American Art

American Art

Property from the Teron Collection, Canada

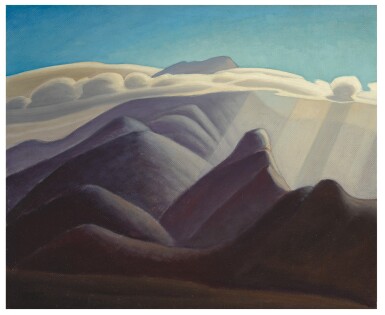

LAWREN STEWART HARRIS | IN THE WHITE MOUNTAINS II

Auction Closed

November 19, 04:22 PM GMT

Estimate

250,000 - 350,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from the Teron Collection, Canada

LAWREN STEWART HARRIS

1885 - 1970

IN THE WHITE MOUNTAINS II

signed LAWREN/HARRIS (lower left); also signed again and titled In the White Mountains II (on the reverse)

oil on Masonite

18 by 22 inches

(45.7 by 55.9 cm)

Painted circa 1934-35.

Dominion Gallery, Montreal, Canada

Sold: Christie’s, Ottawa, Canada, April 30, 1970, lot 53

Acquired by the present owner at the above sale

Among Canada’s most celebrated modernist painters, Lawren Harris created enduring images that remain icons of the country’s National identity. Known for grand vistas of Lake Superior, the Rocky Mountains and the Arctic, rendered in rich gradients of hue bound by graphic forms, Harris continuously tested limits of creative and mystical expression. The meditative In the White Mountains II was painted during his transitional period in New Hampshire, at the precipice of an awakening that led to his embrace of symbolist abstraction.

Harris found inspiration in every landscape he encountered, both urban and rural, but his visits to the United States caused pivotal shifts in his development. In addition to his years in Hanover, New Hampshire and Santa Fe, New Mexico, his early trip with painter J.E.H. Macdonald to the landmark 1913 exhibition at Buffalo’s Albright Knox Gallery, Contemporary Scandinavian Painting, inspired them to define a new artistic vision for Canada. Upon their return to Toronto they formed The Group of Seven - of which Harris was the unofficial leader - whose ambition was united by spiritual convictions to represent the vast northern landscape with modern techniques and a bold, luminous palette. At a time when the newly formed country was barely connected, they traveled by rail, box car, canoe and on foot, painting small, but expressive oil sketches on site and expanding them into vivid canvases back in the studio. They criss-crossed the country, exhibited regularly and continue to be rewarded with national and international recognition.

By the early 1930s, however, Harris almost stopped painting entirely as he struggled to express his complex metaphysical ideas through landscapes. As he explained to his friend, fellow artist Emily Carr: “We have not yet learned nor made use of one billionth of what nature has for us - as a people - and we need it. Profoundly to me, is the interplay in unity of the resonance of mother earth and the spirit of eternity. Which though it sounds incongruous, means nature and the abstract qualities fused in one work” (June, 1930). While Harris was intrigued by the possibilities of abstraction that were being developed in Europe and the United States, conservative audiences in Toronto proved hostile. In 1926, his friend Fred Hausser had praised members of the Group for not allowing “themselves to become putterers in a blind alley of professional abstraction,” while another critic wrote: “Abstraction is not a natural form of art expression in Canada” (as quoted in Atma Buddhi Manas: The Later Work of Lawren S. Harris, Dennis Reid, The Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 1985, p. 18).

His ambitions were not deterred. Harris aligned himself with pioneering artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Arthur Dove and Wassily Kandinsky, many of whom he exhibited with as a member of the Societe Anonyme at the The International Exhibition of Modern Art at The Art Gallery of Toronto in 1927. Indeed, the present work is reminiscent of O’Keeffe’s paintings of Lake George (fig. 1), and Dove’s landscapes of the 1930s. Like these artists, Harris maintained a lifelong interest in Theosophy, and in 1933 presented his treatise Theosophy and Art, his third piece published in The Canadian Theosophist. The same year he left his wife, Trixie, to be with Bess Hausser, fellow Theosophist and artist, scandalizing Toronto society. The oppressive social and artistic expectations of Toronto pushed Harris and Bess into exile and they fled to New Hampshire in 1934, where Harris’ uncle was a professor at Dartmouth. The move invigorated them both. As Bess emphatically wrote to her friend back in Canada, painter Doris Mils: “While that was seething it was impossible to do any creative work, although one saw so much that fairly invited paints and brushes. - Perhaps to say that we are both starting to work now will tell you more than anything else” (November 14, 1934).

Painted during this fertile time of experimentation, the present work is a rare distillation of the many influences that Harris was engaged with, and a tribute to the distinctive landscape of the Northeast. Carefully composed, the dark base of the mountains powerfully grounds the celestial atmosphere, their peaks reminiscent of the free-form icebergs he had painted in the Arctic. The foregrounded mountain is anthropomorphized, with its face illuminated by stylized rays striking the valley beyond. In this sense, it is an optimistic landscape, and points to the visual language of abstraction which he feverishly pursued over the next three decades.