Art of Africa, Oceania and the Americas

Art of Africa, Oceania and the Americas

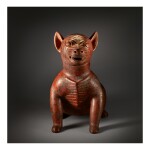

COLIMA SEATED DOG PROTOCLASSIC, CIRCA 100 BC-AD 250

Auction Closed

May 13, 08:41 PM GMT

Estimate

50,000 - 60,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from an American Private Collection

COLIMA SEATED DOG PROTOCLASSIC, CIRCA 100 BC-AD 250

Length: 15 ½ in (39.4 cm); Height: 12 ¾ in (32.3 cm)

D. Daniel Michel, Chicago acquired in 1957 (inventory no. 57:029)

Ancient Art of the New World, New York, acquired from the above

American Private Collection, acquired in 1991

PUBLISHED

The Arts Club of Chicago, Catalogue to the Exhibition, Chicago, 1957, cat. no. 16

Alan R. Sawyer, Animal Sculpture in Pre-Columbian Art, Chicago, 1957, p. 9

Richard F. Townsend, The Art of Tribes and Early Kingdoms, Selections from Chicago Collections, Chicago, 1984, Fig. 39

The Arts Club of Chicago, Chicago, 1957

The Art Institute of Chicago, Animal Sculpture in Pre-Columbian Art, October 12, 1957–February 2, 1958

The Art Institute of Chicago, The Art of Tribes and Early Kingdoms, Selections from Chicago Collections, January 12-March 4, 1984

Dogs are the most frequently depicted animal in the corpus of Colima effigy vessels, yet the wrinkled dog such as this figure, is a much rarer depiction of the type. The typical reddish brown burnished surface aptly conveys the hairless Mexican dog called the xoloitzcuintle (xolo for short). The name xoloitzcuintle comes from the Aztec language and combines the canine-deity “Xolotl” with the word for dog, “itzcuintle.” Xololt is depicted with canine traits, and was meant to accompany the dead in their journey through the dangers of the underworld up into the night sky to dwell with one’s ancestors. Here, the deep wrinkles on the flank and face of the present example give this dog a fierce, taut and animated appearance, a fitting image for an animal being a guide of the underworld.

The modern Huichol people of Northwest Mexico have a slightly modified association between dogs and funerary rituals. They believe that a small dog impedes the soul from finding its way to its ancestors. In order to pacify this canine, the deceased must provide sustenance, hence explaining the practice of burying the dead with food (Kristi Butterwick, Heritage of Power, New York, 2004 p. 66). Butterwick relays one account of the journey to the land of the Huichol ancestors: “Fire one comes to where there is a dog…It stands there, that dog, as if it is tied up. It is barking there. It is as if wants to bite that soul as it tries to pass…That is why, when one of us dies, we make little tortillas for him to take along, little thick tortillas. They are put in a bag…so that he can feed that dog. The dog says to that soul, ‘Give me something to eat now so I may let you pass’…[That little dog] is from ancient times. It died and then it remained there, to stand watch on that road….[The soul] takes the tortillas out of the bag [and when] the dog is busy eating…that soul can pass and it keeps walking.” (Ramon Medilla Silva, in Stacy B. Schaefer and Peter T. Furst, eds., People of the Peyote, Albuquerque, 1996, pp. 392-4).

For similar examples see accession no. 1983.93.1 in the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco see, and accession no. 2007.345.4 in The Metropolitan Museum of Art.