Arts of the Islamic World & India including Fine Rugs and Carpets

Arts of the Islamic World & India including Fine Rugs and Carpets

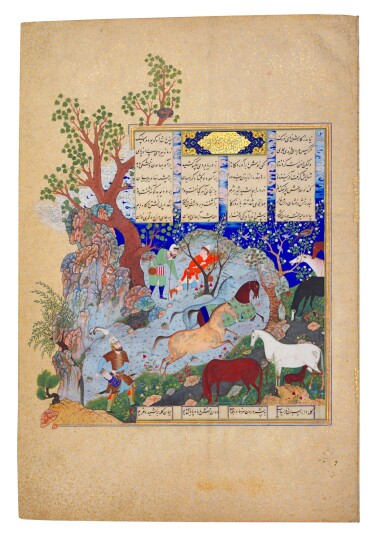

Rustam recovers Rakhsh from Afrasiyab's herd, illustrated folio (f.295r.) from The Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, attributed to Mirza 'Ali, Persia, Tabriz, Royal Atelier, circa 1525-35

Auction Closed

October 26, 12:30 PM GMT

Estimate

4,000,000 - 6,000,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

gouache and ink heightened with gold on paper, text written in four columns of fine nasta'liq script with illuminated heading, double intercolumnar rules in gold, wide gold-sprinkled margins, verso with 20 lines to the page in black nasta'liq arranged in four columns with an illuminated heading and illuminated panels, catchword lower left

painting: 34.3 by 28cm.

leaf: 47 by 31.7cm.

Commissioned by the Safavid Emperor Shah Isma'il, circa 1522.

Completed under the patronage of his son Shah Tahmasp at the royal atelier,

Tabriz, circa 1525-40.

Presented in 1568 by Shah Tahmasp to the Ottoman Sultan Selim II (r.1566-74).

In the collection of Baron Edmund de Rothschild, Paris, 1903-34.

By Descent to Baron Maurice de Rothschild, Paris, 1934-57.

His estate 1957-59.

Arthur A. Houghton Jr., USA, 1959-88.

Christie's London, 11 October 1988, lot 4.

Private collection, Europe.

S.C. Welch, Wonders of the Age, The British Library, London; The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1979-80, p.88-89, no.26.

M.B. Dickson & S.C. Welch, The Houghton Shahnameh, Cambridge, Mass., and London, Harvard University Press, 1981, vol.II, pl.169.

D. Davis (tr.), Stories from the Shahnameh of Firdausi, Washington D.C., 2005, pp.128-9 and 304.

S.R. Canby, The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2011, pp.189 and 285.

The Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Arts, Tehran, 2021, p.185.

Wonders of the Age, The British Library, London; The National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1979-80.

The Shahnameh or 'Book of Kings' is the Persian national epic, telling the history and legends of Persia from prehistoric times down to the end of the Sassanian dynasty in the seventh century AD. The author, Firdausi (circa 933-1020), assumed the task of writing the history of the Persian kings in verse in 976 after Dakiki, a poet friend who had started the work, was murdered, Firdausi devoted the remainder of his working life to composing the 30,000 couplets of the Shahnameh. The finished text was presented to Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna in 1010. The text was henceforth to become a touchstone of Iranian royalty, the text which, above all others, was to be revered by kings as confirmation of their sovereignty and as a symbol of their dynastic legitimacy. From the fourteenth century onwards no cultured prince could ignore the obligation to commission his own illustrated version of the national epic.

This folio belongs to the famous copy of the Shahnameh commissioned by Shah Isma'il I (r.1502-24), the first Safavid Shah of Iran and completed by his eldest son Shah Tahmasp I (r.1524-76). Shah Isma'il was a dynamic, charismatic and powerful character who conquered the ruling Aq-Qoyunlu Turkman and Uzbek tribes, creating an empire which encompassed a vast area from the Caucasus in the north-west to the Oxus river in the east and the shores of the Arabian Sea in the south. The new empire took in the most important cultural cities of the region - Herat, Shiraz, Qazwin and Tabriz, making the latter the new Safavid capital. By 1522, the probable date of commissioning of the manuscript, Shah Isma'il had completed his conquests and was becoming interested in the arts. Shah Tahmasp, as a boy only eight years of age, had just returned to his father's capital from Herat where he had been child governor. Shah Isma'il died in 1524, respected and revered by the entire court, and Shah Tahmasp continued his father's passion for the arts of the book and specifically the production of this monumental copy of the Shahnameh, devoting the royal atelier to its preparation and production for a period of nearly two decades. Probably no other Persian work of art, save architecture, has involved such enormous expense or taken so much artists' time.

The Shahnameh has no colophon, and the only date is inscribed on one of the miniatures – 934 AH/1527-28 AD, but the illuminated dedication on folio 16 states definitely that the manuscript was made for the library of Shah Tahmasp. A second manuscript prepared for Shah Tahmasp is the Khamsa of Nizami, now in the British Library, London (Or.2265). The Khamsa is of similar dimensions to the Shahnameh and is usually regarded as its sister manuscript. In its present condition it contains fourteen contemporary illustrations, painted within a shorter period circa 1539-43, thus representing the Tabriz style in its full maturity. With their contemporary inscriptions and attributions, the miniatures of the Khamsa provide a basis for comparison and attribution of the Shahnameh miniatures.

