True Connoisseurship: The Collection of Ezra & Cecile Zilkha

True Connoisseurship: The Collection of Ezra & Cecile Zilkha

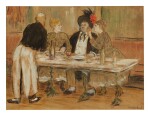

JEAN-FRANÇOIS RAFFAËLLI

LE PROVINCIAL À PARIS

Auction Closed

November 20, 10:09 PM GMT

Estimate

80,000 - 120,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

JEAN-FRANÇOIS RAFFAËLLI

LE PROVINCIAL À PARIS

signed lower right: J.F. RAFFAËLLI.

oil, charcoal and watercolor on board laid down on panel

panel: 20 by 26 in.; 50.8 by 66 cm

We would like to thank Brame & Lorenceau for confirming the authenticity of this work which will be included in its digital catalogue critique on the artist now in preparation.

M. Imberti

Colonel C. Michael Paul, Palm Beach

By whom sold ("Property from the Estate of Colonel C. Michael Paul, Palm Beach, Florida"), New York, Sotheby’s, 13 February 1985, lot 109

There acquired

Colonel C. Michael Paul, Palm Beach

By whom sold ("Property from the Estate of Colonel C. Michael Paul, Palm Beach, Florida"), New York, Sotheby’s, 13 February 1985, lot 109

There acquired

A. Alexandre, Jean-François Raffaëlli, Paris, 1909, p. 95, reproduced

Paris, Galerie Simonson, Oeuvres par J.F. Raffaëlli, 5 - 20 November 1929, no. 58

Jean-François Raffaëlli was a unique voice in the Paris art establishment in the late nineteenth century. During his lifetime he was critically acclaimed at the Salon where, like Edouard Manet, he tenaciously sought inclusion, but he also participated in the landmark Impressionist exhibitions of 1880 and 1881. Raffaëlli trained in the studio of Jean-Léon Gérôme but also befriended Edgar Degas, who would become an ardent supporter. Recognized as an exquisite draftsman, he invented a novel implement called a bâtonnet Raffaëlli, an oil stick that yielded a medium between oil and pastel. Yet in spite of all of these accomplishments, Raffaëlli’s name has all but disappeared from the art historical canon.

After an early start depicting fête galante subjects reminiscent of the work of Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, Raffaëlli’s career took a turn in 1877 when his submission to the Salon, The Family of Jean-le-Boiteux, Peasants of Plougasnou-Finistère,was admired for its creativity and originality by the well-known critic Edmond Duranty. It was at this auspicious moment that Raffaëlli met Edgar Degas. Unlike most of the “pure” Impressionists of the 1870s, Degas and Raffaëlli shared a predilection for drawing, which may well have been the basis for the sympathetic relationship between the two artists.

In 1879, exhausted and verging on nervous collapse, Raffaëlli left Paris and settled in the suburb of Asnières. With its incessantly spewing smokestacks, this desolate region provided the backdrop for Raffaëlli’s paintings from this period, its inhabitants his new protagonists.There, among the faces and expressions of its inhabitants — retired workmen, rag pickers, beggars, garlic sellers and chimney sweepers — Raffaëlli found his inspiration and the vehicle to reveal what he defined as man’s distinctive trait: character, which, according to the artist’s treaty on caractérisme was “the physiological and psychological constitution of man…character is man’s distinctive trait” (J.F. Raffaëlli, “Etude des mouvements de l’art moderne et du beau caractériste”, Catalogue illustré des oeuvres de J.F. Raffaëlli exposés 28 bis, Avenue de l’Opéra, Paris, 1884, p.66-67). Commenting to Edmond de Goncourt, Raffaëlli confessed that, despite traveling throughout Europe and Africa, his search for the essence of the human personality led him to his own backyard in Asnières (Edmond and Jules de Goncourt,”16 February 1888,” Journal: memoires de la vie littéraire, ed. Robert Ricatte, Paris, 1956, vol. III, pp. 755-6).

