Classic Photographs

Classic Photographs

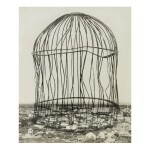

KANSUKE YAMAMOTO | REMINISCENCE

Auction Closed

October 3, 04:15 PM GMT

Estimate

20,000 - 30,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

KANSUKE YAMAMOTO

1914-1987

REMINISCENCE

possibly ferrotyped, signed and with annotation 'TSG Catalogue #93' by Toshio Yamamoto, the photographer's son, in pencil and the photographer's credit, copyright, and estate stamps, dated '53,' in pencil on the reverse, cornered to a mount, embossed, stamped, and annotated 'TSG Catalogue #93' by Toshio Yamamoto in pencil on the mount, framed, 1953

12¼ by 10 in. (31.1 by 25.4 cm.)

Judith Keller and Amanda Maddox, eds., Japan's Modern Divide: the Photographs of Hiroshi Hamaya and Kansuke Yamamoto (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013), pl. 70 (this print)

Legend of a Buddhist Temple (by Kansuke Yamamoto)

a birdcage without a bird and

from a garden without a birdcage with a bird

countless sparks rise up

like a Hindu saint’s apocalypse

along the line of the white Coliseum

shaking the even more grotesque Colossus

sending a sign of the night’s festival

the body writhes like a hummingbird

leaning a cheek on the fingers of a heathen

giving a fierce numbness

(from Kokaku, 1940)

Attentive to international developments in artistic practices of his time, Yamamoto incorporated Surrealism and photocollage into his work from the early 1930s. It is important to note, however, that ‘. . . Yamamoto did not cavalierly adopt the expressive technique of collage from the European avant-garde; he did not use collage for merely its aesthetic and stylistic elements. Rather, he was able to show that this technique was well suited for sharp social criticism, and he used it in the specific context of Japan’ (Japan's Modern Divide, Ryuichi Kaneko, p. 164). He conveyed his political views and critique of contemporary Japanese society through his creative output, which included photographs, poems, newspaper articles, translations and his teaching, and strongly believed in Surrealism as a powerful political weapon.

The birdcage is a recurring motif in Yamamoto’s photography and poetry. He thought of the bird as the most advanced of all beings because it has the ability and freedom to fly. The present image of the cage, its rusty bars mangled and burned, is overlaid on a Japanese city to create an image evocative of the devastating aftermath of the atomic bomb. As ‘housing’ for an animal, the cage is connected to the human houses underneath, alluding to the entrapment of the unseen population of the city below. In this work and many of his other Surrealist photocollages, Yamamoto communicates his frustration with the Japanese state of mind, regulations of freedom and free expression, and the postwar occupation of U. S. military forces. Despite its often somber implications, Yamamoto’s bird/birdcage symbolism perhaps carries some hopeful undertones. The cage in the photocollage as well as in the poem above, is decidedly empty; no bird is caught inside, suggesting that there is hope for Japan and its people. ‘Yamamoto was trying to wake up Japan in order to encourage it to dream’ (Ibid., Amanda Maddox, p. 202).