Arts of the Islamic World & India including Fine Rugs and Carpets

Arts of the Islamic World & India including Fine Rugs and Carpets

The Property of a European Collector

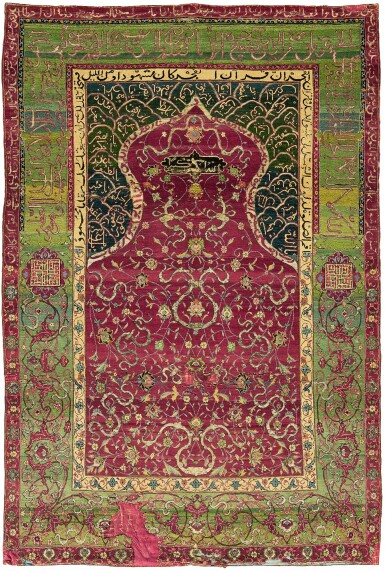

A Safavid Niche Rug, Central Persia, mid-16th century

Auction Closed

March 31, 12:40 PM GMT

Estimate

300,000 - 500,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

mid-16th century

mounted on cloth, the mount approximately 168 by 114cm., the rug approximately 161 by 108cm.

Inscriptions

In the red outer border, in nasta’liq:

Qur’an, chapter II (al-Baqarah), verses 258-259.

In the wide green band, in thulth:

Qur’an, chapter II (al-Baqarah), verse 255.

In the narrow yellow band, in nasta’liq:

Qur’an, chapter XVII (al-Isra’), verses 78-79.

In the narrow band around the arch, in nasta’liq:

Qur’an, chapter XIV (Ibrahim), verses 40-41.

In the spandrel, in thulth:

Invocations to God, calling Him by 36 of His attributes.

In the cartouche in the arch, in fine thulth:

‘God is Most Great, Most High’

In the two square cartouches, in angular Kufic, repeat of:

‘ Success is [from] God, ‘Ali is the Friend of God’

The name ‘Ali is given once in red in the centre (instead of four times), and allah four times in blue (instead of eight times).

This rug belongs to the corpus of Safavid Persian niche rugs often referred to as the 'Salting' or 'Topkapi' group of rugs. Named for a carpet bequeathed to the Victoria and Albert Museum by George Salting upon his death in 1909, and for the group of niche rugs in the Topkapi Saray, the attribution and dating of this group of rugs was called into question in the mid-20th century, with Kurt Erdmann proposing they were copies of Safavid work manufactured in late 19th century Turkey. Revered by early scholars such as A. U. Pope, F.R. Martin, F. Sarre, E. Kühnel, W. von Bode and G. Migeon, they were considered superb examples of Safavid weaving. When these rugs appeared on the market they were purchased by renowned collectors such as Charles Yerkes, Dikran Kelekian, Albert Goupil, Stefano Bardini and E. Paravicini, with several of them now in institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Carpet Museum in Tehran, and the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore. The subject of a special session of the International Conference on Oriental Carpets in Philadelphia in 1996 the group was reviewed in light of more recent scholarship including historical and technical considerations, and C14 dating of several of the pieces, and these resulting papers were published in 1999 (Eiland, M.L., Jr. and Robert Pinner, eds., Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies, vol. V, part 2: The Salting Carpets, ICOC, 1999). Scholars now accept that these rugs were produced during the Safavid period with more recent discussions of the group including Jon Thompson, Milestones in the History of Carpets, Milan, 2006, pp. 220-223; "Auction Price Guide," Hali, issue 144, p. 115 and Sheila R. Canby, Shah 'Abbas; the Remaking of Iran, London, 2009, pp. 80-81.

Michael Franses studied and documented the 89 then known niche rugs of Persian design that were considered part of the group, see Eiland and Pinner, op.cit., pp. 42-67. This example, unpublished prior to 1999 and never previously published in colour, is Catalogue no.11 in Franses’ listing (p. 82, left hand column), the so-called Athens Niche rug, it is a probable pair to the ‘Boccara Niche Rug’, last documented with Babazadeh, Zurich in 1979 and present whereabouts unknown These rugs all feature a Persian design and, as in the example here, the majority of them (70) include calligraphic inscriptions, some clearly Shi’ite (which is the case with the present example), with 41 examples having weft-faced metal thread brocading, ibid, p. 53; the fabrication of the metal thread is typical of Safavid Persia (see also Eiland, M. L. III, ibid., pp. 25-30). Thirty-five of these prayer rugs remain in the collection of the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul, with approximately 20 now in Western museums and collections and believed once also to have been in the Topkapi holdings, Franses, ibid, p. 42. These rugs were most probably sold from the Topkapi palace during the depredations of the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78, see Mills, John, ibid,’The Flight from the Seraglio’, p.10.

Mills surmised, op.cit. (and as Jon Thompson said ’I am sure correctly’, Milestones, p. 220), ‘Lastly I would just like to say a few words regarding Istanbul as a source for so many of the pieces now in the West. There is virtually no mention of the rugs in collectors’ hands, such as Goupil, The Rothschilds, Salting, or the like, before late 1878. Why did they appear in such a short space of time? The answer, I believe, can be summed up in a phrase: The Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, in which the western Powers were almost, but not quite, involved. [….] by early 1878 the Russians were at the very gates of Constantinople [....] Accounts of life in the city in The Times and The Illustrated London News show that it was almost in a state of anarchy [...]The Sultan, Abdul Hamid II was living in Yildiz Palace [...] and it seems certain treasures from the Topkapi were sold off in the bazaars for what they would fetch. I believe this is when most of the rugs got into the market. As the anonymous author of the 1903 Burlington Magazine article wrote: “I well remember much hawking of harem treasures in the bazaars of Stamboul during the terrible Winter of the Russo-Turkish war.” This is when Prince Lobanov-Rostovsky bought his rug for 13,000 francs [...] when he was there in 1878 as Russian Ambassador. [...]’

