Art of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas

Art of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas

Property from the Estate of Valerie Franklin, Sold to Benefit the Hood Museum of Art

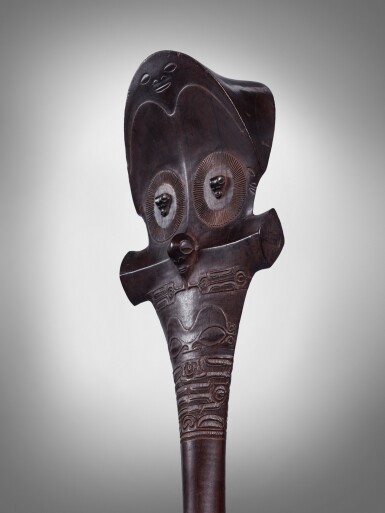

War Club, Marquesas Islands

Lot Closed

May 18, 06:04 PM GMT

Estimate

40,000 - 60,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from the Estate of Valerie Franklin, Sold to Benefit the Hood Museum of Art

War Club, Marquesas Islands

Length: 56 1/4 in (142.9 cm)

Valerie Franklin, Los Angeles, by descent from the above

Carol S. Ivory, the scholar of Marquesan art, notes that “warfare was an integral part of Marquesan life” (Kjellgren and Ivory, Adorning the World: Art of the Marquesas Islands, New York, 2005, p. 85), whether as the result of territorial rivalries or because of the need to obtain redress for perceived slights, insults, or humiliation. Important warriors were, therefore, amongst the most influential and high-ranking members of Marquesan society, and their most prized possession and emblem was an ‘u‘u. These large, heavy, and exquisitely decorated clubs were carved from ironwood (Casuarina equisetifolia), known to the Marquesans at toa, which is also the Marquesan word for warrior. Samuel H. Elbert notes that "In Marquesan, intangibles are named for visible things [...] Heroic or manly is iron-wood tree (toa), the toughness and strength of which is proverbial." (Elbert, "Chants and Love Songs of the Marquesas Islands, French Oceania", The Journal of the Polynesian Society, Vol. 50, No. 198, 1941, p. 55).

The great distinguishing feature of all ‘u‘u is the janiform head of the club, which is covered in an array of small heads and faces. These are arranged in such a way that together they form a larger face, a sort of visual "pun", in which the eyes and nose are made of small heads. The array of faces on an ‘u‘u held many layers of meaning. First, we should note that the Marquesans held the head to be the most sacred, or tapu part of the body, as the site of a person’s mana, or spiritual power. Also important is that the Marquesans call both the face and the eyes mata, and that this word has great genealogical significance. Ivory notes that “the recitation of an individual’s genealogy was referred to as matatetau, literally ‘to count or recite (tetau) faces/eyes (mata)’ […and] the term mata ‘enana (face/eye people) refers to one’s relatives, ancestors, or allies […] Thus, the symbolic relationship between images of the face or eye and an individual’s ancestry – and, by extension, the sacred power of the ancestors – begins to become apparent” (Kjellgren and Ivory, ibid., p. 33).

The purpose of the ‘u‘u was to render its owner powerful and invulnerable. As a heavy war club it served this purpose in a very literal sense, but as Ivory’s remarks make clear, it unquestionably had great spiritual power too, as a vessel for ancestral mana. The anthropologist Alfred Gell has made a similar suggestion, noting his belief that in the Marquesas Islands all imagery, whether carved or tattooed, is a vehicle for etua (gods, or deified ancestors) “in a tutelary […] guardian mode” (Gell, cited in Hooper, Pacific Encounters: Art and Divinity in Polynesia, 1760-1860, London, 2006, p. 163). The imagery on the club does not “represent” etua, figuratively or abstractly, but rather it constitutes their protective presence within the object itself. Considering these theories, and the traditional belief in the Marquesas Islands that it was sacrilege to approach a chief or warrior from behind, it seems probable that the multiplicity of faces on an ‘u‘u were intended in part to represent the all-seeing and watchful character of the ancestors. Tiny yet watchful, they ensure that a vigilant ancestor faces out in all four cardinal directions.