19th Century European Paintings

19th Century European Paintings

Property from a Private Collection

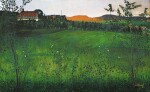

HARALD SOHLBERG | Modne Jorder (Ripe Fields)

Auction Closed

December 11, 03:18 PM GMT

Estimate

1,000,000 - 1,500,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

Property from a Private Collection

HARALD SOHLBERG

Norwegian

1869 - 1935

Modne Jorder (Ripe Fields)

signed Sohlberg lower right; titled in Norwegian on the reverse

oil on canvas

73 by 116cm., 28¾ by 45¾in.

Haakon Pettersen (commissioned from the artist. Pettersen, 1867-1937, was a businessman and an owner of the Gunerius Pettersen company. His country home at Rotnes farm in Nittedal is the setting for the present work)

Daggen Schram

Einar Sohlberg (son of the artist; acquired from the above)

Acquired by the family of the present owners by the 1950s; thence by descent

Arne Stenseng, Harald Sohlberg: En kunstner utenfor allfarvei, Oslo, 1963, opp. p. 32, illustrated in colour (and dated 1891); p. 135, illustrated (hanging in the Sohlberg room at the Norwegian Jubilee Exhibition in 1914); p. 195, no. 30, catalogued (as Modne jorder)

Øivind Storm Bjerke, Harald Sohlberg, Oslo, 1991, p. 24, cited (as one of Sohlberg's 'hovedverker', major works); p. 89, illustrated (with erroneous dimensions and date); p. 259, cited

Kristiania (Oslo), Statens Kunstutstilling, Høstutstillingen, 1898 (15de), no. 115

Stockholm, Kungliga Akademien för de fria konsterna, Utställning af norska konstnärers arbeten, 1904, no. 218

Copenhagen, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Den norske Udstilling Charlottenborg Efteraaret, 1906, no. 253 (as Rotnæs, dated 1893; one of seven works by Sohlberg exhibited)

Vienna, Künstlerbund Hagen, Norwegische Künstler, 1912, no. 203

Kristiania (Oslo), Norges Jubilæumsutstilling, 1914, no. 395

San Francisco, Panama-Pacific International Exhibition, 1915, no. 116

London, The Royal Society of British Artists galleries, Exhibition of Norwegian Art, 1928, no. 189

Oslo, Kunstnernes Hus, Høstutstillingen, 1932, no. 265

Oslo, Kunstforening, Harald Sohlberg, 1971, no. 9

Oslo, Galleri K, Harald Sohlberg, 1986, no. 3, illustrated in the catalogue

London, Hayward Gallery, Dreams of a Summer Night; Paris, Petit Palais, Lumières du Nord; Oslo, Nasjonalgalleriet, Nordiske stemninger, 1986, no. 87 (London); no. 110 (Paris); no. 107 (Oslo)

Sandvika, Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, Harald Sohlberg, 1991

Modum, Blaafarveværket, Nordiske Stemninger: Harald Sohlberg, L.A. Ring, 2003, no. 55

Oslo, National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design; London, Dulwich Picture Gallery; Wiesbaden, Museum Wiesbaden; Harald Sohlberg, 2018-19, no. 24, illustrated in the catalogue (as Ripe Fields, 1898)

Painted in 1898, Ripe Fields is a seminal work in Sohlberg's career. The painting has long been recognised as pivotal, announcing the first full flourishing of the artist’s highly personal style, deployed in order to give full expression to a landscape he had first encountered some seven years earlier.

The painting is a masterful example of Sohlberg's glazing technique. This and the precisely balanced composition lend the scene its strong initial impact, which is followed by meticulous details which reveal themselves gradually. The glowing, enamel-like finish of the emerald green ‘ripe field’ is set against the finely observed foliage in the foreground. Each leaf is articulated with a layer of rich impasto, acting as a repoussoir for the verdure beyond. Vertical tree branches to the left and right frame the scene, while in the distance a track punctuated by pale-trunked birch trees at rhythmic intervals runs across its width. On the horizon, the central swathe of the hillside blazes with the first light of the day. These elements, within a pure landscape devoid of the human figure, define Sohlberg’s finest works. The importance that Sohlberg attached to Ripe Fields is emphasised by its appearance, reversed, in the artist's self-portrait painted in Paris in 1896 (fig. 1).

In early 1891 Sohlberg spent several months staying with the family of Gunerius Pettersen at their estate at Rotnes farm in Nittedal, near Oslo. Coming soon after he had completed his training at the National College of Art and Design of Oslo (then known as Kristiania), and only two years after his first experience painting independently at Valdres, the stay earned Sohlberg an early commission from the Pettersens to paint the present work. Two oil studies depicting Rotnes in winter are known from this time. While the smaller study for Ripe Fields is dated 1891, Øivind Storm Bjerke argues that the genesis of this composition is in fact somewhat later. Sohlberg is known to have taken the smaller study with him to Paris and worked on it there in 1895-96. It was perhaps to commemorate the time working at Rotnes, and emphasise the importance of the composition to him at an early stage, that Sohlberg postdated the study '1891'. While it is not dated, it is likely the present work had only recently been finished when Sohlberg first exhibited it at the Autumn exhibition in 1898.

Three years after Edvard Munch's final public exhibition in Oslo, Sohlberg made his breakthrough at the Oslo state exhibition in March 1894 with the landscape Night Glow. The work was identified by art historian Jens Thiis as the only one in the entire exhibition that stood out as being original and surprising. Bought by fellow artist Eilif Peterssen, the painting was then acquired for the National Gallery in Oslo. This success catapulted Sohlberg to prominence, and led to the travel grant that allowed him to go to Paris soon after. Spurred on by support from collector and patron of the arts Olaf Schou among others, Sohlberg subsequently travelled in 1899 to the Rondane mountains. His legendary experiences there inspired Winter Night in the Mountains: an icon of Norwegian art, the 1914 version is a highlight of the collection of the Oslo National Gallery (fig. 2).

Throughout his career Sohlberg was regularly compared with his illustrious compatriot Edvard Munch. While this was no doubt to his credit, Sohlberg consistently denied being influenced by Munch, six years his senior. Superficially their style is rather different: Sohlberg's precise, accomplished draughtsmanship - magnificently deployed in the present work - is clearly at odds with the expressive brushstroke of his compatriot. Sohlberg's own form of Synthetism, inspired by continental Symbolism and the stemningsmaleri or 'mood-painting' which characterised Nordic art at the close of the nineteenth century, also had less of a psychological component than Munch's. Yet as Øivind Storm Bjerke has argued, 'both Munch and Sohlberg helped to establish a trend towards simplified palettes dominated by just one or a few colours - frequently white, black, blue, red or green - which helped to emphasise atmosphere and mood'. Certainly the present work bears comparison with Munch's Moonlight, a pure landscape from the same period (fig. 3). An exhibition exploring the artists' relationship was held in New York in 1995, titled Munch/Sohlberg: Landscapes of the Mind.

Confirming the high regard in which Sohlberg held Ripe Fields, the present work was included in no fewer than eight international exhibitions during his lifetime, including in the Norwegian Jubilee Exhibition in 1914 (fig. 4).

We are grateful to Øivind Storm Bjerke for his assistance in cataloguing this work.