- 10

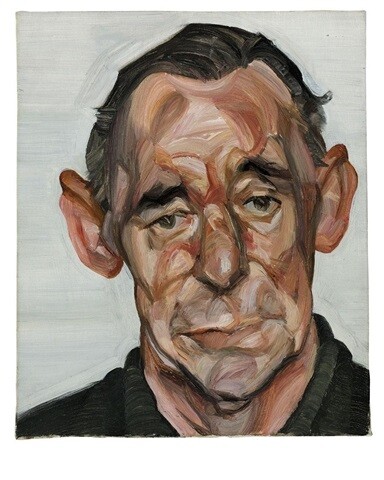

Lucian Freud

Description

- Lucian Freud

- John Deakin

- oil on canvas

- 30.2 by 24.8cm.

- 11 7/8 by 9 3/4 in.

- Executed in 1963-64.

Provenance

Roberto Shorto, London

Frank Lowe, London

Sale: Christie's, London, Contemporary Art, Part I, 25 June 1997, Lot 25

Acquired directly from the above by the present owner

Exhibited

London, Hayward Gallery; Bristol, City Art Gallery; Birmingham, City Museum and Art Gallery; Leeds, City Museum and Art Gallery, Lucian Freud, 1974, p. 49, no. 91, illustrated

Washington D.C., Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden; Paris, Musée National d'Art Moderne; London, Hayward Gallery; Berlin, Neue Nationalgalerie, Lucian Freud Paintings, 1987-88, no. 28, illustrated in colour

London, National Portrait Gallery, John Deakin, 1996, p. 9, illustrated in colour

Kendal, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Lucian Freud: Paintings and Etchings, 1996, p. 28, no. 8, illustrated in colour

London, Tate Britain; Barcelona, Fondació 'La Caixa'; Los Angeles, Museum of Contemporary Art, Lucian Freud, 2002-03, no. 52, illustrated in colour

Venice, Museo Correr, Lucian Freud, 2005, p. 63, no. 11, illustrated in colour

Literature

Robert Hughes, Lucian Freud Paintings, London 1993, no. 28, illustrated in colour

Bruce Bernard & Derek Birdsall, Lucian Freud, London 1996, no. 108, illustrated in colour

Robin Muir, John Deakin: Photographs, London 1996, p. 9, illustrated in colour

Catalogue Note

“I paint people not because of what they are like, not exactly in spite of what they are like, but how they happen to be.” (Lucian Freud cited in: William Feaver, Lucian Freud, London 2002, p.15)

Freud’s desire to “portray with profundity the people that interest me” is nowhere better realised than in his remarkable portrait of photographer John Deakin - the infamous chronicler of the closely-knit School of London group. Deakin himself was a leading figure in the post-war Soho Bohemia frequented by Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews, and was quick to spot the genius of the painters of his acquaintance. “Being fatally drawn to the human race," Deakin shared in their desire to explore the psychology of his human subjects through portraiture. “What I want to do when I take a photograph is make a revelation about it. So my sitters turn into my victims. But I would like to add that it is only those with a daemon, however small and of whatever kind, whose faces lend themselves to being victimised at all.” (Robin Muir, A Maverick Eye: The Street Photography of John Deakin, London 2002, p. 11)

Initially working as a fashion photographer for Vogue until his chronic alcoholism, notorious rudeness, and frequent loss of photographic equipment got him fired - reports came back from the Vogue studios of fallen tripods, crying models and exasperated fashion editors - Deakin eventually turned his eye to the portrait commissions at which he excelled. His photographs give an intimate record of the notoriously reclusive inner circles of the School of London; in part because they provided the basis for much of Francis Bacon’s portraiture. Bacon felt unable to inflict the painterly injuries dealt by his hand in front of his models directly so he commissioned Deakin to take photographs of some of his closest friends and models – among them Muriel Belcher, Isabelle Rawsthorne, Frank Auerbach and Freud himself. Upon Bacon’s death in 1992, these paint-splattered photographs still littered his studio; long after Deakin himself had died of heart failure in 1972. An individual who had his own aspirations to be a painter, Deakin constantly down-played the art of photography reserving special scorn for his colleagues at Vogue. Bruce Bernard said of Deakin that “unfortunately he didn’t care much for what he did best, and I’m sure he resented the fact that it was just that. Perhaps never believing in photography’s ultimate refinements gave him his cutting edge.” (ibid., p.10)

