Art of Africa, Oceania and the Americas

Art of Africa, Oceania and the Americas

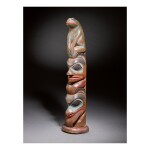

HAIDA MODEL TOTEM POLE

Auction Closed

May 13, 08:41 PM GMT

Estimate

50,000 - 70,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from a Private Collection, London

HAIDA MODEL TOTEM POLE

Height: 28 ¾ in (73 cm)

George T. Emmons, collected in situ in 1880

Museum of the American Indian-Heye Foundation, New York (inv. no. 5/4217), acquired from the above in 1916 with funds from Harmon W. Hendricks

Julius Carlebach, New York, acquired from the above by exchange in 1944

Maria Martins, New York and Paris, acquired from the above by the late 1940s

Private Collection, by descent from the above

Sotheby's, New York, June 24, 2004, lot 23, consigned by the above

Private Collection, London, acquired at the above auction

Totem poles are monumental sculptures carved from great trees, usually cedar, by several Indigenous cultures along the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Symbols of a family’s clan origins, wealth and prestige, as well as the reputation of the carver, they most likely developed from other monumental carving traditions - including house posts, funerary containers and memorial markers. Standing in front of the lineage house, the totem pole was usually the tallest and most complex of the crest poles. Believed to have been developed by the Haida, totem carving most likely spread first to the Tsimshian and Tlingit and then later through British Columbia and Northern Washington.

Access to iron and steel – which may have first arrived as nails found in driftwood and slightly later with European explorers and traders – allowed a people with an existing carving tradition to create larger and much more detailed poles and other carved items with relative ease. In addition, the fur trade gave rise to a tremendous accumulation of wealth. Wealthy leaders commissioned sculptors to represent their social status and the importance of their families and clans, and much wealth was spent and distributed in lavish potlatches which were frequently associated with the construction and erection of totem poles.

In addition to their heraldic function related to clan lineage, these poles were also created to illustrate stories, to commemorate historic persons, to represent shamanic powers, as well as to provide objects of public ridicule. The most widely known tales, like those of the exploits of Raven or of Quats who married the bear woman, are familiar to almost every native of the area. Carvings which symbolize these tales (images of a bird with a long, massive and sharply tapered beak, or of a man whose head is being devoured by a bear) appear both on lineage poles as well as on story poles, the figures sufficiently conventionalized to be readily recognizable even by persons whose lineage did not include them in their own legendary history.

Following the tragic depopulation of the region in the second half of the 19th century, Haida sculptors directed their skills towards the production of miniaturized versions of the traditional forms, as tour-de-force objects in portable format which carried the classical forms to a new audience.

The present post was collected by George Thorton Emmons (June 6, 1852-June 11, 1945) in 1880. Emmons was a U.S. Navy lieutenant, pioneering ethnographer, and collector of art and artifacts from southeastern Alaska. His naval duties brought him to Alaska during the 1880s and 1890s, where he found himself in close contact with the Tlingit and Haida people. There, he gained a thorough respect and understanding for the native cultures. In addition to befriending local leaders, Emmons was able to record specialized Tlingit traditions including including Chilkat weaving, bear hunting and the aforementioned potlach (or communal feast) ritual. The immense amount of knowledge he gained resulted in an invitation to accompany the Alaskan exhibit at the World’s Columbian Exhibition from 1891-1893. In addition to his ethnographic pursuits, Emmons began purchasing Alaskan art and artifacts. Part of his collection was sold to the American Museum of Natural History, the Heye Foundation and the Field Museum in Chicago. in New York, with another going to the These acquisitions constitute the cornerstone of each institution’s holdings from this part of the world. His writings were posthumously published by Frederica de Laguna in the 1991 publication, The Tlingit Indians.