Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, Juan Hamilton: Passage

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, Juan Hamilton: Passage

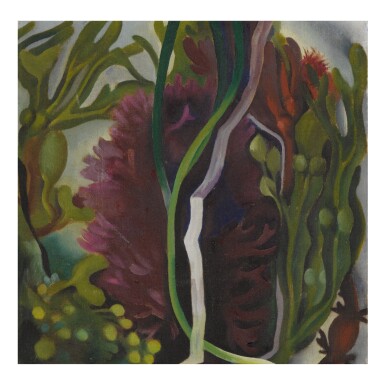

GEORGIA O'KEEFFE | SEAWEED

Auction Closed

March 5, 05:19 PM GMT

Estimate

300,000 - 500,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

GEORGIA O'KEEFFE

1887 - 1986

SEAWEED

signed Georgia O'Keeffe (on the reverse)

oil on canvas

7 by 7 inches

(17.8 by 17.8 cm)

Painted circa 1923.

[with]Alfred Stieglitz, New York

Alma Morganthau Wertheim, New York, 1920s

An American Place, New York, 1946

Ulrich Frank, New Haven, Connecticut

Princeton Gallery of Fine Art, Princeton, New Jersey, 1974

The artist, 1980 (acquired from the above)

Gift to the present owner from the above, 1981

Barbara Buhler Lynes, Georgia O'Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné, vol. I, New Haven, Connecticut, 1999, no. 440, p. 237, illustrated

New York, The Anderson Galleries, Alfred Stieglitz Presents Fifty-One Recent Pictures: Oils, Water-colors, Pastels, Drawings, by Georgia O'Keeffe, American, March 1924, no. 24 (as Sea-Weed), n.p.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s images of botanical forms rank among the most important and celebrated of her body of work. She utilized natural subjects as the basis for her unique visual language from the earliest years of her output, exploring the bucolic landscape of diverse locales like West Texas, Lake George New York, and the coast of Maine, among others, and translating their distinctive characteristics onto canvas. Painted circa 1923, Seaweed demonstrates the wholly unique vision with which O’Keeffe depicted these sources. Resisting a literal transcription of her subject, she instead achieves the exquisitely tenuous balance between abstraction and realism that became central to her singular aesthetic.

While O’Keeffe’s tendency toward abstraction was a conscious one, her vision remained tempered with vestiges of realism as she sought and achieved something more individual. In fact, she saw the two modes of expression as inherently and inextricably linked to one another, explaining, “It is surprising to me to see how many people separate the objective from the abstract. Objective painting is not good painting unless it is good in the abstract sense. A hill or tree cannot make a good painting just because it is a hill or a tree. It is lines and colors put together so that they say something. For me that is the very basis of painting” (Barbara Haskell, Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction, 2009, p. 166).

As such, in the present work O’Keeffe focuses intently on the forms of the seaweed, removes many extraneous details, and isolates them from their larger context, depicting only hints of the aquatic environment beyond. By removing the visual cues that would typically allow for instant recognition of the subject, she compels the viewer to consider the subjects in a new way: for their distinctive shapes, colors and textures, and the formal relationships between them. O’Keeffe manifests a sense of palpable energy through the repetition of geometric and organic shapes and the expressive brushwork she utilizes to render them.

Given her close personal and professional association with Alfred Stieglitz, O’Keeffe certainly explored the modern approach to compositional design he and his contemporaries such as the photographer Paul Strand implemented in their work. Indeed, O’Keeffe and Strand both often portrayed flora in a strikingly similar manner, frequently enlarging their chosen subject to focus on its form at close hand (Fig. 1). Her approach also finds parallels in both aesthetic and intent with the gouaches découpées of Henri Matisse. These works, which the artist created using sheets of paper often embellished with gouache, frequently took botanical designs as subject matter. Matisse explored this new technique near the end of his storied career. Examples such as La Gerbe, a work executed in ceramic that is based on a paper cut-out of the same title (Fig. 2), are considered the summation of Matisse’s tireless exploration between the relationship between color and line. Free of inessential decorative details and any larger narrative context, they liberate the viewer to observe the lyrical patterns of design and form present in the French master’s representational sources.

Yet ultimately O’Keeffe’s interpretation of the world was entirely her own, and she considered her art to be the very expression of herself. “I have things in my head that are not like what anyone has taught me,” she explained, “shapes and ideas so near to me—so natural to my way of being that it has not occurred to me to put them down.” As such, works like Seaweed demonstrate O’Keeffe’s distillation of various influences into her own unique style. “From [Arthur Wesley] Dow and art nouveau O’Keeffe had learned about composition and design, from Picasso and Braque she had received instruction about form and structure, and from Kandinksy and Matisse she had garnered invaluable insights into color. From Stieglitz and other photographers she learned how to read photographs, how to appropriate some of their strategies, and how she could both utilize and undercut the mimetic properties of the medium in order to present 'the real meaning of things'” (Sarah Greenough, Modern Art and America, Washington, D.C., 2000, p. 289).