The artist’s exploration of caractérisme was additionally influenced by the writings of the Goncourts, Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac and especially Émile Zola, and his connection to the literary world of Paris resulted in Les Types de Paris, an extensively illustrated album of stories by the most prominent Realist and Naturalist writers in Paris, published in 1889. Albert Wolfe, the art critic for Le Figaro, commented in his introduction for Les Types de Paris that Raffaëlli was indeed a modern painter with new ideas. But of even greater significance, he was human (Albert Wolff, “Jean François Raffaëlli,” Les Types de Paris, Paris, 1889, p. 6).

In the present work, and the two following, Raffaëlli depicts soldiers, prostitutes, and modest men whose hard work is balanced by the pleasure and satisfaction afforded by a few moments in a bar or restaurant. The tonal shades of the Le provincial à Paris and La forte chanteuse reinforce the smoky interiors of the artist’s local haunts, and the hazy moral decisions made within them. Filled with moments of humor, defiance and resilience, these works allow Raffaëlli to say much about his subjects by saying little, and thereby revealing the subject’scharacter; the artist has turned the intangible into the tangible.

After an early start depicting fête galante subjects reminiscent of the work of Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, Raffaëlli’s career took a turn in 1877 when his submission to the Salon, The Family of Jean-le-Boiteux, Peasants of Plougasnou-Finistère,was admired for its creativity and originality by the well-known critic Edmond Duranty. It was at this auspicious moment that Raffaëlli met Edgar Degas. Unlike most of the “pure” Impressionists of the 1870s, Degas and Raffaëlli shared a predilection for drawing, which may well have been the basis for the sympathetic relationship between the two artists.

In 1879, exhausted and verging on nervous collapse, Raffaëlli left Paris and settled in the suburb of Asnières. With its incessantly spewing smokestacks, this desolate region provided the backdrop for Raffaëlli’s paintings from this period, its inhabitants his new protagonists.There, among the faces and expressions of its inhabitants — retired workmen, rag pickers, beggars, garlic sellers and chimney sweepers — Raffaëlli found his inspiration and the vehicle to reveal what he defined as man’s distinctive trait: character, which, according to the artist’s treaty on caractérisme was “the physiological and psychological constitution of man…character is man’s distinctive trait” (J.F. Raffaëlli, “Etude des mouvements de l’art moderne et du beau caractériste”, Catalogue illustré des oeuvres de J.F. Raffaëlli exposés 28 bis, Avenue de l’Opéra, Paris, 1884, p.66-67). Commenting to Edmond de Goncourt, Raffaëlli confessed that, despite traveling throughout Europe and Africa, his search for the essence of the human personality led him to his own backyard in Asnières (Edmond and Jules de Goncourt,”16 February 1888,” Journal: memoires de la vie littéraire, ed. Robert Ricatte, Paris, 1956, vol. III, pp. 755-6).

The artist’s exploration of caractérisme was additionally influenced by the writings of the Goncourts, Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac and especially Émile Zola, and his connection to the literary world of Paris resulted in Les Types de Paris, an extensively illustrated album of stories by the most prominent Realist and Naturalist writers in Paris, published in 1889. Albert Wolfe, the art critic for Le Figaro, commented in his introduction for Les Types de Paris that Raffaëlli was indeed a modern painter with new ideas. But of even greater significance, he was human (Albert Wolff, “Jean François Raffaëlli,” Les Types de Paris, Paris, 1889, p. 6).

In the present work, and the two following, Raffaëlli depicts soldiers, prostitutes, and modest men whose hard work is balanced by the pleasure and satisfaction afforded by a few moments in a bar or restaurant. The tonal shades of the Le provincial à Paris and La forte chanteuse reinforce the smoky interiors of the artist’s local haunts, and the hazy moral decisions made within them. Filled with moments of humor, defiance and resilience, these works allow Raffaëlli to say much about his subjects by saying little, and thereby revealing the subject’scharacter; the artist has turned the intangible into the tangible.