Auktionen

Buy Now

Collectibles & Mehr

Bücher & Manuskripte

Aboriginal Art

Aboriginal Art

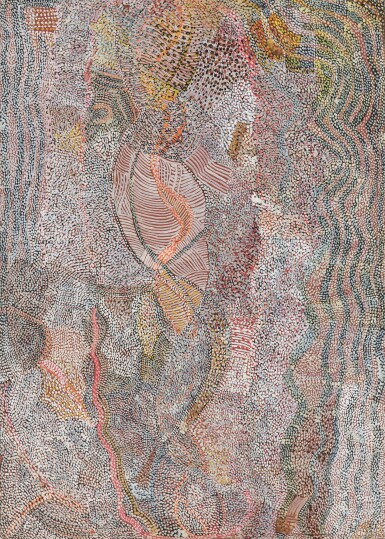

Water and Bush Tucker Story

Auction Closed

May 23, 09:01 PM GMT

Estimate

400,000 - 600,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula

circa 1932-2001

Water and Bush Tucker Story, 1972

Bears the Stuart Art Centre label (distressed) with catalogue number 1272149 on the reverse of frame

Synthetic polymer paint on composition board

25 ¾ in x 18 ⅛ (65.5 cm x 46 cm)

Painted at Papunya, Northern Territory, 1972

Stuart Art Centre, Alice Springs (catalogue number 1272149)

Private Collection, acquired from the above

Sotheby’s, Sydney, Aboriginal Art, October 20, 2008, lot 99

Private Collection, acquired from the above

Judith Ryan and Philip Batty, Tjukurrtjanu: Origins of Western Desert Art, Melbourne, 2011, p. 271

Judith Ryan and Philip Batty, Tjukurrtjanu: Aux sources de la peinture àborigene, Paris, 2012, p. 271

John Kean, Dot, Circle and Frame: the making of Papunya Tula Art, Perth, 2023, p. 258 (illus.)

The lan Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne, Tjukurrtjanu: Origins of Western Desert Art, September 30, 2011 - February 12, 2012 (label on the reverse of frame); additional venues:

Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, October 9, 2012 - January 20, 2013

Johnny Warangula Tjupurrula’s artistic agency arose from his status as a rainmaker. Fortunately for the history of Australian art, the commencement of full-scale painting at Papunya coincided with a period of consistent heavy rain, a powerful muse that gave added momentum to Warangula’s inextinguishable creative urge. Water & Bush Tucker Dreaming (1972) was painted during a period of intense creative output in the spring of 1972. Geoffrey Bardon regards Warangula’s Water Dreaming series (1971-1973), of which Water & Bush Tucker Dreaming is an exemplar, as ‘the finest achievement of Western Desert Painting Movement.’1 The variety and complexity of Warangula’s paintings in this series, can in part, be attributed to the inherently lyrical qualities of Water Dreaming iconography, however instead of simply recapitulating customary icons, Warangula shattered the signs for lightning and running water to present a cadenza of dots, sinuous segments and staccato bars that jostle and surge within a vibrant pictorial ecology.

Warangula’s marks were intended to transport us sensually and metaphysically into the heart of the storm. Indeed, the painterly touch of Warangula’s Water Dreaming series epitomises Munn’s assertion that ‘the bodily identification of a man with the ancestors takes place through sensory contact with ancestral guruwari’(ancestral sign or essence).2

Where rarrk (the cross-hatching in Yolngu art of Northeast Arnhem Land) and the ceaseless concentricity of Western Desert minimalism rely for their effect on precision, Warangula’s optical shifts arise from irregularity. Noting the affinity between some naturally occurring phenomena and intentional irregularities in art, the anthropologist and linguist Peter Sutton draws our attention to the iridescent nacre of pearl:

"With iridescence, any visual assumption of continuity fails. Looking at a small part of the image is of little help in guessing what the next part of the image will look like. Simple regularities are absent, so extrapolation from one part to whole is difficult, to say the least. The eye wanders from surprise to surprise."3

Just as light shifts unpredictably deep within the polished surface of a pearl shell, Warangula’s inflected field disrupts what art historian Ernst Gombrich termed the ‘continuity assumption’.4 Warangula found that if the expectation of iconographic legibility was unsettled with unpredictable dots and dashes, the eye would be stimulated to search deeper for the underlying structure.

