Important Chinese Art

Important Chinese Art

Property from an American Private Collection

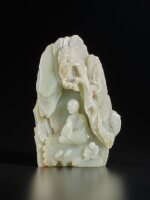

An inscribed pale celadon jade 'Luohan' boulder, Mark and period of Qianlong, dated dingchou year, corresponding to 1757 | 清乾隆丁丑年 (1757年) 青白玉雕拔嘎沽拉尊者山子 《大清乾隆年造》款

Auction Closed

September 21, 06:54 PM GMT

Estimate

60,000 - 80,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

An inscribed pale celadon jade 'Luohan' boulder

Mark and period of Qianlong, dated dingchou year, corresponding to 1757

清乾隆丁丑年 (1757年) 青白玉雕拔嘎沽拉尊者山子 《大清乾隆年造》款

the base incised with a six-character Qianlong nianzao mark, followed by a single character jiu (nine)

字:九

釋文:

第九位拔嘎沽拉尊者 丁丑

軒鼻呴口 數珠在手 萬法皈一 一法不受 婆羅樹下 兀然忘形 演無聲偈 有童子聽

Height 8¼ in., 21 cm

Sotheby's New York, 19th-20th October 1988, lot 259.

紐約蘇富比1988年10月19至20日,編號259

The present sculpture, carved from a tall jade boulder, capitalizes on the material’s inherent qualities to create a towering stone grotto framing the Luohan Nakula who is seated in solitude with a sutra in hand and a censer burning nearby. The cavernous setting has been expertly crafted to give the impression of raw naturalism, while simultaneously providing the artisan with the requisite surfaces to render the luohan almost completely in the round and provide a frontal flat plane to accommodate the descriptive inscription. The inscription identifies the figure as Nakula, here called the ninth luohan, and includes the cyclical characters dingchou, corresponding to the year 1757. Usually referenced as the fifth of the standard set of sixteen, the luohan is known as Nalkula in Sanskrit and Jialijia Zhunzhe in Chinese. The inscribed text complements the carving as it describes Nakula as meditating under a sal tree, holding a rosary, and attended by a young acolyte. Like all luohan, he is a protector of Buddhism and its practitioners, particularly during periods of danger or instability.

The pictorial boulder follows the Qianlong Emperor’s standards for adaptations of classical paintings carved in stone. This image of Nakula can be traced to the portrait series of the sixteen luohan painted by the Tang dynasty painter-poet-monk, Guanxiu (832-912), in 891. In it, the artist depicted the enlightened disciples with distorted bodies, hunched backs, bushy eyebrows, and pronounced foreheads, as they had allegedly appeared to him in a dream. He then labeled each portrait with the Sinicized name of the luohan, in according with the pilgrim Xuanzang’s (596-664) translation of the Fahua jin (Annotated Record of Buddhism). These bizarre portraits captured the imaginations of devotees, and the series was preserved in the Shengyin Temple near Qiantang (now Hangzhou) until 1861.

In 1757, the same year that the present carving was made, the Qianlong Emperor visited the Shengyin Temple during his Southern inspection tour to study the portraits as an act of religious devotion. There is some debate as to whether the emperor viewed the original paintings or later copies, but in any case, he recorded that he had seen the masterpieces by Guanxiu and was inspired to personally study their contents and have their images proliferated. As a serious practitioner of Buddhism, the emperor noticed that the names on each of the portraits did not conform to the Sanskrit, so he annotated the paintings with the corrected names and reordered them according to his own teacher’s interpretation of their sequence in the Tongwen yuntong (Unified Rhymes). The Emperor then penned two colophons on each painting, respectively eulogizing and reidentifying the luohan depicted. On the painting of the sixteenth luohan, Abheda, he also added a lengthy colophon describing his process of studying and reattributing each image.

Subsequently, the Qianlong Emperor commanded the palace painting master, Ding Guanpeng (act. 1708-ca. 1771) to copy the paintings and the new inscriptions that he had applied to them. Ding’s copies are now in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, and published Gugong shuhua tulu / Illustrated Catalog of Chinese Painting in the National Palace Museum, vol. 13, Taipei, 1994, pp 183-214. Over the decades, the emperor had the images reproduced in additional media, including textiles and jades.

In 1764, the abbot at Shengyin Temple, Master Mingshui, instructed local stone engravers to copy Guanxiu’s paintings and the Emperor’s colophons and seals. The sixteen engraved stone panels were installed on the sixteen sides of the Miaoxiang Pagoda in Hangzhou. Rubbings of the engravings were made by adherents as acts of piety, allowing the images and the Emperor’s comments to proliferate further. The rubbings taken from it, as well as stone copies of the stele, are also preserved in museums, libraries, and private collections to this day. The pagoda and its carvings have since been moved to the Hangzhou Stele Forest.

From the outset, the rubbings were widely admired. Knowing the Emperor’s fondness for them, in 1778, the military governor of Shandong province, Guotai (d. ca. 1782), presented the Qianlong Emperor with a magnificent zitan folding screen set with black lacquer panels inlaid with white jade in imitation of the rubbings. The Emperor was so impressed by the splendid gift that he had the Yunguanglou (Building of Luminous Clouds) of the Imperial Palace completely redesigned to accommodate and complement it. The illustrious screen remains part of the Qing Court Collection at the Palace Museum, Beijing, and was exhibited in the traveling exhibition The Emperor’s Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, 2010, cat. no. 49.

A similar celadon jade boulder featuring the third luohan, Vanavasa, which generally follows Guanxiu’s design and inscribed with the two imperial colophons, and a six-character reign mark, sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 27th April 2003, lot 22. A related white jade boulder depicting the sixteenth luohan, Abheda, inscribed with an imperial eulogy and dated to 1758, from the Crystalite Collection, sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 30th May 2016, lot 3021. See also a closely related but smaller jade boulder of the sixteenth luohan, Abheda, formerly part of the Mount Trust, the Floyd and Josephine Segel Collection, and gifted by Florence and Herbert Irving to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, that later sold in these rooms, 10th September 2019, lot 17, and is published in Roger Keverne, ed., Jade, London, 1995, pl. 41. Another related, smaller example, lacking an inscription, from the William Boyce Thompson Collection, was sold in these rooms, 23rd September 2020, lot 65. A similar jade boulder depicting the second luohan, Kanakavasta, accompanied by two imperial colophons and seals from the collection of the Wou Lien-Pai Museum and published in Rose Kerr et al., Chinese Antiquities from the Wou Kiuan Collection, Surrey, 2011, pl. 177, was sold in these rooms, 20th March 2021, lot 24. A white jade boulder carving of a seated luohan also bearing an inscription, from the De An Tang Collection, was sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 13th October 2021, lot 3622.