- 12

Imogen Cunningham 1883-1976

Description

- Imogen Cunningham

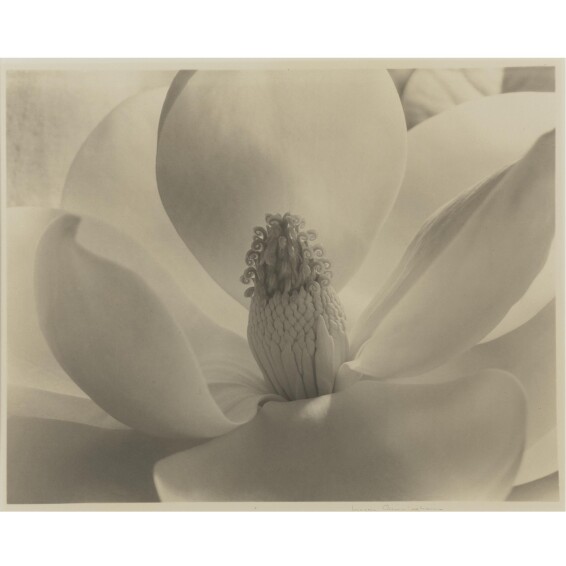

- 'formen einer blume' (magnolia blossom)

Provenance

The photographer to a California artist and illustrator

By descent to the present owner

Literature

Other prints of this image:

Richard Lorenz, Imogen Cunningham: Flora (New York, 1996), pl. 11

Richard Lorenz, Imogen Cunningham: Ideas without End (San Francisco, 1993), pl. 38

Richard Lorenz, Imogen Cunningham: the Modernist Years (Tokyo, 1993), unpaginated

Margery Mann, Imogen Cunningham: Photographs (Seattle, 1970), pl. 11

William A. Ewing, Flora Photographica: Masterpieces of Flower Photography (New York, 1991), pl. 77

Condition

In response to your inquiry, we are pleased to provide you with a general report of the condition of the property described above. Since we are not professional conservators or restorers, we urge you to consult with a restorer or conservator of your choice who will be better able to provide a detailed, professional report. Prospective buyers should inspect each lot to satisfy themselves as to condition and must understand that any statement made by Sotheby's is merely a subjective qualified opinion.

NOTWITHSTANDING THIS REPORT OR ANY DISCUSSIONS CONCERNING CONDITION OF A LOT, ALL LOTS ARE OFFERED AND SOLD "AS IS" IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CONDITIONS OF SALE PRINTED IN THE CATALOGUE.

Catalogue Note

The photograph offered here, a large, early print of Imogen Cunningham's Magnolia Blossom, is one of a handful of images most responsible for the photographer's present reputation, as it was in her own lifetime. Like Tower of Jewels (Lot 9), also a study of the Magnolia grandiflora, the elegant, open Magnolia Blossom, with its full frame of petals, stamens, and pistils, reveals Cunningham's dual passions for both the science and aesthetics of the camera. The photograph's beautifully rendered textures and larger-than-life shapes testify to Cunningham's skill in translating the vibrant object before her camera onto photographic paper. This revelatory aspect of her best botanical work brought Cunningham international fame in the 1929 Film und Foto exhibition in Stuttgart, where this image was among the works included. The print of the Magnolia offered here, on matte-surface paper, and accompanied by the photographer's Mills College label, represents the best possible state of the image.

Cunningham began her photographic career as a turn-of-the-century Pictorialist. Her soft-focus figure studies, however, concealed a rigorous training in the science of photography. After receiving her degree in chemistry at the University of Washington, she won a scholarship to Germany in 1909, where she trained at the Technische Hochschule in Dresden. Her thesis there was an analysis of self-manufactured platinum papers. Returning to Seattle, she opened her own studio, where she took portraits and posed tableaux in the Pictorialist vein. As early as 1910, however, and continuing into that decade, she began to explore the natural world with her camera, and in this she was part of a larger trend. By 1920, photographers in both the United States and in Europe were beginning to shift away from the artistic photography of the fin-de-siècle and move toward a more realistic, 'objective' vision. In Germany, this vision was exemplified by the Neue Sachlichkeit and the work of Albert Renger-Patszch, whose articles on plant photography Cunningham is likely to have known. Her successive simplification of flower forms in the early 1920s was her own breakthrough into modernism, and put her in the good company of such like-minded photographers as Edward Weston and Ansel Adams. Separately, and together, they would re-examine their own philosophy of photography, a re-examination that would culminate in the unadorned aesthetic of Group f/64.

In her series of magnificent plant photographs from 1925--including her famous magnolia studies, as well as the leaves of a banana plant and the sensuous calla, among others--Cunningham achieved a mixture of precision and beauty that won her international fame. In these studies, Cunningham elevates whole or parts of flowers to icon status, producing images that are almost hypnotic in their power. Dramatically lit and monumentally composed, the plants in these photographs have a vitality that transcends the still frame. This aliveness is nowhere more apparent than in the magnolia image offered here: once a magnolia begins to blossom, there is only a small window of time in which a photograph such as Cunningham's can be made. The first petals begin to fall away as others open, producing a full flower for only a day or two, and in certain temperatures, less than a day. The perfection of the image offered here represents an achievement of calculation, as well as aesthetics. This powerful delicacy was not lost on Edward Weston, who praised Cunningham's work and her botanical studies especially. Working with his famous shells in 1927, Weston described the difficulty of balancing the beautiful, rounded nautilus for his camera. 'One of these two new shells when stood on end,' he wrote in his daybook, 'is like a magnolia blossom unfolding' (Daybooks, California, 28 April 1927).

It was Edward Weston who, when asked to choose American photographers for Stuttgart's landmark Film und Foto exhibition of 1929, included Cunningham in his selection. This international exhibition of avant-garde photography was one of the most influential shows of its type, fostering many photographers' international reputations and defining progressive trends in photography for the next half century. The ten submissions by Cunningham comprised a nude study, an industrial photograph, and eight iconic botanicals. Magnolia Blossom, titled in the exhibition 'Formen einer Blume,' was included not only in this international show, but in other European venues well. Fluent in German and attuned to the role of photography on the international stage, Cunningham often retained the German title for this and other images from that time, including the photograph offered here.