SUBLIME BEAUTY: Korean Ceramics from a Private Collection

SUBLIME BEAUTY: Korean Ceramics from a Private Collection

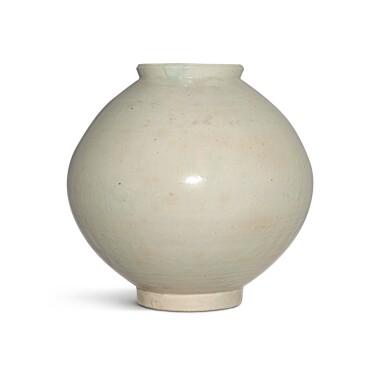

A white-glazed moon jar, Joseon dynasty, late 17th / early 18th century

Lot Closed

September 22, 02:03 PM GMT

Estimate

180,000 - 250,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

A white-glazed moon jar

Joseon dynasty, late 17th / early 18th century

Japanese wood box (3)

Height 14⅛ in., 36 cm

Christie's New York, 26th March 1991, lot 285

Moon jars (dalhangari) are named for their spherical form and white color which evoke a full moon. The unique hue of each jar depends on the natural properties of the clay used in its production, and the effect of the thin glaze on its surface which varies from transparent to slightly milky in tone. From their inception, these vessels have been admired for their minimalist aesthetic, in which the plentiful proportions coexist harmoniously with the restrained surface treatment, qualities that equate to contemporaneous neo-Confucian values extolling the moral fullness that accompanies a life dedicated to pursuing purity, modesty, and essential truths.

Along with other white porcelaneous wares, moon jars were first produced in the official kilns near the capital city of Hanyang (present-day Seoul) during the Joseon dynasty (1392-1910). These kilns were established in the late 1460s to supply vessels to the royal court for use in daily life and state rituals. The production of these vessels was highly regulated, with government-appointed supervisors overseeing the selection of raw materials and the fabrication of the ceramics. One of the earliest, and most important, official wares produced in white kaolin clay at these kilns were the blue and white ‘dragon’ jars, which were inspired by Chinese blue and white ‘dragon’ vessels given by the Xuande Emperor (r. 1425-1435) to King Sejong (r. 1418-1450). Characterized by a baluster shape surmounted by a short neck, these ‘dragon’ jars were important implements in royal Joseon ceremonies in the 15th and 16th century. However, the cobalt used in the design had to be imported through China and the geopolitical circumstances of the late 16th through 17th century—notably two Japanese invasions of Korea (1592 and 1598), two Manchu invasions of Korea (1627 and 1636), and a long and tumultuous dynastic transition in China—made it nearly impossible for Korean potters to obtain cobalt during that period. By the end of the 17th century, the use of cobalt and other luxury products was formally banned through sumptuary laws designed to preserve the state’s financial resources in the midst of a socioeconomic crisis. As a result, Joseon ceramicists of the 17th century relied on indigenous materials and inspiration, and began crafting monochrome white wares, including dishes, bowls, vases, and moon jars.

Excavations of the pottery shards from the official kiln sites reveal that moon jars were first made in the early 1600s, and their popularity grew throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, when private kilns began imitating the newly iconic form. Moon jars were produced by forming two roughly hemispherical bowls on a wheel, joining them together at the rims to form the upper and lower halves of the jar, dipping the resulting jar in a transparent or white-tinged translucent glaze, and firing it at a high temperature. The craftsmen took care to make the two halves compatible, but to avoid making them identical. Subtle irregularities between the upper and lower body, the contours of the sides, and the tonality and texture of the surface, were retained in the finished product to reveal the process and materials unique to each jar. In other words, the potter had to restrain himself from overly refining the jar, lest his extra effort strip out the qualities of the clay and human touch that give the vessel its vitality.

The sensibility of 17th and 18th century moon jars are highly emblematic of the political, intellectual, and cultural context in which they were produced. During that period, Korea turned inward from its neighbors due to the aforementioned tensions, giving rise to distinctly Korean art forms which were independent of creative practices in neighboring China and Japan. At the same time, neo-Confucianism was the official state doctrine and underpinned all aspects of society. The ideology advocated achieving societal and cosmological harmony through the correct performance of rites, the fulfilment of social hierarchies and responsibilities, dedication to moral cultivation, and the observation of nature, particularly with respect to understanding the forces that influence the universe and the mind - li 理 (fundamental principal) and qi 氣 (essential energy). The austerity, purposefulness, and discipline required to achieve these ideals are reflected in the chaste aesthetic of the moon jar. Moreover, the artisans’ eschewal of expensive, non-native, flamboyant cobalt ornamentation, and indeed any decoration whatsoever, demonstrates their prioritization of frugality over excess, pragmatism over whimsy, purity over corruption, and the indigenous over the foreign; values promoted by the Silhak (‘practical learning’) school of Korean neo-Confucian thought which became influential from the late 17th century onwards. That the moon jar could be used as a humble storage container further enhanced its appeal to craftsmen and consumers who adhered to Silhak principals. At a metaphysical level, the transformation of a piece of earth, worked by human hands, into a form echoing a celestial body, which preserves the natural idiosyncrasies of its fundamental material and creator, gives moon jars their universal visual appeal, and allows them to embody the neo-Confucian pursuit of harmoniously integrating the three realms of the universe: earth, man, and the cosmos. For these reasons, moon jars of the 17th and 18th century are considered a quintessential expression of mid- to late Joseon culture.

17th and 18th century Joseon moon jars are preserved in numerous museum collections worldwide. Compare two 17th century examples—one housed in the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago (accession no. 2001.413), the other in the National Museum of Korea, Seoul (accession no. Jeopsu 702). A jar attributed to 1650-1750 was formerly in the Avery Brundage Collection and is now in the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco (accession no. B60P110+). A 17th or 18th century example is in the National Palace Museum of Korea, Seoul (National Treasure no. 310). Moon jars attributed to the early 18th century include one formerly in the collection of Charles B. Hoyt, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (accession no. 50.1040), and one exhibited in Special Exhibition of Ewha Womens University Museum’s 80th Anniversary: White Porcelain in the Joseon Dynasty, Ewha Womens University Museum, Seoul, 2015, cat. no. 019. For examples attributed to the 18th century, compare a jar in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit (accession no. 1982.4); one in the Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland (accession no. 1983.28); one formerly owned by the influential 20th century British potters Bernard Leach and Dame Lucie Rie and now in the collection of the British Museum, London (accession no. 1999,0302.1); and a further example in the Leeum Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul (National Treasure No. 309).