T extiles are a visual language for many cultures, and are far more revealing than first meets the eye.

The first time I went to India, one of the first places I went to visit was the Craft Museum in Delhi. The Craft Museum is one of the most exciting and special places in the city. Large dimmed rooms are filled by collections of painted panels, embroidered textiles and saris from all the states of India. In this exceptional atmosphere you experience the feeling of being entirely enveloped by a new world, a world made from the perfect stitches of endless embroideries and the miniature brush strokes on painted panels, where beautiful stories are forever retold and kept alive. It’s easy to be captivated by this world, which although exotic at first sight, is strangely reminiscent of a decorative vocabulary you already know.

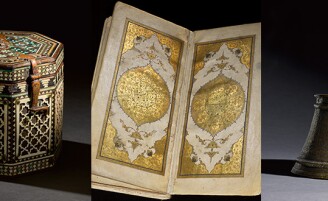

I have a particular passion for Mughal textiles. I adore the use of colour, the stylised, almost geometric depictions of nature, and the very natural order of the motif repeats. This fascination is thanks to the unknown artist. The embroiderer leaves their own individual mark, whilst still making sure that each stitch is more perfect than the reality depicted. It is difficult to find this individuality, as the embroiderer’s aim is to make the object as close a reflection to the real world as possible.

The H. Peter Stern Collection of Mughal and Ottoman textiles in the forthcoming Arts of the Islamic World & India auction takes me back to an Islamic museum in Istanbul, gazing upon ottoman velvets with the cintamani design, and of course the famous tulip motif itself. I love how textiles are so indigenous to their place of origin, but can also be so quickly and easily assimilated by other cultures. Looking at certain Ottoman designs there are surprising similarities to 17th century European textiles (lots 170 and 171 for example). Textiles are unique. In a way, like paintings, they are works of art, but they are made to be used. They are born for a special use, like the wonderful ones used for tents. The Mughal qanat (lot 143) in this sale is particularly beautiful, grand and yet still cozy, sheltered and warm.

There is a special relationship between the human and the painted cloth. At first glance simply decorative, textiles, upon further inspection, lose any decorative connotation and take on a more profound meaning that goes beyond the aesthetic. Your eyes can’t help but get lost in them. Never imposing, textiles instead organically accompany the environment in which they are placed. Textiles tell a story, sometimes a very personal one, the story of the land in which they were made. Now, more than ever, they make your eye travel to a beautiful faraway place, this is their beauty.