Auctions

Buy Now

Collectibles & More

Books & Manuscripts

Fine Books and Manuscripts

Fine Books and Manuscripts

Lot Closed

July 16, 06:36 PM GMT

Estimate

12,000 - 18,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Bukowski, Charles

Archive of correspondence addressed to Kay "Kaja" Johnson, Los Angeles, California: July – November 1961

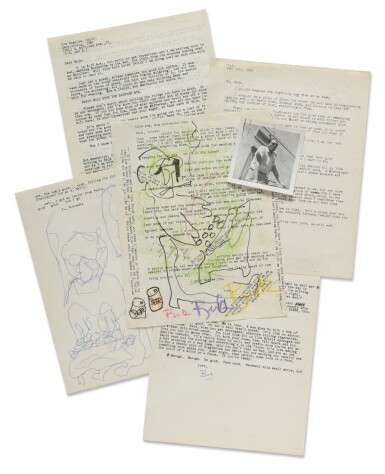

3 typed letters and 10 typed letters signed "Buk," "Bukowski," and "Buk Buk Buk" (approximately 276 x 215 mm), overall 24 pages with multiple manuscript emendations in different types of ink and crayon, 5 sketches, 1 black and white photograph of Bukowski, and 1 typed envelope; occasional light soiling, rust where previously paper clipped, previously folded as expected.

"Each poem, I think, should be as close to a suicide note as possible, saying what the mind must say and why" — A fine group of early letters from the laureate of American lowlife

After publishing a handful of stories in the mid-forties, Charles Bukowski grew disillusioned with the literary world, and descended into a decade of heavy drinking, what he would later call his "lost years." This period was punctuated by painful physical ailments, including a life-threatening bleeding ulcer. This correspondence finds our author at the cusp of a newly productive period — working at the Los Angeles Post Office, and reengaging with an assortment of alternative literary magazines. In this wide ranging correspondence with artist and fellow poet Kay "Kaja" Johnson, Bukowski discusses his literary endeavors, the indulgences and miseries of daily life, suicidal ideation, his job at the Post Office, but above all he reflects on their shared preoccupation: poetry.

Bukowski addresses his literary fore-bearers head on, including Hemingway, ("I said Hemingway was spelled with one M. Why do you insist on 2? You are making him 2twice as heavy and he was overrated as it is ... although all this does not include the very great book his only one A FAREWELL TO ARMS") and Henry Miller ("I think a person like Henry Miller ... wanted too badly to become famous, wanted this more than the flow. He got his fame, and that’s all it is: coins and carvings of fame; the light is out of his face, all the wires are cut...").

Fame and recognition are clearly on the author's mind, and they continue to be discussed in his characteristically irreverent manner. During his lost years, he tells Kaja that drinking was his poetry, he would "fall acroos the rug drunk and beat my hands on the rug and scream, I AM A GODDAMN GENIUS AND NOBODY KNOWS IT BUT I" for the amusement of a companion. Drunken outbursts aside, he speaks more candidly about his literary standing in America, going on to say: "I am glad the usa ignores me. Fame is bad, Kaja. I can think of very few people who remained as they were before fame. I think god, any god, who has saved me from this thing."

These reflections on literary fame come on the heels of the publication of the author's first chapbook of poems in October 1960 — Flower, Fist and Bestial Wail — and the impending publication of his second. He relays to Kaja that while he doesn't paint much anymore he "did the cover (covers) for [his] next book of pomes." In his letter of November 7, he tells Kaja "My latest book is out (ha, ha, I can say latest now because this makes 2), LONGSHOT POMES FOR BROKE PLAYERS, from 7 Poets Press." Throughout this archive, he also refers to his work with Jon Edgar Webb and The Outsider, Targets, and assorted other small literary magazines (Quicksilver, Satis, and more) in addition to referencing Carl Larsen (who acted as editor for Longshot Pomes..."), Caresse Crosby and the Black Sun Press, Sheri Martinelli, and others.

Bukowski repeatedly muses on the nature of poetry, ("Poetry has been too much the exclusive territory of the wise who have turned out to be not so wise after all. Who wants to hear a rhyming pome when he is poised on the top of a building? Or a criticism of Keats? ... Each poem, I think, should be as close to a suicide note as possible, saying what the mind must say and why, and this doesn’t mean you can’t laugh or relax and that it must be right ON POINT, but, god damn it, why are we wasting so much time saying nothing?"), while elsewhere his daily observations verge on the poetic ("[Sometimes] I lift a tall can of beer and the coldness touches my insides and nobody is bothering with me. There Hemingway has gone down under the shotgun and I am standing in a dirty kitchen alive. This is important: standing in a dirty kitchen alive.")

Kaja was an established poet in her own right, and Bukowski praises her writing in his letter of July 28, telling her, "I told Jon [Webb] I thought your poem in OUTSIDER #1 one of the best, which it was, saying the odd things." When their correspondence picks up, Kaja is living in New Orleans, and Bukowski attempts to put her in touch with the writer John William Corrington, then teaching at LSU. Bukoswki's letter of "August 14, I think" references an impending move ("Are you going to France or New York? or Los Angeles? or where?") Followed by confirmation shortly thereafter ("I now have 2 letters from france and one from england. someday, they say, I will get a letter from hell").

In Paris, Kaja took up residence at the so-called Beat Hotel on 9 Rue Gît-le-Cœur in the Latin Quarter. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the heretofore rundown and unnamed hotel became a haven for artists, writers, poets, and musicians, including some of the biggest names of the Beat movement: Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, William S. Burroughs, and Gregory Corso. While there are relatively few details of Kaja's life available, the photographer Harold Chapman spoke later about an encounter between the two at the Beat Hotel, which illustrates a certain shared sensibility with Bukowski: "I was fast asleep at about 2 am when a knock on my door awakened me. On opening the door, there was a picture of Kaja looking very rough and absolutely out of it. She mumbled, 'Would you like to take a photograph of suffering?' 'Yes,' I said, ushering her into my room and reaching for my camera, always ready and set ... this image is probably the most striking shot that I took in the Beat Hotel."