19th Century European Art

19th Century European Art

Property from a Private Collection

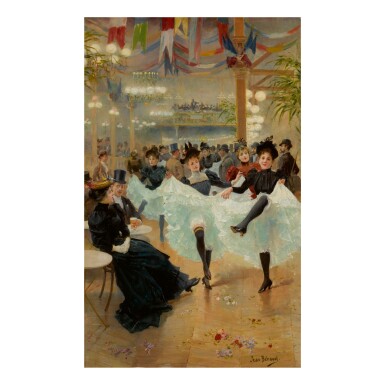

JEAN BÉRAUD | LE CAFÉ DE PARIS

Auction Closed

January 31, 04:23 PM GMT

Estimate

300,000 - 500,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from a Private Collection

JEAN BÉRAUD

French

1849 - 1935

LE CAFÉ DE PARIS

signed Jean Béraud. (lower right)

oil on panel

21⅝ by 13⅝ in.

54.9 by 34.6 cm

Sale: Sotheby's, New York, October 26, 1983, lot 67, illustrated

Sale: Hôtel Drouot, Paris, December 10, 1985, lot 30, illustrated

Richard Green, London (by 1986)

Sale: Sotheby’s, New York, May 23, 1989, lot 96, illustrated

Galerie Pierre Levy, Paris (acquired by 2003)

Marc Gaillard, Paris au XIX. siècle, Paris, 1981, p. 253, illustrated

Patrick Offenstadt, Jean Béraud 1849-1935, The Belle Époque: A Dream of Times Gone By, catalogue raisonné, Cologne, 1999, p.199, no. 231, illustrated

Paris, Galerie Charpentier, Deux Siècles d’Élégances 1715-1915, 1951, no. 304 (as Composition)

Roslyn Harbor, New York, Nassau County Museum of Art, La Belle Époque and Toulouse-Lautrec, June 8-September 7, 2003, n.n. (lent by Galerie Pierre Levy)

In his scrupulous pursuit to record the life of Belle Époque Paris, Jean Béraud was a frequent fixture at the city’s private entertainments (see lot 411), where he recorded the interaction of fashionable guests, and in the public spaces of cafes, balls, and theaters. In a series of celebrated compositions, Béraud portrayed the open-air concerts at the Alcazar and Ambassadeurs, especially popular in the summer heat, and captured the grand stage of the Théâtre des Variétiés from the seclusion of its private boxes. While identified as the Café de Paris in Patrick Offenstadt’s catalogue raisonné, the architecture of this tall columned space— with France’s tricolor flag and multicolored swags hanging from the ceiling, tiers of glowing glass lights, and a band playing for the teeming crowd— more closely resembles one of Paris' cafés-concerts or music halls such as the Folies Bergère (fig. 1). These multi-purpose, bustling establishments offered food, drink, entertainment, and the opportunity to see and be seen. The spaces were so prevalent by the late nineteenth century that the writer Gustave Coquiot remarked in 1896, “the café-concert is undeniably the school of keen observation, a celebration and serenading of the contemporary. Having become a feature of everyday life, cafés-concerts appeared everywhere; it seems that they satisfy everybody’s needs and so fulfill their social role, their truly rare degree of suitability” (Gustave Coquiot, Les cafés-concerts, Paris, 1896, p. 13 as quoted in Jane Kinsman, "Paris Intense," Paris in the Late 19th Century, exh. cat., National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1996-1997, p. 24). For the relatively affordable price of a drink, guests could linger for hours, no fine clothing or refined manners required. Such diversity is depicted in Béraud’s composition, an illustration of a contemporary observer’s record of the “types” that frequented the café-concert from “respectable members of the middle-classes accompanied by their wives…; jolly shop keepers of ruddy complexion; shop assistants hungry for distraction and amusement; single men at a loss for what to do with their evening; sweet girls looking for a heart of gold; students opposed to affection; women overseers serving as mentors for dizzy young girls, apprentices… each enters without fuss, just as they were in the street, with a hat, stick or umbrella in hand, overcoat and scarf” (André Chardourne, Les cafés-concerts, Paris, 1889, p. 14-6, as quoted in Kinsman, p. 28).

As the cafés-concerts often featured both dining and a show, small tables could be moved and repositioned to accommodate the evening’s entertainment, such as the iconic cancan. As at the Folies Bergères, where the cancan was performed directly on the dance floor (versus a stage), in the present work five performers dance inches away from the crowd, holding up their skirts to reveal white petticoats or jupons, their high kicking legs encased in black silk tights held by suspender belts, above which the white frilly pantalons flash. As shown here, the dancers begin with “the mill,” in which they lift their skirts, raise one leg, and hop on the other leg spinning the raised foot in a circle (Jonathan Conlin, Tales of Two Cities, Paris, London and the Birth of the Modern City, Berkeley, California, 2013, p. 163).

The iconic steps of the cancan are believed to have evolved from the final figure in the quadrille, a social dance for four couples. While men originally participated in the dance at public dance-halls, as it became more popular, women eventually dominated as professional performers. With its energetic movement and high kicks, the cancan initially had a scandalous reputation until, in 1850, Celeste Mogador, a star of the Bal Mabille (which Béraud also painted), embraced the dance and provided the entertainment with a certain respectability; by the 1880s, La Goulue (the stage name of Louise Weber) and Grille d’Egout became internationally recognized cancan celebrities. Joining Béraud in capturing the energetic dancers and their equally lively environment were his contemporaries such as George Seurat and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who famously captured Jane Avril high-kicking with abandon.