Music, Continental Books and Medieval Manuscripts

Music, Continental Books and Medieval Manuscripts

J. Brahms. The correspondence with Ernst Rudorff, 16 letters with replies, and an autograph music manuscript 1865-1887

This lot has been withdrawn

Lot Details

Description

BRAHMS, JOHANNES

The correspondence with the conductor Ernst Rudorff, comprising sixteen autograph letters and cards signed ("Johs Brahms and "JBrahms"), an autograph music manuscript, and sixteen autograph letters by Rudorff, 1865 to 1887

BRAHMS’S LETTERS, an apparently intact series, chiefly concerning his work with Rudorff on the complete editions of Mozart, Schumann and Chopin, discussing problematic passages in Mozart’s Flute Concerto in D K.314 (INCLUDING THE AUTOGRAPH MANUSCRIPT OF HIS SOLUTION) and Chopin’s Ballade op.38 (with 3 musical quotations), and the publication of the original versions of Schumann’s early piano works; Brahms also gives Rudorff detailed instructions for the premiere of his orchestration of nine Liebeslieder-Walzer, asks him to include an aria by Handel with the premiere of the “Triumphlied” op.55, discusses his interest in collecting composers’ autograph manuscripts (especially by Schubert), forbids the use of his draft of the Sextet in G op.36 (which Rudorff had acquired from Clara Schumann), forwards Gustav Nottebohm’s enquiry about Beethoven’s sketchbooks (Nottebohm’s letter is included), gives his frank assessment of Rudorff’s Piano Fantasy op.14, and offers condolences on the death of his father and mother

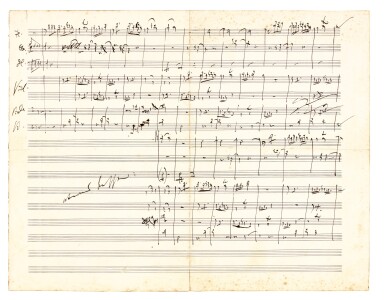

the music manuscript one oblong folio leaf, (one page by Brahms and one by Rudorff), c.26.5 x 34 cm, 16-stave paper; Brahms’s letters 36 pages, mainly large 8vo (up to c.22 x 14cm), 2 on postcards with autograph address panels and 2 on visiting cards, 11 autograph envelopes, 3 letters with red printed monograms, all numbered, annotated and dated by Rudorff in pencil, mainly Vienna, 18 January 1865 to October 1887, slight dust-marking and small tears to edges of the first letter

ERNST RUDORFF’S LETTERS, apparently lacking two items, sending Brahms extensive and detailed queries about Chopin’s Ballade op.38, the B major Nocturne op.9 no.3 and Mozart’s Flute Concerto in D, enclosing a draft of his solution (which Brahms has rewritten on the verso), answering Brahms’s queries about Mozart’s 12-part canon “V’amo di core”, discussing whether Schumann’s Davidsbündertänze and other early works are best served by “double editions”, conceding that printing the earlier readings in small notes is unsatisfactory, sending him a manuscript copy of his Fantasy for piano (op.14) and asking permission to dedicate it to him, asking him to coach the choir in Cologne (initially with the German Requiem op.45), giving detailed reports on his premiere of Brahms’s orchestral version of the Liebeslieder-Walzer, and on Joachim’s performance of the First Symphony in Berlin, sending news of Clara Schumann, Ferdinand Hiller, Hermann Levi, Amalie Joachim and others, regularly praising Brahms’s songs (including the “Magelone-Lieder” op.33), giving a fulsome appreciation of the Third Symphony in 1884 and promising to return Brahms’s score of the Liebeslieder-Walzer, 16 letters, 43 pages, 8vo, with musical examples, Cologne and Berlin (Lichterfelde), 8 November 1865 to 18 December 1886; together with 6 documents and letters about the return of Rudorff's letters from the Brahms Estate, signed by Dr Richard Fellinger and the lawyer Dr Joseph Rietzes, Vienna, 7 April 1901-6 August 1903

THIS IS THE ONLY COMPLETE SERIES BY BRAHMS TO HAVE BEEN OFFERED FOR SALE AT AUCTION. The presence of nearly all Rudorff’s side of the correspondence makes this collection especially valuable, as well as helpful for understanding Brahms’s letters, characteristically telegraphic replies to Rudorff's entreaties, queries or reports. A fair number of Brahms’s correspondence cards written to his publisher Fritz Simrock have been offered for sale, individually or in groups, but never a complete series such as this, which is entirely new to the market.

