La Trame du Rêve : l’Art du Textile en Asie du Sud-Est

La Trame du Rêve : l’Art du Textile en Asie du Sud-Est

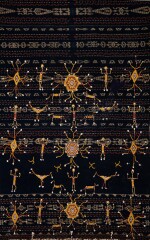

Jupe cérémonielle de femme lawo butu, Kabupaten de Ngada, Florès, Petites îles de la Sonde, Indonésie, 19e siècle | Woman’s ceremonial tubular skirt sarong lawo butu, Ngada people, Flores, Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia, 19th century

Lot Closed

April 9, 12:18 PM GMT

Estimate

12,000 - 18,000 EUR

Lot Details

Description

Jupe cérémonielle de femme lawo butu, Kabupaten de Ngada, Florès, Petites îles de la Sonde, Indonésie, 19e siècle

74 x 146,5 cm ; 29 x 57 4/6 in

Collection privée, Suisse, avant 1980

Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis (prêt long terme)

Adams, Threads of Life A Private Collection of Textiles from Indonesia and Sarawak, The Katonah Gallery, 1981 : n.p., fig. 3.

The Katonah Gallery, Westchester, Threads of Life A Private Collection of Textiles from Indonesia and Sarawak, 7 juin-26 juillet 1981, n° 24

Richesse matérielle et richesse rituelle – le textile se conçoit en Indonésie comme un élément souverain, à la croisée du terrestre et du spirituel, présent dans toutes les strates de sociétés structurées par un système hiérarchique millénaire. Véritable marqueur économique et social, le tissu opère une subtile distinction visuelle entre les âges, les genres, les classes sociales.

Ce langage particulier de l’étoffe – symboliquement exprimé dans la composition décorative, l’élection de tel ou tel matériau, le rejet d’une forme au profit d’une autre – se fait plus fin et vibrant encore dans le cadre des rites cérémoniels qui rythment l’existence des habitants de la région.

Affectant la forme tubulaire particulièrement courante du sarong, commune au vestiaire féminin et masculin, cette jupe cérémonielle se détache pourtant du reste du corpus comme un exemplaire prodigieux de beauté et de maîtrise, rendu plus rare encore par la quasi-disparition, de nos jours, de cette production particulière.

Dans le monde indonésien, où le travail textile est une activité strictement féminine, inscrite dans un système parfaitement réglé et prédéfini de rites de passages, ces sarongs possèdent un caractère unique matérialisant la rencontre créatrice des mondes masculins et féminins. Aux femmes sont ainsi dévolus les travaux traditionnels de tissage et de teinture tandis que les hommes se chargent de concevoir et broder les minutieux motifs perlés.

Qualité de la teinture, finesse de l’ornementation perlée, virtuosité du travail du tissage…ce chef d’œuvre de prouesse technique et esthétique se mesure ainsi à l’aune de la rareté des réalisations de ce type.

Dits lawo butu, ces sarongs n’étaient portés par les femmes du peuple Ngada, des îles Florès, qu’à l’occasion des rites cérémoniels les plus importants, notamment lors de la bénédiction d’une nouvelle maison du clan ou l’édification d’un autel aux ancêtres. Reflet de leur valeur, ils étaient exclusivement revêtus par les femmes les plus âgées du clan et commandés, par les chefs, auprès des tisserandes les plus talentueuses. Lorsqu’ils n’étaient pas portés, les sarong lawo butu étaient conservés, avec le reste des trésors, dans la maison du clan. A la mort de leur propriétaire, par le biais d’une singulière analogie, ils prenaient le nom de celle qui les avaient portés d’où le terme de lawo ngaza « jupe avec un nom », qui les désigne parfois.

Les motifs de perles de cet exemplaire affectant la forme d’humains et d’animaux stylisés présentent d’indéniables similitudes avec le lawo butu actuellement conservé au Met et ancien joyau de la collection Robert J. Holmgren and Anita E. Spertus.

Material prosperity and ritual wealth – textile, in Indonesia, is a paramount element, at the crossroads of earthly and spiritual worlds, found in every strata of societies deeply structured by a thousand-year-old hierarchical system. Behaving as a true social and economic marker, textile is a subtle and visual distinction between age, gender and social classes. Fabric seems to possess a language of its own – reflected in the decorative arrangement, the adoption of a particular material, the selection of a certain form over another – a language that takes on a renewed elegance and vibrancy when it is at the center of the ceremonial rites punctuating the lives of the people of the region.

With its highly basic tubular shape – the one of sarong – worn by both men and women, this ceremonial skirt manages to still stands out from the rest of the corpus as a remarkable object, of equal beauty and brilliance, made even the rarer by the near-extinction, these days, of this specific production.

In the Indonesian world, where textile work is an activity strictly limited to women, embedded in a predefined system of rites of passage, those sarongs possess a unique nature, embodying the creative meeting of male and female worlds. As women weave and dye, in a most traditional way, men are tasked with the pearl embroidery work.

The excellence of the dyeing process, the beautiful rendering of the beadwork, the mastery of the weaving work…this masterpiece of technical and esthetic prowess adds rarity to beauty.

Called lawo butu, those sarongs were only worn by the Ngada women, of Flores island, for the most prominent ceremonial rites, such as the blessing of a new house or when building a shrine for the ancestors. So grand were their value that they were the result of a commission from the chief to the most talented weavers and only the oldest women of the clan could wear them. Outside of the ceremonies, the lawo butu sarong were kept, along with the rest of the family treasures and heirlooms, in the clan house. After the passing of their own, through a peculiar analogy, they took on the name of their former wearer hence why they are sometimes referred to as lawo ngaza “named skirt”.

The stunning beadwork in the stylized shapes of humans and animal is not unlike the one adorning the lawo butu now in the Met and former jewel of Robert J. Holmgren and Anita E. Spertus Collection.