- 1147

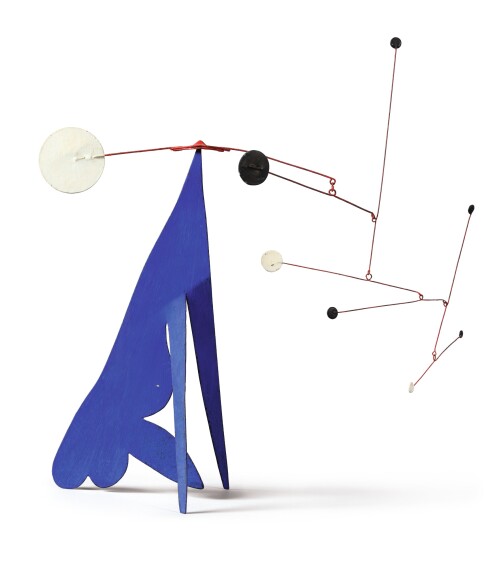

ALEXANDER CALDER | Black and White and Red on Blue

Estimate

3,500,000 - 5,000,000 HKD

Log in to view results

bidding is closed

Description

- Alexander Calder

- Black and White and Red on Blue

- incised with the artist's monogram and dated 56 on the largest element

- sheet metal, wire and paint

- 16 7/8 by 16 3/4 by 6 in. 42.9 by 42.5 by 15.2 cm.

Provenance

Perls Galleries, New York

Private Collection, Florida

Sotheby's, Los Angeles, 22 January 1973, Lot 11

Solomon & Co., New York

Private Collection, Pennsylvania (acquired from the above in 1974)

Private Collection, Munich (acquired from the above in 1993)

Thence by descent to the present owner

This work is registered in the archives of the Calder Foundation, New York, under application number A08223.

Private Collection, Florida

Sotheby's, Los Angeles, 22 January 1973, Lot 11

Solomon & Co., New York

Private Collection, Pennsylvania (acquired from the above in 1974)

Private Collection, Munich (acquired from the above in 1993)

Thence by descent to the present owner

This work is registered in the archives of the Calder Foundation, New York, under application number A08223.

Catalogue Note

Calder does not suggest movement, he captures it … he imitates nothing, and I know no art less untruthful than his.

Jean-Paul Sartre

A synthesis of precision, balance, and movement, Alexander Calder’s Black and White and Red on Blue situates between the realms of allusion and abstraction. Executed in 1956, the standing mobile comprises a constellation of small metal discs delicately suspended in space. The architectonic abstract shapes are arranged in a series of natural biomorphic forms: the blue base suggests a zoomorphic body with two perched legs, sitting to attention, while the cascading spindly metal wires are comparable to bones in a spine or a limb. The assemblage allows the work to reach out like the cantilevered branches of a tree arced gently in the breeze, arousing a quiet sensation of delight. The influence of the dynamics of the natural world on Calder’s artistic practice led him to declare in 1951: “The underlying sense of form in my work has been the system of the Universe, or part thereof. For that is a rather large model to work from” (Alexander Calder, “What Abstract Art Means to Me”, Museum of Modern Art Bulletin 18, No. 3, Spring 1951, n.p.). At the slightest gust of wind, the sculpture awakens, transforming from its state of inertia into a swaying, bewitching kinesis. Toing-and-froing in a gentle, rhythmic dance, Black and White and Red on Blue is enchanting to behold and entrancing to observe.