These letters display the wide range of Brahms’s interests and activities in music. He gives practical advice on performing his own works (see letter no.4 below) and expresses his concern to keep control of it (letter no.1). But he also reveals himself as a scholar, connoisseur and collector of music, both from earlier periods, and also, albeit anonymously, as editor and advisor on the Complete Works of his great friend and mentor Robert Schumann (letter no.12). As a scholar, he was very close to Gustav Nottebohm, the pioneer of Beethoven sketch studies, and here seeks to further his research into manuscripts in Berlin (letter no. 8). As an editor, Brahms is punctilious but practical, intent on creating editions of Mozart and Chopin that are true to the composers’ intentions, seeking out autograph manuscripts but not necessarily following the available sources where they were unsatisfactory (letter no.13). He also expresses some misgivings about filling his study with bulky volumes of already published composers, suggesting that he would prefer to have reliable manuscript copies, encompassing a wider repertory, accessible in libraries (letter no.11). Finally, Brahms was one of the greatest nineteenth-century collectors of musical autographs (among his treasures were over sixty Beethoven sketchleaves and Mozart’s G-minor Symphony, K.550), and here he reveals his special interest in Schubert (letter no.5) and in the fate of Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito.

Ernst Rudorff (1840-1916) was a leading German musician and, like Brahms, a close friend of Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim. A pianist, composer and conductor, he was for forty years head of piano studies at the "Hochschule für Musik" in Berlin, where Joachim was director. He was also heavily involved in Breitkopf & Härtel’s Complete Editions of Mozart, Chopin and Schumann, monuments to nineteenth-century musical scholarship. It is a mark of Brahms’s regard for Rudorff that he appears to have kept almost all the letters that he received from him.

Brahms's autograph letters and cards comprise:

1) Vienna, 18 January 1865: Brahms expresses regret that he cannot allow Rudorff to use a copy of the Sextet in G op.36 that he received from Clara Schumann, since it is merely an error-strewn draft, which he feels ashamed to have sent to her in the first place, asking his indulgence for the negative answer which is prompted by his premonitions of the most ghastly rehearsal resulting from such a terrible manuscript (“...Verzeihen Sie das Nein und sei[e]n Sie versichert daß ich es nur sage weil ich schon in Gedanken die unerquicklichste Probe höre wenn nach jener liederlichen Schreiberei musiziert wird…”), 2 pages, large 8vo, [Altmann (I) p.145]

Brahms was still working on the Sextet in G at the time of this letter, completing it in May 1865, whilst staying with Clara Schumann at Baden Baden. Clara describes a play-through of "ein ganz reizendes Sextett" at Karlsruhe in a letter to Rudorff of 10 September 1865 (see also Clara's letters to Rudorff: lot 35), but the work was not performed publicly until 11 October 1866. The Sextet was published by Simrock as op.36 in April 1866.

2) Vienna, [c.25] January 1869: Brahms thanks Rudorff for the dedication of his Piano Fantasy op. 14, telling him nevertheless that he finds it rhythmically rather brusque, admitting that he cannot resist trying to force the first movement into a more regular metre, without losing its essentially dreamy character (“...Mir scheint Sie behandeln den Rythmus etwas rücksichtlos oder sorglos. Ich muß bekennen daß ich dem Versuch nicht widerstehen kann gleich das erste Stück Ihrer neuen Fantasie--ohne seinen sanft träumerischen Character zu vergessen--in etwas regelmäßigere Taktzahl zu bringen…”), 4 pages, 8vo, [Altmann (IV) p.149]

