The Scholar's Feast: The Rosman Rubel Collection

The Scholar's Feast: The Rosman Rubel Collection

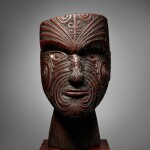

Maori Head, New Zealand

Lot Closed

April 8, 04:39 PM GMT

Estimate

30,000 - 50,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Maori Head

New Zealand

upoko whakairo

Height: 8 ⅞ in (22.5 cm)

Harry G. Beasley, Chislehurst, acquired from the above in 1919 (inv. no. 29-3 1098)

Irene M. Beasley, Brighton, by descent from the above

Merton D. Simpson, New York, acquired from the above in 1964

Mark Eglinton, New York, acquired from the above

Abraham Rosman and Paula Rubel, New York, acquired from the above in 2007

This carved head, or upoko whakairo, was once owned by Harry Geoffrey Beasley (1881-1939), the well-known English collector. Beasley acquired the head in 1919 from Fenton and Sons, the London dealers, and recorded the acquisition in his ledger with the following description: “A wooden head of hard yew wood bearing elaborate moko. The whole is doubtless intended to be a substitute for a dried head. The work on the face is steel cut. 9 1/8 inches long. Said to be called RAHUI.” (Beasley’s ledgers, Anthropology Library and Research Centre, British Museum, London).

Rahui is an important concept in Maori culture; a simple definition is that rahui is a “mark to warn people against trespassing; used in the case of tapu […]” (Williams, Dictionary of the Maori Language, Wellington, 1971, p. 321). Presumably this was how Beasley understood the term and in a rather testy letter to the Journal of the Polynesian Society, he writes that he is aware of carved heads described as “‘Taboo’ [tapu] marks, notably one in the British Museum” (Beasley, “Notes and Queries. 441, Carved Maori Artifacts”, Journal of the Polynesian Society, Vol. 38, No. 4, December, 1929, p. 291). Beasley then suggests that a head in his collection “obviously represents a portrait […of] a mokoed […] head, which for some reason or other has been lost to the owner’s family. It is common knowledge that these were highly valued […]” (ibid.). He also notes that his portrait theory can be equally applied to “two others known to me.” (ibid.). We know that by 1929 Beasley’s collection contained three carved Maori heads, including the present lot. It is reasonable to suppose that it may be one of the three that he refers to (the head discussed and illustrated in the letter is now in the British Museum, London, inv. no. 1944 OC.2.807; the third head is in the Musée des beaux-arts, Montreal, inv. no. 1958.Pc.4).

As his ledger suggests, Beasley understood the present sculpture as a replacement for a lost mokomokai, or toi moko, the precious preserved head of an ancestor. He also presumably took it to be a portrait, just as he did the head mentioned in his letter to the JPS. The editors’ reply dismissed Beasley’s theory, summarily noting that “We do not know that the Maori carved such objects to serve as ‘portraits’ of his friends, and so preserved them as we preserve a photograph, but the Maori did carve out such heads and use them for a purpose not mentioned by our correspondent. The ruru, koruru, or parata is such a carved head [...]” (ibid.). The editors of the JPS overlooked the three self-portrait heads carved by the famous Ngapuhi rangatira, or chief, Hongi Hika (c. 1772 – 1828), during his 1814 visit to Sydney. The portraits were carved at the request of the Reverend Samuel Marsden, who wrote, “I told [Hongi Hika] one day, I wanted his head to send to England; and that he must either give me his head, or make one like it of wood.” (Marsden in Church Missionary Society, ed., The Missionary Register for the Year 1815 [...], Vol. III, London, 1815, p. 198). As Crispin Howarth notes, this was presumably “gallows humour, and the acceptance by Hika of what would otherwise be an outrageous remark may underline a strong bond between these two men.” (Howarth, “From the Chisel of Mataora: The Maori Art of Skin Marking”, Tribal Art Magazine, No. 91, Spring 2019, p. 76; the article illustrates the Hongi Hika self-portrait now in the Macleay Museum, Sydney, inv. no. ETI.570).

Of course, the editors of the JPS were correct to point out that Maori made many carved heads, such as the koruru or parata, gable masks which were placed at the apex of the wharenui, or meeting house. The head discussed in Beasley’s letter might fit such a purpose, and the late David Simmons more recently described it as a “mask for under a trapezoid [canoe] prow” (Starzecka, Neich, and Pendergrast, The Maori Collections of the British Museum, London, 2010, p. 72). The present lot, however, is an object that defies easy categorisation. It cannot be conceived of us as a koruru, and although it could have come from a post figure, or pou tokomanawa, it does not appear to have been cut from a larger, complete figure, but instead carved within the peculiar limits of the available piece of wood. This is perhaps most notable in how the moko, or skin markings, are adapted to the form of the head so that, without being absolutely symmetrical, both sides of the forehead mirror each other. The moko also runs just into the head's top edge, and there is no evidence of an abrupt cut disrupting the pattern. The present sculpture has a full face, or moko kanohi of male moko. Moko was "a symbol of birthright, of recognized hereditary status, or it was earned as a privilege gained by deeds that brought great spiritual mana [...] moko not only shows a person's individual traits but also is a mark of society, a connection to a person's clan, or hapu, and a connection to their greater tribal community, iwi. Reading its markings allows others to visibly understand the wearer's standing in life." (Howarth, ibid., pp. 75-76).

Perhaps the present sculpture is best understood as an example of what the great Roger Neich called “metonymical portraiture”. Neich wrote that “Maori carving portraiture could be called metonymical in that a characteristic part of the individual was used to signify the whole person. This part could be a tattoo pattern known to belong to that individual, a well-known attribute such as a type of weapon, or a famous incident in which the individual participated. Metonymical portraiture especially suited a situation where the physiognomy of the individual being depicted was not known […] But even where the individuals depicted were only recently dead or occasionally still living, conventionalised metonymical portraiture predominated. […] However ancestors and other individuals were represented, their presence in a composition was important not only for their own sakes, but even more so for the statements the composition made about the relationships between them and their descendants.” (Neich, Carved Histories: Rotorua Ngati Tarawhai Woodcarving, Auckland, 2001, p. 135).