20th Century Art / Middle East

20th Century Art / Middle East

Property from a Distinguished Private Collection, France

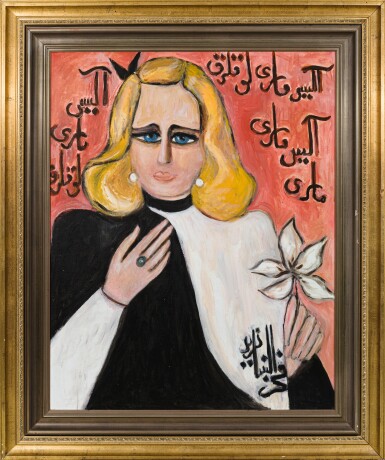

FAHRELNISSA ZEID | MARIE-ALICE

Lot Closed

March 31, 01:46 PM GMT

Estimate

70,000 - 100,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

FAHRELNISSA ZEID

1901 - 1991

Turkish

MARIE-ALICE

signed with the artist's monogram; titled thrice

oil on canvas

100.5 by 80.5 cm.; 39½ by 31⅝ in.

Executed in 1988.

The authenticity of this work has kindly been confirmed by H.R.H. Prince Raad bin Zeid Al-Hussein.

Please note that consumer cancellation rights do not apply to this lot.

To view shipping calculator, please click here

Private Collection, France (gifted by the artist in 1988)

Fahrelnissa Zeid cemented her reputation in the global artworld as an artist of considerable talent, depth and dynamism. While it was perhaps her mesmerizing and all-consuming large kaleidoscopic canvases that catapulted her into the international arena, there has always been something incredibly unique to her portraitures.

Born into a family of intellectuals in 1901, Fahrelnissa Zeid was raised in Buyukada, one of the Princes’ Islands in Istanbul during the reign of the Ottoman Empire. Her uncle Cevat Pasha was the Grand Vizier to Sultan Abdulhamid; Fahrelnissa’s own brother, Cevat Sakir Kabaagacli was widely known as the Fisherman of Halicarnassus in the history of Turkish literature. At the behest of Fahrelnissa’s direct encouragement both of her nieces became artists - her niece Fureya, was the first female ceramicist in Turkey and Fahrelnissa’s sister Aliye Berger, a well-known printmaker. Art seems to have been engrained in the family DNA, with Fahrelnissa’s daughter Sirin Devrim, acting, and her son Nejad Melih Devrim, a member of Nouvelle École de Paris –the entire family shared a passion and talent for creative and artistic endeavours.

Fahrelnissa Zeid moved to London with her husband, Prince Emir, in 1946 after he was appointed as the Iraqi Ambassador to the United Kingdom. The 1940s and 1950s would mark a pivotal new era in Fahrelnissa’s career and artistic output dividing her time between two artistic capitals of London and Paris. Fahrelnissa immersed herself in the art scene in these cities. She was as a result, exposed to a diverse social circle, varying artistic tastes, trends and movements: all of which served to influence and inspire her.

Despite continuing to exhibit in Paris, Fahrelnissa later settled in Amman in the 1970s to join the rest of her family – particularly as her son Prince Raad was now permanently living in Jordan. She continued to paint there while also teaching art to a group of students, ultimately founding the Fahrelnissa Zeid Institute for Fine Arts. Dr. Adila Laïdi-Hanieh, also one of her students, quotes Fahrelnissa’s daughter Shirin as saying this was “the most creative, productive and rewarding period of her life” (Exh. Cat., London, Tate Modern, Fahrelnissa Zeid, 2017, p.131).

Although Fahrelnissa was teaching abstraction to her students at the Institute, she was mainly painting intimate smaller portraits during her Amman period. These included portraits of the artist’s close friends and their children, members of her own family – even her cook and the Turkish Ambassador amongst others. These portraits were mostly done in one or two sittings, many of which were meant as gifts and as private personal mementos for the sitters to remember Fahrelnissa Zeid and capture their friendships. Dr. Adila Laïdi-Hanieh who wrote the most comprehensive biography on the artist in 2017 explains: “The Amman portraits…, reveal a purgation – an exercise in pure painting in her figurative expressionist vein that juxtaposes chromatic simplification with a subject’s character. Focusing her innovative and intellectual energies on her teaching, Fahrelnissa turned to portraiture as a pure exercise of painting ‘for itself’, and for her own sake.” (Exh. Cat., London, Tate Modern, Fahrelnissa Zeid, 2017, p. 132).

Fahrelnissa’s Amman portraits differed from her earlier portraiture of the 1960s to 1972 in the sense that they were pure studies of form and colour and systematically featured a small error in perspective, volume or finishing – to underscore Fahrelnissa’s belief that portraiture ought to be free from reproducing physical appearance and should render an aura of ‘give[ing] life’ (Dr. Adila Laïdi-Hanieh cited in Exh. Cat., London, Tate Modern, Fahrelnissa Zeid, 2017, p. 137). “What Fahrelnissa gave up in textural layering in these portraits, she made up for in the stark chromatic contrasts. She eliminated three-dimensional spaces and linearity for a predominance of colour in the picture plane, achieving a sense of solidity with strong juxtapositions of highly saturated planes of colour in the clothing, hair and background of her subjects. Many of these portraits appear almost like colour studies than portraits.” (Dr. Adila Laïdi-Hanieh, Fahrelnissa Zeid Painter of Inner Worlds, London, 2017, p. 267).

As a result, Fahrelnissa inevitably developed her own unique and characteristic style. Her figures and faces became highly recognizable: ageless sitters with enlarged glaring eyes. The flatness of her portraits were accentuated by thick black outlines – the expressionist technique of cloisonnism (unlike her 1960s portraitures, which displayed more nuance in flesh tone, and more vigour in the paintwork).

Fahrelnissa’s portraits from the 1970s and 1980s in comparison to her portraits from the 1960s, also carry a significance as they were not commissioned portraits. They were visual embodiments of family, friends – of those within her social circle – adding a more personal investment to each. Marie-Alice is one such figure. The photograph in Fig. 2 captures a moment between Fahrelnissa and the sitter – with Marie-Alice wearing the same dress as in the painting. A moment captured on film was transposed into her memory and later expressed through paint: a visual outpouring of human, personal connection. There is a letter of correspondence from Fahrelnissa to Marie-Alice, referencing the painting of the portrait. In this way our access to a written archive of sorts, lends added life and makes clear the personal dimension to the work presented here. Adding further poignancy to this is the notion that Fahrelnissa’s return to portraiture was rooted in the loneliness of widowhood (after 1970). Portraiture made its way back into her oeuvre in the later stages of her life and complete resettlement in Amman.

Fahrelnissa’s works are in the collections of leading museums such as Tate Modern, London, Istanbul Modern, Istanbul and Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha. Fahrelnissa was awarded the Star of Jordan for her contribution to the arts in the country she later called home and she was also made Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres by the French government. A large selection of Fahrelnissa’s works was most recently exhibited at the 12th Sharjah Biennial in 2015 and at the 14th Istanbul Biennial the same year. She also had a major retrospective at Tate Modern in London in 2017 which travelled to the Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle in Berlin in 2017-2018.

Sotheby’s is honoured to present this portrait, painted only three years prior to Fahrelnissa Zeid’s death. It is a testament to a rich life – both social and artistic; a true product of the many influences, cultures and people she came to know and befriend throughout a colourful and rich set of experiences.