3) Vienna, [9 February 1869]: Brahms assures Rudorff that he has sent back his Fantasy op.14, remarking that whilst he would relish taking over directing the Choir at Cologne (which Rudorff has suggested), and working with Ferdinand Hiller, both the city itself and being compelled to teach there would deter him (“...Mich könnte der Umgang mit Hiller und die Beschäftigung mit dem Chor nach K[öln] locken--die Stadt selbst und das Stundengeben schrecken mich ab…”), 3 pages, 12mo, with a lengthy pencil annotation by Rudorff, emphasizing Brahms’s good relations with Hiller, discounting the false report by Hugo Riemann about their falling out at the Beethoven festivities in Vienna in 1870, and a separate note about it by his daughter [Altmann (VI) p.152]

4) Vienna, January 1870: about the orchestral version of the Liebeslieder-Walzer op.52; Brahms permits Rudorff to premiere his arrangement, having declined his earlier request made through Clara Schumann, explaining that although nothing is ready to send to the copyist, he is nevertheless letting him have drafts of nine numbers, leaving their realization to his discretion (“kann ich sie nicht einmal ansehen”), although expressing doubts that Rudorff will be able to get his rough versions copied and performed without problems; he emphasizes that the tempo is that of a Ländler, that is to say the livelier numbers should be Andante (“Mässig”), the more sentimental ones not too slow, and that only solo voices are to be used (“...Ich brauche nicht zu sagen daß des Tempo eigentlich das des Ländlers ist: Mäßig. Sonderlich die Lebhaftern mäßig (C moll, A moll), die Sentimentalern bitte nicht schleppend (Hopfenranke)...Solo--nicht Chor, wie ich meine…”), 4 pages, 8vo,[Altmann (VIII) p.155; Avins no.247]

The Liebeslieder-Walzer are a collection of love songs in Ländler style for solo voices and piano duet, possibly inspired by Brahms’s love for Clara Schumann. The composer’s arrangement for orchestra was not published until 1938. Brahms here clarifies the single tempo marking in the score, found above the first number (“Im Ländlertempo”). He refers specifically to ‘Die grüne Hopfenranke’ op.52 no.5 (in A minor) and ‘Nein, es ist nicht auszukommen’ op.52 no.11 (in C minor). Also included was one as yet unpublished number from the Neue Liebeslieder, ‘Nagen am Herzen’ op.65 no.9.

5) Vienna, 31 March 1870: about collecting composers' autograph manuscripts; Brahms tells Rudorff, that he can send him back the copies of the Liebeslieder-Walzer, whilst keeping the small-format autograph score (as Rudorff had, with a heavy heart, offered to return his "kleines hübsches Manuscript"), admitting that he has himself also obtained autographs serendipitously, that he has been looking around for some Schubert for years, whilst finding only first editions of Die schöne Müllerin, pointing out that the autograph of Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito is currently being offered for sale in Vienna and wondering if the Berlin Royal Library should not acquire it, perhaps as a gift from a wealthy Prussian looking for a title or a Knighthood (“..Ebenso muß ich lachen daß mir bei der Gelegenheit andre Manuscripte einfallen. Ich wollte aber doch erzählen daß ich seit Jahren nach “Schubert” für Sie umschaue ohne daß es mir gelingen will etwas zu erwerben...Jetzt jedoch ist hier die Handschrift vom Titus zu verkaufen. Thäte denn die Berl[iner]-Bibl[iothek] keinen Versuch darum? Oder ein Titel- oder Ordensbedürftiger Preusse?--um sie der Bibliothek zu schenken...”), 4 pages, 8vo, [Altmann (X) p.159]

6) Bremen, 3 April 1871: about Handel; Brahms thanks Rudorff for conducting his concert in Bremen, where the Requiem and, for the first time, part of the Triumphlied op.55 were being performed, urging him to persuade and train the baritone singer Otto Schleper to perform the aria ‘Dignare o Dominum’ from Handel’s Te Deum between the pieces and, if he refuses, to choose something suitable, but not anything from Mendelssohn’s “St Paul” (“...Frau Wilt singt einiges aus “Messias”, und von Schelper wünschen wir das “Dignare Domine” aus Händels Te Deum…Nur wünschen wir nicht daß er als “Paulus” sterbe…”), 2 pages, large 8vo, autograph envelope inscribed by Betty Pistor, redirecting the letter from Berlin to Wienrode bei Blankenburg, [Altmann (XI) p.161]

Brahms probably intended Rudorff to include the baritone aria 'Vouchsafe, O Lord' from the “Dettingen” Te Deum HWV 283, although he refers to the Latin title, whereas Handel’s work is in English (Chrysander’s edition was published in 1865).

