Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library. Magnificent Books and Bindings

Bibliotheca Brookeriana: A Renaissance Library. Magnificent Books and Bindings

Pacioli, Divina proportione; Euclid, Opera, Venice, Paganini, 1509, the only editions of Luca Pacioli's most significant works

Auction Closed

October 11, 11:51 PM GMT

Estimate

275,000 - 350,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Pacioli, Luca. Diuina proportione. Opera a tutti glingegni perspicaci e curiosi necessaria oue ciascun studioso di philosophia: prospectiua pictura sculptura, architectura, musica, e altre mathematice, suauissima, sottile, e admirabile doctrina consequira e delectarassi con varie questione de secretissima scientia. M. Antonio Capella eruditiss. recensente. Venice: Paganino I Paganini & Alessandro Paganini, June 1509. Bound with:

Euclides, Euclidis Megarensis philosophi acutissimi mathematicorumque omnium sine controuersi principis Opera a Campano interprete fidissimo tralata … Lucas Paciolus theologus insignis, altissima mathematicarum disciplinarum scientia rarissimus iudicio castigatissimo detersit, emendauit. Figuras centum & undetriginta que in alijs codicibus inuerse & deformate erant, ad rectam symmetriam concinnauit, & multas necessarias addidit. Eundem quoque plurimis locis intellectu difficilem commentariolis sane luculentis &eruditiss. aperuit, enarrauit, illustrauit. Adhec vt elimatior exiret Scipio Vegius Mediol. vir vtraque lingua, arte medica, sublimioribusque studijs clarissimus diligentiam & censuram suam prestitit. Venice: Paganino I Paganini & Alessandro Paganini, 11 June 1509 (colophon: 22 May 1509)

Only editions of two works by the humanist educator Luca Pacioli (1446/7–1517), his famous book on mathematical proportions and their applications to the visual arts and architecture, with illustrations cut from designs by Leonardo da Vinci; and his revision of Euclid’s Elements, a tidying-up of the Campanine text printed in 1482. The two books were issued almost simultaneously at the Venetian press of Paganino and Alessandro Paganini, where in 1494 Paganino Paganini had printed Pacioli’s encyclopedic Somma di arithmetica. Both works contain dedicatory addresses (to the humanist Daniele Renier and Senator Andrea Mocenigo, respectively) and verses contributed by the Cremonese mathematician and rhetorician Daniele Caetani (1461–1528), and both are protected by the same fifteen-year privilege, granted to the author, 19 December 1508.

The Divina proportione is a compendium of contemporary mathematical ideas organized in three parts. The first, a discussion of “divine proportion” with a focus on the proportion we now call the “golden ratio,” in seventy-one chapters, was completed in 1498 while Pacioli was employed in Milan as a public lecturer in mathematics in the Scuole Palatine; the printed edition retains the dedication to Ludovico Sforza of the two surviving manuscripts (Geneva, Bibliothèque de l’Université, Ms 210; Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Ms 170). The second part is a “Trattato dell’architettura,” in twenty brief chapters, treating the proportions of Vitruvian architecture and the art of perspective; it is dedicated by Pacioli to his students in Sansepolcro. The third part is an Italian translation of Piero della Francesca’s unpublished work on the five regular solids, the Libellus de quinque corporibus regularibus; it is dedicated to the Florentine gonfaloniere Piero Soderini, who receives the dedication of the entire book (1 May 1509), and presumably supported its publication.

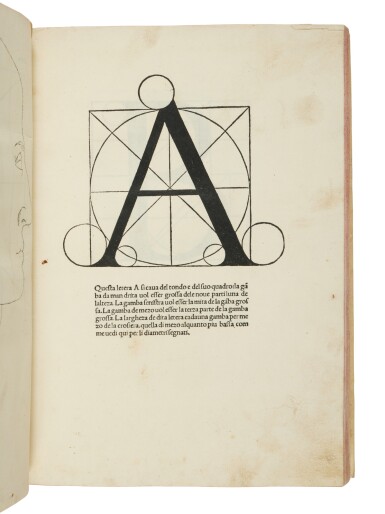

In the text, Pacioli identifies his close friend Leonardo da Vinci as the artist who drew the regular and semi-regular polyhedra (although sixty appear in the two presentation manuscripts, one is omitted in the printed book). The name of Leonardo da Vinci is mentioned repeatedly in various passages of this book, and his Last Supper, painted for Ludovico at Milan, is mentioned particularly in Chapter XIII. Pacioli does not identify who drafted the equally celebrated series of twenty-three Roman capital letters, each measuring about 95 mm and printed on separate pages: several critics conjecture they also were drawn by Leonardo, others propose the painter Andrea Mantegna, who knew Pacioli and who had worked with Felice Feliciano on his geometrically constructed alphabet; and some promote Leon Battista Alberti. A woodcut profile of a netted head (f. 25v) is believed to be copied from a manuscript of Piero della Francesca’s. At the end is a woodcut genealogical tree of proportion and proportionality, copied from the block in Pacioli's 1494 Somma di arithmetica. All the illustrations presumably were cut by an artisan working for the Paganini.

