Arts of the Islamic World & India including Fine Rugs and Carpets

Arts of the Islamic World & India including Fine Rugs and Carpets

Property from the Collection of Betsy Salinger

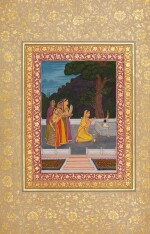

Ladies Worshipping a Lingam, India, Provincial Mughal, Lucknow, circa 1760-70

Auction Closed

October 26, 12:30 PM GMT

Estimate

7,000 - 10,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

gouache heightened with gold on paper, pink and orange borders with gold floral vine, black and coloured rules, buff margins with a gold arabesque issuing lotus palmettes and scrolling tendrils, nasta'liq calligraphy on the reverse, with illumination in colours and gold

painting: 18.4 by 12.7cm.

leaf: 40.64 by 26.7cm.

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE COLLECTION OF BETSY SALINGER

My introduction to the captivating world of Indian miniature paintings was absolutely unplanned and unexpected. In 1980, I happened to enter the exhibition rooms at Sotheby’s, New York, and homed in on an otherworldly picture of a variety of creatures in a nighttime landscape, some the targets of arrows launched by hunters clad in green leaf skirts, whose bows were flexed and taut. Thatched huts and smoldering camp fires dotted the landscape. A dragon-like creature bellowed flames into the air, and in the foreground a variety of forest animals performed the drama of their nightly activities. I knew nothing about this type of painting except that I was smitten.

I was drawn into a magical universe of a centuries old painting tradition brimming with saturated color, mastery of line and form, stylistic differences, and an unimpeachable approach to constructing a scene. Then there are the details: the mastery of the brush in depicting a hairline or a hand; the splendid presentation of a highly decorated vina; the countless, crisp blossoms of a tree; the tiniest of perfectly rendered jewels; the expert and meticulous modeling and execution of the human form; the complex patterning of a patka or a turban; a barely perceptible slipper edged with the thinnest line of gold; the meticulous attention paid to the intricate, minute floral design of a carpet, to facial expressions and type, to the fluttering hem of an attendant's dress, to the facade and curtains of an outdoor pavilion. I quickly realized that the more deeply I looked at a painting, whether with a magnifying glass or without, the more rewarded I was. As my interest grew, so did my visits to museums, galleries, and auction houses, and I began reading more and more on the subject, which further enhanced my understanding and appreciation. Here too, the deeper I looked (or studied) the more I was rewarded.

Apart from their beauty, Indian miniature paintings are endlessly interesting and emotive – works which beg us to immerse ourselves in an art form teeming with content and the power to move us on a visceral level. From outstanding Mughal folios to the distinctive styles of the lyrical Pahari schools; from the dynamic and varied Rajasthani schools to the masterful Provincial Mughal and Deccani schools and court ateliers; crossing centuries, at times borrowing artistic traditions from near and far away lands, Indian miniature paintings occupy a world of vivid imagery, technical refinement, seductive subject matter, and artistic imagination. I am forever amazed and enthralled at how deftly an artist can put so much- with such clarity and skill, capturing the soul of the viewer, our eyes wide open with wonder and marvel, our hearts skipping a beat or two- onto a sheet of paper so small.

Betsy Salinger, July 2022.

THE PRESENT LOT

This charming painting depicts a maiden kneeling on a terrace at night before a lingam shrine illuminated by candlelight with four female companions standing behind her. A painting by Fateh Chand circa 1735 in the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum in Jaipur has an almost identical composition (see Randhawa and Galbraith 1968, p.10). Both paintings are an illustration to a ragamala series and represent Bhairavi ragini, and are closely comparable to a signed ragamala illustration by Fateh Chand in the Victoria & Albert Museum, dated to circa 1760-70, Lucknow (IS.42-1996) and another from the Johnson album in the British Library (see Falk & Archer 1981, p.124, no.202). Interestingly both our example and the ragamala illustration in the Victoria & Albert Museum have identical gold arabesque margins.

The calligrapher of the Persian quatrain on the reverse of the album page can be identified as Hafiz Nurullah. He is recorded as having served at the court of Asaf al-Dawla of Awadh (r.1775-97) in Lucknow. Ghulam Muhammad Dihlavi praised him in his tadhkira as a person and his nasta’liq hand in both small and large in ‘Abd al-Rashid Daylami’s style (M. Hidayat Husain (Ed.), The tadhkira-i-khushnavisan of Mawlana Ghulam Muhammad Dihlavi, Calcutta, 1910, pp.64-65). Bayani records five works by him, two dated 1153 AH/1740-41 AD and 1154 AH/1741-42 AD (Mehdi Bayani, ahval va athar-e khosh-nevisan, vol.3, Tehran, 1348, p.949). Further examples of his hand were mounted on Lucknow albums of the 1770s and 1780s, including other folios from the present album (see Sotheby's London, 14 December 1987, lots 26, 27, 28, 31, 35, 40; 19 October 2016, lot 18) and folios from the Polier Album (8 October 2014, lots 270-2).