Making Our Nation: Constitutions and Related Documents. Sold to Benefit the Dorothy Tapper Goldman Foundation. Part 1

Making Our Nation: Constitutions and Related Documents. Sold to Benefit the Dorothy Tapper Goldman Foundation. Part 1

United States House of Representatives (Bill of Rights) | The first separate printing of the Bill of Rights

Auction Closed

November 23, 05:04 PM GMT

Estimate

700,000 - 1,000,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

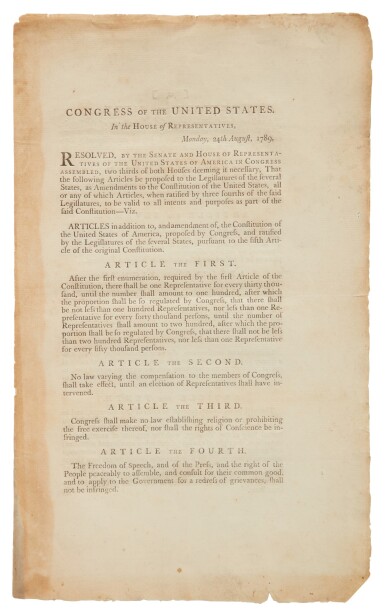

United States House of Representatives (Bill of Rights)

Congress of the United States. In the House of Representatives, Monday, 24th August, 1789, Resolved … That the following Articles be proposed to the Legislatures of the several States, as Amendments to the Constitution of the United States. New-York: T[homas]. Greenleaf, near the Coffee-House, [1789]

3 pages (342 x 210 mm) on a bifolium of laid paper (watermarked sh) now separated at central fold; some marginal browning, a few short marginal tears, first leaf neatly reinforced at left margin. Blue cloth folding-case, chemise, the box and chemise both with blue morocco labels, the inside cover of the box signed by Supreme Court Justices Sandra Day O’Connor, Stephen Breyer, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The first separate printing of the amendments that became the Bill of Rights and the earliest printed version to enumerate the proposed amendments as clearly defined articles: a foundational document of the United States on a par with the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

"When the first Congress, along with President George Washington, gathered in New York City in 1789, Americans did not assume that the process of constitution-making was now—or ever would be—complete. Many expected the document to be amended almost immediately. Several state conventions had ratified the Constitution with the expectation that their suggestions for its improvement would be taken up and adopted. Most of the proposed amendments grew out of one of the main critiques that Antifederalists such as the Pennsylvania addressers had leveled against the Constitution: that it lacked a bill of rights resembling those attached to most state constitutions. Americans strongly desired guarantees that the federal government would not use its considerable powers to infringe key individual rights. … The Philadelphia convention may not have given much thought to a bill of rights, but it had provided a method by which Americans could add one. Article V of the Constitution outlined the procedure for amending the nation's fundamental law" (CCC, pp. 81–82).

There was no shortage of suggestions as to what a bill of rights should contain. In addition to the provisions of the various state declarations of rights, the ratifying conventions put forth a substantial number of proposals, ranging from South Carolina's four to New York's fifty-seven.

On 4 May 1789, James Madison proposed in the House of Representatives that debate begin on a series of amendments to the Constitution to serve as a bill of rights. Debate began on 8 June and was then referred to a select committee of eleven which, under the close guidance of Madison, created an initial draft that was presented to the House on 28 July. Unlike the present document, that draft was presented as revisions to the text of the Constitution itself, a confusing and ambiguous method that diluted the committee's charge: creating a clearly defined set of rights to be enshrined under the protection of the United States Constitution. The purpose of the present document of 24 August is clearly stated and the text is so formatted: "Articles in addition to, and amendment of, the Constitution of the United States of America … pursuant to the fifth Article of the original Constitution."

The House's proposed seventeen amendments (attested in print the House Clerk John Beckley and Senate Secretary Samuel A. Otis) were "printed for the consideration of the Senate," which, through debate and reconciliation, combination and elimination, produced a roster of twelve projected amendments, which was approved by the two houses of congress on 24 and 26 September 1789, a month after the present printing (see following lot).

Of the seventeen proposed House amendments, the third and fourth combined into one (the present First Amendment), the fifth through tenth, the thirteenth, fifteenth, and seventeenth became, with minor emendation, the Bill of Rights as adopted. (Of the twelve-amendment Senate version, the ten amendments that became the Bill of Rights were the third through twelfth.) Oddly, the second amendment proposed in both the seventeen- and twelve-amendment resolutions "mandated that any pay raises for Congress take effect only after an intervening election. This would prevent legislators from increasing their own salaries immediately. Americans apparently did not consider this issue very important at the time, and the states failed to ratify the amendment. Incredibly, in 1992, after sitting on the books for over two centuries, the proposal finally achieved ratification by more than three-fourths of the (now fifty) states, and it became part of the Constitution as the Twenty-Seventh Amendment" (CCC, p. 86).

Very rare: Thomas Greenleaf's accounts in the records of the Secretary State indicate that only one hundred copies of this House resolution were printed for the use of congress. No other copy can be traced in the auction records, and the North American Imprints Project locates copies only at the Library of Congress and National Archives.

REFERENCE

Colonists, Citizens, Constitutions 14; ESTC W4280; Evans 22201; see Charlene Bangs Bickford & Helen E. Veit, eds., Documentary History of the First Federal Congress of the United States of America, March 4, 1789-March 3, 1791 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986) 4:1–48, for a chronology of the evolution of the Bill of Rights up to the creation of the 28 September 1789 official copies; cf. Neil H. Cogan, ed., The Complete Bill of Rights: The Drafts, Debates, Sources, and Origins (Oxford University Press, 1997