The companion work bound here is the only edition of Pacioli’s “restoration” of Euclid’s Elements, a defense of Campanus of Novara’s thirteenth-century redaction from Latin manuscripts of Arabic origin (first printed by Erhard Ratdolt, Venice 1482; reprinted Vicenza 1491) against the calumnies of Bartolomeo Zamberti, who had published the Elements at Venice in 1505, from the original Greek. Zamberti had described Campanus as that "most barbarous translator” (interpres barbarissimus), complaining that he had filled a volume purporting to be Euclid’s with “extraordinary scarecrows, nightmares and phantasies” (miris larvis, somniis et phantasmatibus). On the title-page of his edition, Pacioli presents Campanus as “interpres fidissimus,” and himself as a “corrector” (castigator), weeding Campanus’s text of errors introduced by copyists, particularly incorrectly drawn diagrams (Pacioli states on the title that 130 of these are corrected and clarified). A comparison by Menso Folkerts of Pacioli’s edition with the 1482 edition of the Campanus text revealed 136 instances where Pacioli added commentary or a gloss, of which forty-two were more than ten lines long, mainly explanations of terms or of steps within a proof, such as Pacioli would have given in his mathematical lectures (“Luca Pacioli and Euclid,” in Luca Pacioli e la matematica del rinascimento [Città di Castello, 1998], pp. 219–231).

Notwithstanding the modesty of this intervention, Pacioli’s version of the Elements is seen as the product of lifelong study: commencing with instruction he had received as a boy in the humanist grammar school in Sansepolcro (allegedly from Piero della Francesca), continued as a student at the university of Perugia, and consummated as a teacher in Florence, and in Naples (where he compared Campanus’ text with a Greek manuscript acquired by the Duke of Urbino).

In the arithmetical part of his Summa de arithmetica (1494), Pacioli gave excerpts from the fifth book, and in the geometrical part excerpts from books 1–3, 6, and 11. In the famous portrait by Jacopo de’ Barbari, dated 1495, Pacioli is shown as a master of Euclidean geometry, his hand resting on a printed edition of the Elements—not a copy of the 1482 or 1491 editions, but a nonexistent edition, presumably one Pacioli intended to make himself (see Baldasso “Portrait of Luca Pacioli and Disciple,” in The Art Bulletin 92 (2010), pp. 83–102). Between 1494 and 1497 Pacioli was preparing an Italian translation of the Elements and in the dedicatory letter of the Divina proportione (1509) he advertises it as forthcoming (the work unfortunately is lost). In 1507–1508, he was in Venice, lecturing on the Elements both at the Scuola di Rialto and in public: a discourse Pacioli delivered 11 August 1508 before an audience of five hundred in San Bartolomeo, Venice, is printed in 1509 as a preface to the fifth book. Ninety-four attendees of the lecture are listed by Pacioli, among them Aldo Manuzio, Pietro Bembo, and Fra Giocondo, editor of the 1511 Vitruvius. The unusual venue for this public lecture (San Bartolomeo was the German church in Venice) led Thomas L. Heath to conjecture that Erhard Ratdolt—publisher of the 1482 edition, now returned to Augsburg—organized it and also financed Pacioli’s edition (The Thirteen Books of Euclid’s Elements [Cambridge, 1926], I, p. 99).

2 works in one volume, Royal 4to (279 x 198 mm). (I) Roman type, 57 lines plus headline. collation: A6 b–d8 E10 a–b8 c10 [d–o8]: 154 leaves (E10, [o8] blank), the last 88 leaves unsigned, each (save the terminal blank) with a full-page woodcut illustration printed on the recto, including 23 depicting letters, the final plate depicting a genealogical tree printed in red and black. Title printed in red and black with woodcut criblé initial D, numerous diagrams in margin of text, numerous white-on-black woodcut initials with criblé, knotwork, floral or ornithological ornament. II: Roman type, 57 lines plus headline. collation: a10 b–s8: 146 leaves (s8 blank). Title printed in red and black with white-on-red criblé initial E, geometrical diagrams in the fore-edge margins, numerous woodcut criblé and other initials from several series. (Some scattered light marginal staining and soiling, a very few marginal tears; first work with sketches, one artless, after the woodcut on [d1] on c10v and [d1]v; second work with minor loss to lower margins of kiiii–vi.)

binding: Eighteenth-century Italian vellum over pasteboards (285 x 200 mm), cords pierced through spine at head and tail, flat spine, red-sprinkled edges. (Short tear at foot of front joint.)

provenance: Early marginalia of unidentified owner(s): pointing hands in ink in margins of Pacioli, contemporary marginalia (cropped) in Euclid (pp. 13–14, 53–54) — “Feltre” (in inscription on first title-page (lined through; unidentified). acquisition: Purchased from Libreria antiquaria Mediolanum, Milan, 2012.

references: (I) Edit16 28200; USTC 846001; Nuovo, Alessandro Paganino, no. 2; Mortimer, Italian, no. 346; (II) Edit16 18350; USTC 828472; Nuovo, no. 1.