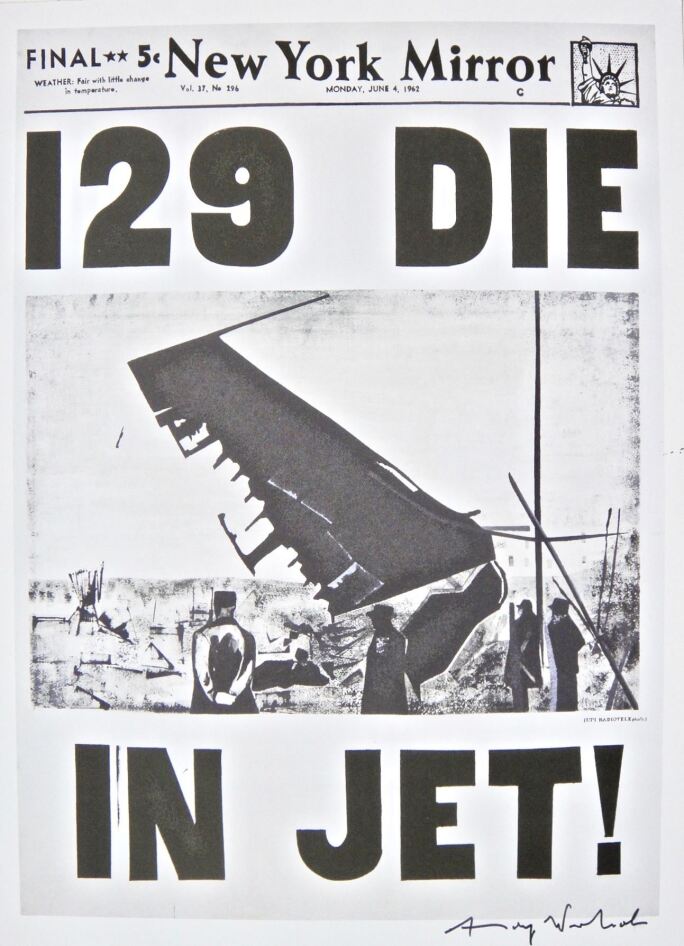

I n June of 1962, Andy Warhol met his friend Henry Geldzahler, for lunch at Serendipity, famously one of his favorite and regular New York restaurants. Geldzahler, a young curator, offered some advice for the budding Pop artist, whose work at the time dealt with Coke bottles and soup cans. "It's enough life, it's time for a little death," Geldzahler reportedly suggested to Warhol. Geldzahler’s encouragement to move beyond standard brands and consumer logos to engage with more serious subject matter inspired the artist to create some of the most powerfully radical artwork of his career. Among Warhol’s first confrontations with the theme of death were 129 Die in Jet!, his 1962 reproduction of a New York Mirror front page, as well his earliest portraits of the late Marilyn Monroe. Moving into 1963, Warhol quickly advanced beyond these oblique references to confront fatality squarely in its grim face through the operation of silkscreen. He had embarked on what would later be known as the Death and Disaster series.

Sustaining the shrewd cultural commentary behind his seminal Pop Art canvases such as 32 Campell’s Soup Cans, which launched him into the art world in the early 1960s, Warhol explored a darker side of American life in the middle of the century with his Death and Disaster series. This loosely connected group of roughly seventy artworks takes as their subjects car accidents, suicides, electric chairs, even contaminated cans of tuna fish that were reported to kill two housewives in the Detroit suburbs. Warhol avidly appropriated his source material from newspapers and police photo archives, manipulating the industrial silkscreen technique to mechanically repeat these lurid images across broad swaths of canvas. In this daring detournement, Warhol created an endlessly haunting psychological portrait of American popular culture by focusing on its morbid fascination with violence and tragedy.

Within the broader Death and Disaster series, the Car Crash paintings that Warhol made between late 1962 and early 1964 form the most extensive and variegated group of pictures. Drawing on six different documentary source photographs of separate automobile accidents, Warhol’s Car Crash paintings examine the quotidian reality yet sensational spectacle behind the mass-media broadcast of everyday death. White Disaster (White Car Crash 19 Times) is the largest single panel Car Crash painting Warhol ever executed, and it stands out for its expansive white surface that resembles the lamina of mass-produced newspaper. Warhol’s impersonal rendering on canvas of a found newspaper photograph – one that remains unidentifiable to this day – totally silences the faceless subject by suspending him in perpetual anonymity, even while dramatizing the cinematic finality of his death.

Other famous projects within Warhol’s Death and Disaster series echo with the same deafening silence that are made palpable in his early flashing reproductions of the car collision. His Suicides paintings recreate media photographs of figures mid-leap from a high-rise building, suspended in gravity and yet on the verge of imminent suicidal death. Meanwhile, in his large-scale Electric Chair paintings from 1964-1965, Warhol frequently added blank canvases spaces to mirror the printed image of the execution device, adding a compositional expanse of emptiness that reiterates the injunction to silence within the charged space of the death chamber. Finally, his Late Disasters series reproduce fewer but larger images to convey more detail with a sense of disparate irony, as in his Ambulance Disaster paintings that reveal how an ambulance vehicle intended to save lives ultimately becomes an instrument of death itself.

Apart from Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster), which set the auction record for Andy Warhol at the time of its sale at Sotheby’s New York in 2013 and shares the same source imagery as White Disaster (White Car Crash 19 Times), some of the largest Disaster paintings are held in prestigious museum collections – owing no doubt to their importance in 20th century art. These paintings stand as important cornerstones of the Pop Art holdings of each of the museums to which they belong. Orange Car Crash 14 Times entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, in 1991 as a gift from architect Philip Johnson. Meanwhile, other prominent examples include Black and White Disaster #4 (5 Deaths 17 Times in Black and White) which has resided in the esteemed Kunstmuseum Basel and Pink Race Riot [Red Race Riot], which has been housed at the Museum Ludwig since 1976.

Cascading down the monumental canvas to evoke the lamina of newsprint and the cinematography of filmstrips, the silkscreened image in White Disaster (White Car Crash 19 Times) speaks to Warhol’s preoccupation with ideas of death within the cultural context of the news media zeitgeist. Warhol’s Death and Disaster paintings most powerfully tests his own famous hypothesis when he said in an ARTNews interview in 1993 that “The more you look at the same exact thing, the more the meaning goes away.” As we behold Warhol’s Death and Disaster paintings, the original macabre of Warhol’s source imagery may seem to evaporate, but the legendary artist’s timeless artistic achievement never cease to persist with auratic intensity.

![View 1 of Lot 114: White Disaster [White Car Crash 19 Times]](https://sothebys-com.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/e455da9/2147483647/strip/true/crop/5788x7817+0+0/resize/278x376!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fsothebys-md.brightspotcdn.com%2F55%2F5d%2Fc2cc6e514132ba30657ee377bdcb%2Fwarhol.jpg)