Calder was born in Pennsylvania, USA, in 1898 to a family of artists: his father and grandfather were each renowned sculptors, and his mother was a portrait painter. Determined to pave his own way, Calder experimented with unconventional methods and mediums, challenging the classical training of his forefathers in order to forge a radical artistic language. His is not an art laden with anguish, nor ruled by the confines of tradition; rather, Calder’s sculptures are imbued with a revitalising sense of dynamism, vigour and ingenuity, reflective of the artist’s personality. The art of Calder, once remarked Marcel Duchamp, is “pure joie de vivre. [It] is the sublimation of a tree in the wind” (Marcel Duchamp, ‘Alexander Calder’, Collection of the Société Anonyme, New Haven 1950, online). Before embarking on a career as an artist, Calder enrolled at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, to study mechanical engineering. He was a talented mathematician, and his four-year degree instilled him with a thorough mastery of tools, industrial design, and the characteristics of metal. While these qualities later played a role in the creation of his sculptures, Calder’s approach to art was intuitive, capturing the spontaneity of nature and immersing its viewer in an enthralling visual experience. As curator Penelope Curtis asserts, “Calder will find a way of making the spell last, embedding the unpredictable, contradictory, (and often syncopated) movements of animals and people into his works” (Penelope Curtis, “Performance of Post-performance”, in Exh. Cat., London, Tate Modern, Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture, 2015, p. 17).

In 1952, a few years before the present work was created, Calder was awarded first prize for sculpture at the Venice Biennale, marking a period of great international acclaim for the artist. The migration of painterly shapes from canvas into physical space situated Calder at the forefront of the avant-garde: utilising his background in engineering, Calder captured with all the precision of a carefully hand-assembled machine the ambitious, utopian moment of post-war America. At the same time, Calder remained indebted to the artists he befriended and exchanged ideas with during his time in Paris between 1926 and 1933. Echoing the momentous text by Albert Einstein, Calder’s Mobiles and Stabiles espouse a spatio-temporal coupling, uniting time and space in equilibrium, removing painting’s constituent parts from the atemporal canvas, and placing them in the universal continuum. As Einstein writes: “before the advent of the theory of relativity, time played a different and more independent role, as compared with the space coordinates. It is for this reason that we have been in the habit of treating time as an independent continuum” (Albert Einstein, Relativity: The Special and the General Theory, New York, 2004, p. 47). It is this decisive transition from the formal rigidities of painting to the ‘real’ contingencies of sculpture that differentiated Calder from his École de Paris influences.

As one of the most important sculptors of the Twentieth Century who greatly influenced a generation of artists through his pioneering investigations into kinetic sculpture, Calder enjoyed a close and fruitful friendship with the Surrealist painter Joan Miró. Although their works developed along separate trajectories, they often experimented with the same vibrant palette and simple economy of line: indeed, the present standing mobile could almost have sprung from the canvas of one of Miró’s biomorphic abstract paintings, or vice versa. In title and composition alike, Black and White and Red on Blue simultaneously evokes a natural creature and its own intrinsic abstract materiality. Dreamily it flits between the two, in a triumphant celebration of a singular marriage of art, science, and the natural world. As succinctly observed by Jed Perl: “Although Calder was not quite the first or the last artist to set sculpture in motion, he sent volumes moving through space with more conviction and imaginative power – with more eloquence and elegance – than any other artist has. These are the works of a poet, but a poet guided by the steady instincts of a scientist” (Jed Perl in Exh. Cat., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Calder and Abstraction, from Avant-Garde to Iconic, 2013, p. 36).

Jean-Paul Sartre

A synthesis of precision, balance, and movement, Alexander Calder’s Black and White and Red on Blue situates between the realms of allusion and abstraction. Executed in 1956, the standing mobile comprises a constellation of small metal discs delicately suspended in space. The architectonic abstract shapes are arranged in a series of natural biomorphic forms: the blue base suggests a zoomorphic body with two perched legs, sitting to attention, while the cascading spindly metal wires are comparable to bones in a spine or a limb. The assemblage allows the work to reach out like the cantilevered branches of a tree arced gently in the breeze, arousing a quiet sensation of delight. The influence of the dynamics of the natural world on Calder’s artistic practice led him to declare in 1951: “The underlying sense of form in my work has been the system of the Universe, or part thereof. For that is a rather large model to work from” (Alexander Calder, “What Abstract Art Means to Me”, Museum of Modern Art Bulletin 18, No. 3, Spring 1951, n.p.). At the slightest gust of wind, the sculpture awakens, transforming from its state of inertia into a swaying, bewitching kinesis. Toing-and-froing in a gentle, rhythmic dance, Black and White and Red on Blue is enchanting to behold and entrancing to observe.