7) [Lichtenthal bei Baden, 27 September 1870]: Brahms tells Rudorff that he has only just discovered by chance, among Clara Schumann’s bookshelves, the copy of his edition of Weber’s Euryanthe which he had kindly dedicated to him in 1867 (“...Ich war vermutlich in jenem Sommer nicht in Baden, und Fr. Sch. vergaß mein schönes Eigenthum…”), 2 pages, 8vo, [Altmann (XII), p.163]

8) [Vienna, 20 March 1872]: about Gustav Nottebohm; Brahms commends his friend’s research on Beethoven’s sketchbooks, forwarding his letter requesting details of what manuscripts are to be found at the Royal Library in Berlin, telling him that Nottebohm will follow up with a request for copies of anything that he finds of particular importance (“...Hr. N. wünscht einstweilen natürlich nur zu erfahren ob und was vorhanden ist. Erscheint ihm etwas wichtiger so wird die Bitte folgen ihm von Solchem eine Copiatur besorgen zu wollen…”), 3 pages, 12mo, on Brahms’s red monogrammed stationery, together with the enclosed letter by Nottebohm (2 pages, 8vo, on blue paper), [Altmann (XIII) p.163; Avins no.275]

9) [after 14 February 1873]: Autograph note signed (“JBrahms”) on a card, commiserating with Rudorff and his mother [Betty Pistor] over the death of his father Adolf ("Mit theilnahmsvollstem Gruss, namentlich auch an Ihre verehrte Frau Mutter!"), 1 page, c.5.5 x 9.5cm, autograph envelope annotated and dated by Rudorff in pencil (“Nach dem 14ten Febr.1873 dem Todestage meines Vaters”), not in Altmann

10) [Vienna 1876]: Printed visiting card inscribed by Brahms: "mit herzlichstem Gruß und Wünsche", autograph envelope annotated and dated by Rudorff (“Glückwunsch...1876”), not in Altmann

11) [Vienna, 1 November 1877]--ABOUT CHOPIN, CONTAINING THREE MUSICAL QUOTATIONS, from the Ballade no.2 op.38; an important letter about editing music, in which Brahms answers Rudorff’s detailed enquiries in his letter of 21 October (also present), regarding three doubtful passages, namely the end of the opening ‘Andantino’ in F, a bass figure in the subsequent ‘Presto’ in A minor, and some consecutive fifths in the ‘Tempo Primo’ that follows, deciding that the readings in the first edition should be retained, pointing out parallels elsewhere, and enthusiastically endorsing the fifths and quoting them back to Rudorff (“...Für die 3 Quinten aber bin ich am entscheidendsten!...”); with regard to scholarly editions in general, Brahms recommends a flexible approach since a consensus on trifling details is hard to achieve, urging against changing Chopin’s accidentals (it would only be a short step to correcting his sentences!), and expresses his reservations about the ongoing complete sets of Handel and Mozart, preferring to see manuscript copies of pieces available in big libraries rather than crowding out his study with imposing volumes, when other interesting composers are ignored (“...Festere Normen würden wohl den einzelnen schon bald genieren, mehrere können wohl nur ganz beiläufig über manches einig sein. Sehr wünschte ich, Bargiel wäre mit uns eins daß wir nicht versuchen Chopins Orthographie verbessern zu wollen! Es wäre nur ein kleiner Schritt auch seinen Satz anzugreifen…”), 4 pages, 8vo, [Altmann (XV) p.167; Avins no.360]

Brahms edited six volumes for Breitkopf & Härtel’s complete edition of Chopin’s works (1878), including the Mazurkas, Nocturnes, Sonatas, the Barcarolle and chamber music. He had suggested that Rudorff and Bargiel were involved, but was evidently in control of the whole project himself. He shows here a deep knowledge of Chopin’s music, despite rarely including any in his recitals. Brahms’s comments about the consecutive fifths in the Ballade are characteristic. From the 1860s, he began compiling a manuscript of “forbidden” fifths and octaves, clearly relishing examples that he considered effective (“Octaven u. Quinten u. A”; see M. Macdonald, Brahms (1993) p.149). Styra Avins has kindly pointed out that Brahms once confided to Rudorff that, whilst he had played Chopin in his youth, he never felt at home with his music.