In discussing how so many of these rugs, sixteen of which have specifically Shi’ite dedications, survived in the Topkapi holdings, Michael Franses suggests ‘the vast majority of the 16th century Safavid niche carpets that survive today are the the result of royal gifts preserved in the Ottoman Royal Treasuries. Many were literally rolled up and left quite unused in the storerooms from the time they were given possibly until the siege of Istanbul during the Turco-Russian was three hundred years later, when several were probably sold off.’ (Franses, Michael, ‘Some Wool Pile Persian-Design Niche Rugs’, Eiland and Pinner, op.cit., pp.36 - 136, p. 38). Shi’ism was the official faith of the Safavid dynasty, which had been founded in 1501 by Shah Ismai’l. Ismail's ancestors had been loyal to Ali and to the fourteenth-century Sufi, Sheikh Safi ad-Din, from whom the new dynasty was descended, derived its name, and its view of its moral entitlement to rule, whilst the Ottomans were Sunni. This might account for the rugs not passing into regular use, or it might have been that recognition of their workmanship and rich materials ensured they were stored in the treasury. It does however make the proposal that they were Turkish work very unlikely.

The two most probable ways the rugs would have arrived in the Topkapi are either as booty or as gifts. If booty, the Ottoman occupation of Tabriz in 1534 and again in 1548 could have provided opportunity. If gifts, occasions for these could include the Treaty of Amasya in 1555, or that of Istanbul in 1590, the Safavid embassy to Selim II’s coronation in 1566, or Shahquli’s embassy to Selim II at Edirne in 1567, depicted in the Shahnama of Selim II by Lokman. 1581 fol.53b-54a: ‘Presentation of Gifts by the Safavid Ambassador, Shahquli, to Selim II at Edirne, early in 1567’; Istanbul: Topkapi Sarayi A.3595, (see http://dla.library.upenn.edu/dla/fisher/image.html?id=FISHER_n2002070618&size=2) or the gifts presented to Murad III in 1576, depicted in the Shahinshah Nama, Istanbul University Library, illustrated in Eiland and Pinner, op.cit., p. 41, both of which appear to illustrate rolled carpets. Of course, it is possible that not all the pieces arrived in the Topkapi at the same time, or that they were a mixture of booty and gifts, or the cartoons to weave them could have been distributed across multiple workshops, any of which could go some way to accounting for differences between the rugs. The present example, which Franses categorises as Group B.2a, ibid., p. 43-44 and pp. 81-85 appears to be amongst the earliest of the rugs and is one of ten examples with fields decorated with cloudband scrolls. It is a particularly well proportioned example with its elegantly shaped arch, exquisitely drawn motifs, and carefully articulated conjunctions between the lobed ends of the inscription panel in the main green border, the lobed roundels which enclose the angular kufic al-tawfiq [min] allah ‘ali wali allah, and the scrolling vines of the lower border. The delicate ribbon-like cloudbands are strongly reminiscent of those seen in the large rug previously in Palencia Cathedral, then in the Museum of Art, Cairo (Inv. No. 6337), discussed and illustrated in John Mill’s essay in Eiland and Pinner, op.cit., pp. 8-9, as is the striking colour scheme of crimson and green.

Rugs which have appeared at auction and relate to the 'Topkapi' prayer rugs include the 'Perez' 'Topkapi' prayer rug, sold Christie's London, October 13, 2005, lot 50 (Eiland & Pinner, cat.no.23); the inscribed Safavid prayer rug, Sotheby's London, October 7, 2009, lot 276, previously unknown, probably related to the Ka'aba rug, Mevlana Museum, Konya (cat.no.55, ibid.); the 'Karlsruhe' Safavid niche rug, Sotheby's London, October 6, 2010, lot 394 (cat.no.47, col.pl.7, ibid.); and The New York Niche Rug, Sotheby's New York, June 4, 1988, lot 11 and January 31, 2014, lot 93 (cat.no.51, col.pl.8, ibid.). Respective inks to the three latter examples as follows:

https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2009/arts-of-the-islamic-world-l09723/lot.276.html

https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2010/arts-of-the-islamic-world-l10223/lot.394.html

https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2014/rug-collection-sale-n09104/lot.93.html

A Carbon-14 test was carried out on a sample from this rug in January 2021; the result was a date between 1490 - 1644 with 95.4% probability and 95.4% confidence.

TECHNICAL NOTES:

Pile, asymmetrically knotted, open to the left, woven with arch at top of rug, eight to nine knots per horizontal centimeter, eight knots per vertical centimeter.

Wool pile: Z spun

Wool colours: crimson (probably lac – not tested), pale blush pink, rose pink, madder orange, lemon yellow, sky blue abrashed to very pale blue, powder blue, dark walnut, dark emerald green abrashed to jade green, bright apple green to grass green (10)

Cotton: white (all the white highlights and the white inner guard are piled in cotton)

Metal thread: ivory silk Z ply, S-bound flat silver metal filament, now oxidized

Warps: yellowish ivory silk, partially depressed

Wefts: yellowish ivory silk 3 shoots

Upper end with minute amounts of striped silk plain weave, in madder, walnut and ivory

Lower end with minute amounts of crimson silk plain weave end finish

Side cords: vestiges of crimson wool binding