Calder was born in Pennsylvania, USA, in 1898 to a family of artists: his father and grandfather were each renowned sculptors, and his mother was a portrait painter. Determined to pave his own way, Calder experimented with unconventional methods and mediums, challenging the classical training of his forefathers in order to forge a radical artistic language. His is not an art laden with anguish, nor ruled by the confines of tradition; rather, Calder’s sculptures are imbued with a revitalising sense of dynamism, vigour and ingenuity, reflective of the artist’s personality. The art of Calder, once remarked Marcel Duchamp, is “pure joie de vivre. [It] is the sublimation of a tree in the wind” (Marcel Duchamp, ‘Alexander Calder’, Collection of the Société Anonyme, New Haven 1950, online). Before embarking on a career as an artist, Calder enrolled at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, to study mechanical engineering. He was a talented mathematician, and his four-year degree instilled him with a thorough mastery of tools, industrial design, and the characteristics of metal. While these qualities later played a role in the creation of his sculptures, Calder’s approach to art was intuitive, capturing the spontaneity of nature and immersing its viewer in an enthralling visual experience. As curator Penelope Curtis asserts, “Calder will find a way of making the spell last, embedding the unpredictable, contradictory, (and often syncopated) movements of animals and people into his works” (Penelope Curtis, “Performance of Post-performance”, in Exh. Cat., London, Tate Modern, Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture, 2015, p. 17).

In 1952, a few years before the present work was created, Calder was awarded first prize for sculpture at the Venice Biennale, marking a period of great international acclaim for the artist. The migration of painterly shapes from canvas into physical space situated Calder at the forefront of the avant-garde: utilising his background in engineering, Calder captured with all the precision of a carefully hand-assembled machine the ambitious, utopian moment of post-war America. At the same time, Calder remained indebted to the artists he befriended and exchanged ideas with during his time in Paris between 1926 and 1933. Echoing the momentous text by Albert Einstein, Calder’s Mobiles and Stabiles espouse a spatio-temporal coupling, uniting time and space in equilibrium, removing painting’s constituent parts from the atemporal canvas, and placing them in the universal continuum. As Einstein writes: “before the advent of the theory of relativity, time played a different and more independent role, as compared with the space coordinates. It is for this reason that we have been in the habit of treating time as an independent continuum” (Albert Einstein, Relativity: The Special and the General Theory, New York, 2004, p. 47). It is this decisive transition from the formal rigidities of painting to the ‘real’ contingencies of sculpture that differentiated Calder from his École de Paris influences.

As one of the most important sculptors of the Twentieth Century who greatly influenced a generation of artists through his pioneering investigations into kinetic sculpture, Calder enjoyed a close and fruitful friendship with the Surrealist painter Joan Miró. Although their works developed along separate trajectories, they often experimented with the same vibrant palette and simple economy of line: indeed, the present standing mobile could almost have sprung from the canvas of one of Miró’s biomorphic abstract paintings, or vice versa. In title and composition alike, Black and White and Red on Blue simultaneously evokes a natural creature and its own intrinsic abstract materiality. Dreamily it flits between the two, in a triumphant celebration of a singular marriage of art, science, and the natural world. As succinctly observed by Jed Perl: “Although Calder was not quite the first or the last artist to set sculpture in motion, he sent volumes moving through space with more conviction and imaginative power – with more eloquence and elegance – than any other artist has. These are the works of a poet, but a poet guided by the steady instincts of a scientist” (Jed Perl in Exh. Cat., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Calder and Abstraction, from Avant-Garde to Iconic, 2013, p. 36).