The analogy between iridescence and the swaths of dotted patches that overlay Warangula’s painting is intentional, almost literal, for pearl shells are fundamental to rituals associated with ‘rain making’. Significantly, the pendant-like form at the heart of Water & Bush Tucker Dreaming resembles a pearl shell, and the sinuous pink lines (marked with white dots) that overlay that shape, suggest the hair string from which pearl shells are frequently suspended in desert ritual. The ultimate origin of pearl shells was a mystery in the desert, for this potent material was exchanged along extensive trade routes from its source on the Kimberley Coast. Unsurprisingly, lustrous pearl shells were imbued with increasing power (and danger) the further they were carried from the salty depths from which they were collected.5 The visual affinity between the iridescence of a pearl shell and the emergence of tiny rain clouds on the horizon, the prismatic light dispersed through a single raindrop, or through many, to form the overarching spectrum array of a rainbow, excite an assumption of equivalence across desert cultures. Rainmakers activate the affinity between these phenomena to conjure the elements of a storm:6

"Power is transformation, in that we only know it is real by its effects, when it becomes something else, such as movement or brightness … Rainbows and rain were to pearl shells as macro is to micro in just this sense, in the traditions of Central Australia. These unruly meteorological elements became literally manipulable, handleable by people."7

The association of pearl-like sparkling materials with Water Dreaming icons is manifest in Water & Bush Tucker Dreaming (1971–72; Fig. 154), a work in which Warangula’s pictorial inventions are distilled to create a scintillating veil of everchanging light and percussive gesture.

Warangula’s paintings have been compared with those of Camille Pissarro and Paul Signac, whose pure dabs of colour animated the surface of the canvas.8 Unaware of the optical theory that informed pointillism, Warangula plumbed his repertoire as a songman to create a dynamic innovative vision. His metaphysical prowess afforded him the agency to atomise elements of classical iconography. As an embodiment of Winpa, the Lightening ancestor, Warangula summoned the living light associated with meteorological phenomena (lightening, clouds, rainbows and the light refracted through drops of rain). His paintings can thus be understood to ‘make’ light, via lightning, rather than merely replicate its effect on the material world, as was the case with the French Impressionists.

While his closest peers, including Kaapa Tjampitjinpa, Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri and Long Jack Philliipus Tjakamarra refined their compositions according to the spatial relations of the ceremonial ground, Warangula envisaged Country through the intuitive ‘performance’ of painting. He applied dots in combination with ovals, arcs and dashes to initiate dynamic shifts in direction, transparency and hue. He rendered the surface of his paintings alive, the dot and the fluency of his wrist becoming the most vital elements of his painterly register. The influence of Warangula’s technique can be sensed in many of the greatest works produced at Papunya in the 1970s.9

John Kean

April 2023

John Kean was Art Advisor at Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd, (1977-9) inaugural Exhibition Coordinator at Tandanya: the National Aboriginal Cultural Institute (1989-92) Exhibition Coordinator at Fremantle Arts Centre (1993-6) Producer with Museum Victoria (1996-2010). He has recently completed a PhD in Art History at the University of Melbourne. John has published extensively on Indigenous art and the representation of nature in Australian museums.

1 Geoffrey Bardon and James Bardon, Papunya: a place made after the story : the beginnings of the Western Desert painting movement, Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2004, p. 32.

2 Nancy D. Munn, Walbiri Iconography: Graphic Representation and Cultural Symbolism in a Central Australian Society, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1973, p. 30.

3 Sutton, in Peter Sutton and Michael Snow, Iridescence: the play of colours, Port Melbourne: Thames & Hudson Australia, 2015, p. 161.

4 Gombrich 1979, quoted in Sutton & Snow 2015, p. 161.

5 Kim Akerman and John Stanton, Riji and Jakuli: Kimberley pearl shell in Aboriginal Australia, Series No. 4, Darwin: Northern Territory Museum of Arts and Sciences, 1994.

6 Charles Mountford, Nomads of the Australian Desert, Adelaide: Rigby, 1976, pp. 273–75.

7 Sutton, in Sutton & Snow 2015, p. 152.

8Judith Ryan, ‘Aesthetic splendour, cultural power and wisdom: early Papunya painting’, in Tjukurrtjanu: Origins of Western Desert Art, Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2011, p. 25.

9 This essay is in large part comprised of excerpts from: John Kean, Dot, Circle and Frame: the making of Papunya Tula, Perth, Western Australia: Upswell Publishing, 2023, pp, 256-251.

Cf. For similar and related works by the artist see A Bush Tucker Story, 1972, in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Water Dreaming at Kalipinypa, 1972, and Rain Dreaming at Kalipinypa, 1973, in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia. These three works are illustrated in Perkins. H. and H. Fink (eds.), Papunya Tula: Genesis and Genius, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2000, p. 60, p. 63, and p. 65 respectively.

Image Credits:

Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, Papunya, 1972. Photographer Allan Scott