12) [Vienna, 13 March 1879]: ABOUT SCHUMANN; Brahms discusses the publication of the original versions of some of Schumann’s early piano works for the Complete Edition, somewhat delicately broaching the idea of issuing Impromptus op.5, the Davidsbündlertänze op.6 and the Symphonic Studies op. 13, each with both versions complete and not relegating the originals to an appendix, as had happened with a recent edition of op.5, nor printing several versions weighed down with a mass of analysis, as happened with op.6; he finds the latter ruins the pleasure in literary works, all the more so with music (“...Nicht wie z.B. bei op.5 jetzt geschehen: in einem Anhang die ältere Lesart und nicht wie bei op.6 die verschiedenen [deleted: “Lesarten”] Bearbeitungen in Noten und Anmerkungen geben. Letzteres verdirbt mir auch bei Schriftstellern den Genuß wie viel mehr bei Musik..”). 3 pages, 8vo, [Altmann (XVII) p.171]

Brahms found that publishing the original versions of Robert Schumann’s works, which he usually preferred, required considerable delicacy; it strained his relationship with Clara Schumann when, in 1891, he published the Fourth Symphony in its original form. Hofmeister of Leipzig had published Schumann’s 1850 revision of the Impromptus op.5 including the original version as an appendix, whilst Schuberth had published scholarly editions of the Davidsbündlertänze op. 6 and the Symphonic Studies with copious notes and analyses by a certain "DAS" (either Adolf Schubring or Friedrich Wieck). During 1885-1887, all three works appeared in the Complete Edition with the original versions first, but without commentary or mention of Brahms’s contribution.

13) [Vienna, c.22 December 1880]--AN AUTOGRAPH MUSIC MANUSCRIPT AND COVERING LETTER: A) in his working manuscript Brahms sketches a solution for a problematic passage in Mozart’s Flute Concerto K.314 (285d), about which Rudorff has sought his help; Brahms writes his musical solution on the verso of the proposed draft that Rudoff sent him on 18 December, consisting of two versions, a first draft and a revised version written out below the first, marked “etwas besser”, comprising twenty-four bars music in all, rather hastily notated in full score on two systems of seven staves each, with deletions, alterations and revisions-- B) in his letter Brahms describes the manuscript sources in Vienna and urges Rudorff to maintain Mozart's imitative texture at all costs, even if it means changing the text even more boldly than he has outlined in his manuscript (“...Meines Erachtens bringen Sie besser die geänderte Stelle im Text und zwar dreist geändert. Von der Nachahmung, meine ich, dürfen Sie nicht abgehen, und wenn Sie auch viel mehr (d.h. besser) ändern, als ich es auf Ihrem Blatt vorschlage…”), the manuscript (A): 2 pages in all, large oblong 4to (c.26.5 x 34 cm): one page by Rudorff, the verso by Brahms, on 16-stave paper--the letter (B): 1 page, 8vo, [Altmann (XX), p.176]

This is a remarkable manuscript showing Brahms reconstructing a passage by Mozart. In preparing Mozart’s Concerto in D major K.314 for the Complete Edition, Rudorff had found that his sources were evidently corrupt, being based on inaccurate instrumental parts in the Archive of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna. (There is no autograph for K.314, which Mozart originally composed in C major, as an oboe concerto). The passage in question is found at bars 152-164 of the last movement--Rudorff could not produce an imitative passage from the parts that reflected an analogous passage near the beginning (bars 36ff), and he asked Brahms if he could come up with a version that worked. However, Rudorff declined to follow Brahms’s advice in his 1881 edition, thereby losing the imitation between the flute solo and the first violins. Brahms’s counterpoint later proved to be rather close to Mozart’s, authentic parts for which were only discovered in 1920 (cf Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, V/14/3 (1981), p.82). Brahms’s general approach to editing, as expressed in this letter, was to go for the spirit of Mozart’s musical conception, rather than to follow the manuscripts slavishly, but this was evidently too much for Rudorff, even though he knew his sources were corrupt.

