest Legouvé (1807-1903), thence by descent to Jean Paladilhe