The current folio illustrates the scene in which Rustam discovers his horse Rakhsh amongst Afrasiyab’s herd. The illustration depicts Rustam dressed in his leopard-skin cap, securing Rakhsh whilst also releasing the royal stud much to the surprise of the royal herdsmen. Rustam was given Rakhsh, the handsome chestnut steed, by his father Zal who had promised to find him a horse worthy of his warrior status. Rakhsh (Persian for ‘lightning’) was selected from all the horses that roamed Zabulistan and Kabulistan and was famed for his speed and spirit. According to Rustam “Its body was a wonder to behold, Like saffron petals, mottled red and gold; Brave as a lion, a camel for its height, An elephant in massive strength and might”

Shah Isma'il's conquests of different regions and cultural centres had enabled him to gather artists of different training and experience. It was this composite nature of the atelier that led to a new and glorious hybrid style of Persian miniature painting, now known as the Tabriz style. In his extensive research into this manuscript and early Safavid painting, Stuart Cary Welch identified two main source styles: the Timurid tradition of Herat and the Turkman tradition of Shiraz and other centres. At Shah Tahmasp's atelier older masters worked side by side with younger artists, encouraging the development of individual artists' skills and enhancing the performance of the atelier as a whole. The manuscript displays the remarkable range of Persian miniature painting of the period, all of an extraordinarily high standard.

Sultan Muhammad was the first leading artist of the Shahnameh, and the one to whom much of the initial stylistic innovation is credited. It appears that for a middle period the leadership was taken over by Mir Musavvir, and that towards the end it was Aqa Mirak. It is believed that the atelier must have occupied at least fifteen painters, identified as separate hands by Welch.

Mirza ‘Ali was the son of Sultan Muhammad and thus belonged to the second generation of painters working on the Shahnameh. He grew up in the royal atelier and was a pupil of Bihzad and Aqa Mirak, becoming a leading artist of his generation. This illustration is one of the six miniatures in the Shahnameh that Welch has attributed to Mirza ‘Ali. Welch’s attribution is based largely on comparisons with Mirza ‘Ali’s signed miniatures in the British Library's Khamsa. According to Welch this illustration is an unusual scene for Mirza 'Ali, as the artist favoured indoor figural settings. However here the artist has created an outdoor scene that displays an acute sensitivity to nature. His bold colourful composition is skillfully balanced; the movement of the fleeing horses in the lower right offset by the large sinuous tree stretching its branches beyond the confines of the upper left margins. The fantastical rocky outcrops and scrolling cloud bands are delicately rendered and pay homage to his father’s Gayumars masterpiece (now in the Aga Khan Museum, Toronto). The inclusion of a fledglings nest within the upper branches and the personalisation of the faces of the figures and horses demonstrates the artists creativity and attention to detail. A jewel-like quality is achieved in the exquisite depiction of the caparisoned horse and Rustam's beautifully embroidered quiver. This miniature is not just an illustration to the narrative but a spiritual depiction of man, animal and nature.

After about 1540 Shah Tahmasp's interest in the arts waned, he became increasingly religious and was weighed down with political concerns. The threat of invasion by the Turks from the west had been a recurrent problem, settled by treaty in 1555. When Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent died in Hungary in 1566, there were fears in Tabriz that the treaty might not be upheld by his successor Sultan Selim II (r.1566-74). In 1567 a Safavid embassy led by Shah Quli left for Turkey and met with the Sultan at Edirne in February of 1568. The pomp of the occasion was noted by the Hapsburg embassy, then also present at the Ottoman court. There were thirty-four camels bearing the most magnificent gifts from Shah Tahmasp to the new Sultan. Top of the list of gifts and thus rated the most valuable, were two manuscripts, one a copy of the Qur'an said to have been written by the Imam Ali himself, the other a Shahnameh. Records show that this was indeed Shah Tahmasp's great volume. The Shahnameh stayed with the Ottomans for over three centuries, preserved in almost miraculous condition. Unlike the miniatures of so many Persian manuscripts, the compositions of the Shahnameh illustrations were not generally used or echoed in subsequent manuscripts. This could be partly because of their size and complexity, but also because the volume left Persia so soon, later artists had little access to it.

The manuscript left Istanbul about the end of the nineteenth century and reached France. By 1903 it was in the collection of Baron Edmond de Rothschild who lent it for exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, where the catalogue description gave no hint of its magnificence. It was probably MS.17 in the Rothschild Library. It passed to Maurice de Rothschild in 1934 and after his death in 1957 it was one of a number of outstanding Rothschild books offered for sale, principally in America.

It was acquired by the collector and bibliophile Arthur A. Houghton Jr., benefactor of the Houghton Library at Harvard University. The volume was disbound so that separate pages could be exhibited - at the Grolier Club, the Pierpont Morgan Library and elsewhere. In 1971, 76 folios with 78 of the 258 illustrations were transferred to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Further dispersals occurred over the next two decades, and in addition to those in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there are leaves of Shah Tahmasp's Shahnameh in the Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin; The Freer/Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the David Collection, Copenhagen; the Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia; the Aga Khan Museum, Toronto; the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha; the Nasser D. Khalili Collection; Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Cambridge, Mass., and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tehran.

In Stuart Cary Welch's personal handwritten list of 'Outstanding Pictures Painted for Shah Tahmasp's Shahnameh', which includes only fifty out of the two hundred and fifty-eight illustrations, he gives the present painting four out of a possible five stars.