The Passion of American Collectors: Property of Barbara and Ira Lipman | Highly Important Printed and Manuscript Americana

The Passion of American Collectors: Property of Barbara and Ira Lipman | Highly Important Printed and Manuscript Americana

Hamilton, Alexander | Scarce first edition of the notorious "Reynolds pamphlet"

Auction Closed

April 14, 05:34 PM GMT

Estimate

18,000 - 25,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Hamilton, Alexander

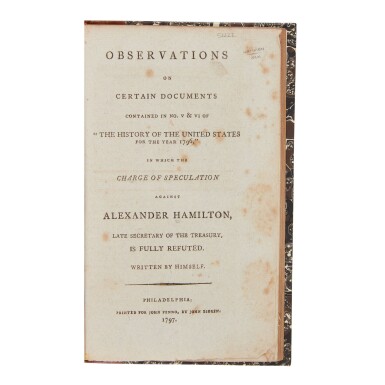

Observations on Certain Documents contained in No. V & VI of "The History of the United States for the Year 1796," in which the Charge of Speculation against Alexander Hamilton, late Secretary of the Treasury, is Fully Refuted. Written by Himself. Philadelphia: Printed for John Fenno, by John Bioren, 1797

8vo in half-sheets (208 x 126 mm), printed on pale blue paper; light browning, some scattered foxing, chiefly marginal. Half brown calf over marbled boards, red morocco spine label.

First edition of the notorious "Reynolds pamphlet." In the summer of 1791, twenty-three-year-old Maria Reynolds called on Hamilton at his Philadelphia residence, claiming that her husband had abandoned her and that she hoped that Hamilton, as a fellow New Yorker, would be willing to help her relocate to that city. (Hamilton’s family was at Albany at the time, with Elizabeth’s parents.) Hamilton agreed to see Mrs. Reynolds that evening, and it soon became clear, as Hamilton later wrote in the ''Reynolds Pamphlet,'' that something ''other than pecuniary consolation would be acceptable'' to Mrs. Reynolds. And, so, the young woman became his mistress. The affair continued into December, when Hamilton received a letter from James Reynolds (who may have been conspiring with his wife all along) stating that he knew about the affair, could no longer live with his wife because of it, and proposing that Hamilton pay him $1,000 to quit Philadelphia, leaving his wife for Hamilton to do with as he thought proper. Hamilton paid the blackmail and—incredibly—continued the affair. James Reynolds, however, did not leave town, and he continued to solicit and receive smaller payments from Hamilton after each assignation.

In November 1792, Reynolds, who had been involved in dubious financial dealings with Revolutionary War pensions, was imprisoned for forgery. When Hamilton ignored his plea for help, Reynolds instead sought a meeting with his Democratic-Republican rivals, including James Monroe, claiming that Hamilton had instigated an affair with his wife and been engaged in illegal speculation while Secretary of the Treasury. When confronted, Hamilton told his political enemies of Reynolds’s blackmail scheme, and while he admitted, as he was later to write in this pamphlet, that he was guilty of an ''irregular and indelicate amour,'' he was able to convince them that he had not been involved in speculation. Hamilton seems to have finally ended his relationship with Maria Reynolds at this point (she remarried in 1795), and there the entire episode might have terminated, but for three things: James Monroe had made copies of the correspondence between Hamilton and the Reynoldses; Monroe sent copies of the letters to Thomas Jefferson; and Hamilton continued to attack Jefferson’s public policies and personal conduct.

So it was that in the summer of 1797 the affair and the accusation of speculation came to public notice in two scorching pamphlets by James Callendar, subsequently collected in The History of the United States for 1796; Including a Variety of Interesting Particulars Relative to the Federal Government Previous to That Period (Philadelphia, 1797). Facing ruin, Hamilton responded by issuing this extraordinary pamphlet, in which he fully admitted to the affair with Maria Reynolds but disproved the charge of financial impropriety. While the Hamilton’s marriage survived the Reynolds affair and while his public life continued, the scandal ended any possibility of Hamilton winning an elective office.

This first edition is very uncommon since Hamilton's family attempted to find and destroy as many copies as they could. The pamphlet proved so damaging to the author's reputation that it was reprinted by his anti-Federalist opponents in 1800.

REFERENCE

Celebration of My Country 138; ESTC W21303; Evans 32222; Federal Hundred 68; Ford, Bibliotheca Hamiltoniana 64; Howes H120; Sabin 29970; cf. Syrett, "Introductory Note: From Oliver Wolcott, Junior," in Papers of Alexander Hamilton 21:121–144