14) [Vienna, 17 May 1881]: Brahms now asks Rudorff to answer a Mozart problem of his own, about the Canon “V’amo di core” K.348 (382g), which he is quite certain Mozart composed for four four-part choirs, not three, and that there should therefore be an additional C in the bass in bar 6 (which he notates); he asks Rudorff to check the autograph manuscript which should be in the Royal Library in Berlin, to see whether it is clear on this matter or leaves some room for doubt (“...Es scheint mir gar so selbstverständlich daß der Canon für 4 stimm[ige] Chöre ist und der 4te Chor im 5ten Takt natürlich anfängt. Namentlich das zu Anfang des 6ten Taktes fehlende [C] ist gar so unwidersprechlich...”), 2 pages, 8vo, autograph envelope, [Altmann (XXI) p.177]

Brahms questions the text found in Gustav Nottebohm’s edition of “V’amo di core” (1784/85) in the Mozart Complete Edition (1877). In fact, although it would have been technically possible for Mozart to have added a fourth choir in canon with the others, there is no sign in his autograph of any attempt to do so, nor of the words needed for it, as Rudorff explains in his reply of 21 May (Altmann, p.178): see also Neue Mozart-Ausgabe III/10/5 (1974), page 24, & ‘Critical Report’ (2007), p.12, where the piece is described as a quadruple canon in twelve parts, the only example in Mozart’s oeuvre. It is not inconceivable, however, that a fourth entry, perhaps even with a continuo accompaniment - by analogy with the rather similar canon K.73x no.1, might have been written out on a separate, now lost, leaf (on K.73x no.1, see John Arthur, 'The watermark catalogue of the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe: some addenda and corrigenda', in The Musical Times, vol.159 no.1945 (Winter 2018), pp.87-89).

15) [Vienna, 7 January 1884]: Brahms thanks Rudorff for his enthusiastic appreciation of the Third Symphony op.90 in his letter of 5 January (Altmann, p.178; Avins no.431), the first exchange between them since breaking off relations over Joachim's divorce; Brahms echoes Rudorff’s ploy of asking him to "read between the lines" (“...Ich aber versuche erst recht nicht ausführlicher zu sein! Lesen Sie nur hübsch zwischen den Zeilen und über die Karte hinaus...”), 1 page, oblong 8vo, on a “Correspondenz-Karte”, autograph address to verso, postmarked, dated by Rudorff “7. Januar 1884, Wien”, [Altmann (XXIV) p.180; Avins no.432]

In 1880-1881, during the acrimonious divorce proceedings between Joachim and his wife Amalie, Brahms had taken Amalie’s side against his old friend and collaborator, whilst Rudorff, who taught at Joachim’s conservatory in Berlin, remained loyal and broke off relations with the composer. Rudorff's letter represents an attempt at reconciliation as well as a musical tribute. Apart from this brief exchange and a later letter from Rudorff (18 December 1886), praising the Triumphlied op.55 and saying that he had thought of asking Brahms to conduct it in Berlin (which Brahms apparently did not answer), there remains one final note of condolence:

16) [Vienna, c.26 October 1887]: A printed visiting card inscribed by Brahms, commiserating with Rudorff over the death of his mother Betty Pistor (“[Johannes Brahms] in herzlicher Theilnahme”...), 1 page, c.5.5 x 9.5cm, autograph envelope, postmarked (“Wieden Wien 26/10/87”), annotated by Rudorff (“Oct. 1887 nach dem Tode meiner Mutter”), not in Altmann

LITERATURE:

W. Altmann (editor) Johannes Brahms. Briefwechsel, volume 3 (1908) [...mit Karl Reinthaler, Max Bruch, Hermann Deiters, Friedrich Heimsoeth, Carl Reinecke, Ernst Rudorff, Bernhard und Luise Scholz]; S. Avins, ed., Johannes Brahms: Life and Letters (1999). P. Clive, Brahms and His World: A Biographical Dictionary (2006), pp.377-379

Please note: Condition 11 of the Conditions of Business for Buyers (Online Only) is not applicable to this lot.

To view Shipping Calculator, please click here