Freud’s portrait of John Deakin was executed at the end of a period that saw a sea-change in the way he painted, and it masterfully demonstrates the evolution of his mature style. Leaving behind the idiom which had made him “the Ingres of Existentialism”, as Herbert Read famously described him at the time of his exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1955, Freud began to cultivate a fresher, more vigorous artistic practice that became his signature style. As he has said “I wanted to develop something unknown to me.” (cited in: William Feaver, Lucian Freud, Milan 2005, p.35) This change in style importantly coincided with a number of visits Freud paid to collections in Europe with the intention of seeing works by specific painters. He travelled to Colmar in Alsace for Grünewald, to Montpellier for Courbet, to Montauban for Ingres, to Castres for Goya and perhaps most notably, to Haarlem, in 1962 for an exhibition of work by Frans Hals. It was with Hals that Freud became especially enamoured: “When he lights up something or twists something,” he said, “I’ve never seen an unnecessary mark. His amazingly fluid and immediate way of painting, his sense of life absolutely fraught.” (cited in: William Feaver, Lucian Freud, Milan 2005, p.35)

Hals’ brushwork helped persuade Freud to change his painterly technique, notably by changing brushes. Swapping his fine sable brushes for ones made of dry, more springy hog’s hair enabled him to develop his portraits from the flatter style he favoured earlier into one in which layers of paint acquire a tactile quality. This granted his portraits the rhythm and contours of a landscape painting. The brush-strokes become starkly apparent, the oil visible on the surface. A further new technical aspect of Freud’s painting is also at play in this work, namely, the use of Cremnitz white, an unusually heavy, granular pigment Freud had begun to use for flesh. Together these innovations enabled Freud to paint every detail in the face with such exactitude that, combined with the intimate scale of the work, seems akin to a scientist in his laboratory examining a specimen under a microscope. “Sometimes,” Freud said, “when I’ve been staring too hard, I’ve noticed that I could see the circumference of my own eye.” (cited in: William Feaver, Lucian Freud, London 2002, p.28)

Deakin in this portrait was descirbed by William Feaver as, “a faintly rueful-looking Iago.” (William Feaver, Lucian Freud, London 2002, p.30) His protruding ears and large nose are here depicted with an almost clinical frankness. While the muscles and tendons beneath the skin also have a quasi-anatomical vitality, Freud adds to this a disquietingly intimate degree of psychological insight. By placing the head slightly off-centre – a recurrent device in his work – Freud makes Deakin seem quite vulnerable, just as he had in his 1952 portrait of Francis Bacon. A heavy drinker, Deakin had the melancholic demeanour of a man grown accustomed to life with a permanent hang-over, and here Freud captures him with his guard down. The slight arch of the left eyebrow gives Deakin an air of curiosity belied by the detached, introspective glazed-over expression in the eyes. Freud has given painterly voice to his description of Deakin – “like Cinderella and the Ugly Sisters at the same time.” (Lucian Freud cited in: Ron Muir, A Maverick Eye: The Street Photography of John Deakin, London 2002, p. 13)

The product of much soul-searching on the part of both painter and sitter, Freud gathers into this portrait a powerful psychological penetration that is intensified by the intimate scale of the work. Deakin’s character is stripped-bare; he is as “naked” as are the sitters in Freud’s vast nudes. This meditative painting epitomises Freud’s stated task as an artist: to make the viewer feel slightly uncomfortable and yet hold our gaze by involuntary chemistry.