I still own a rather battered copy of a slim paperback, published on the eve of the Second World War, entitled Art in England. I have kept it as a relic, not because I enjoy reading it. Illustrated with just "32 photogravure plates", it includes a short and mostly disparaging essay on English art from the Middle Ages to the start of the twentieth century, written by none other than the then-director of the National Gallery, Kenneth Clark, who concluded his micro-survey with the apologetic remark that "we are, after all, a literary people." It is hard to believe now, but until about fifty years ago this was the prevailing attitude towards English art, and indeed British art in general: perennially second-rate and condemned to remain so, given that the genius of the nation was inclined to words rather than images.

When did this misplaced preconception begin to crumble? I think the process started in the 1960s and early 1970s, when the monumental achievements of a number of senior British artists of that time (notably Henry Moore and Francis Bacon) had become impossible to ignore; while a number of younger artists, David Hockney among them, were breaking irresistibly into the mainstream of international contemporary art.

The impetus did not come from British art alone, but also from British popular music, many of whose leading figures started out as art students and whose work habitually married performance with visual spectacle in all kinds of unpredictable ways - from the Rolling Stones smashing their guitars on stage in emulation of Gustav Metzger, the inventor of Auto-Destructive Art, to the shape-shifting stage personae adopted by David Bowie during the course of his career. If it had not been for the battles fought and won by those earlier generations of British artists (and artistes) I suspect that the passage to fame and fortune of Damien Hirst and his generation, and the accompanying recognition of London as a powerhouse city of the contemporary art world, would have been considerably more difficult to accomplish.

"This is Tomorrow: Works from the David Ross Collection" and "Made in Britain" are two sales that trace the evolution of British art from its postwar (and more specifically Sixties) renaissance to the present day, the assembled lots amounting to a frequently dizzying, vibrant refutation of the old idea that the English (let alone the British) are innately inhibited in the field of the visual arts.

What could be more dizzying and vibrant than Bridget Riley's series of sense-stunning screenprints on Plexiglas from 1965 - explorations, still raw with the sense of experiment, in the direction of what was soon to be enshrined (in rather anaemic artspeak) as Op Art? Even today it is difficult to know quite what to make of these distorted matrices or networks of line, twisted and rotated in pictorial space so as to induce a jarring sense of dislocation or unease. It is as if Mondrian's utopian grid has been strangely and abruptly warped, so purged of colour and reconfigured with such salutary violence that if it expresses an idea of the city (as Mondrian's often did) then that city is a place of vertiginous, disquieting energy. And if it expresses an idea of the self (which seems equally plausible) then that self is one subject to extreme shifts in mood and consciousness, liable to plunge into a void of uncertainty at any moment. The power and strangeness of Riley's early work seems to grow rather than fade with the passing of time.

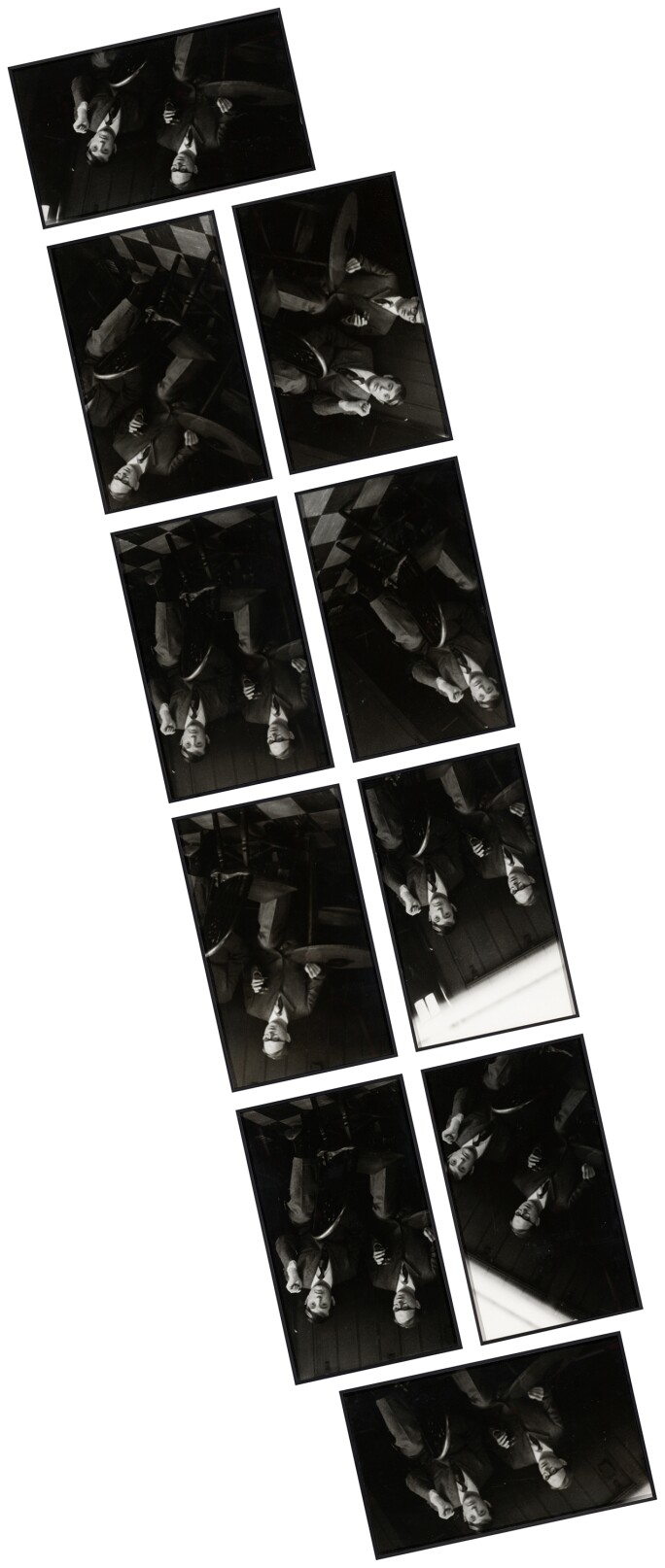

Equally disquieting, albeit in a very different way, is Gilbert & George's Head Over Heels, one of a series of photographic-cum-performance works known as the Drinking Pieces, created by the artists in their studio in East London in the early 1970s. Dressed in their trademark flannel suits and dark ties they appear before the camera, in a wood-panelled room surely reeking of booze, in ten black-and-white snapshots. Their faces are appropriately blurred (they are supposed to be drunk, after all), and they appear as if caught in the middle of some discontinuous conversation on a theme that shall remain forever mysterious.

The whole thing of course is a performance, in which they are simultaneously themselves but not themselves, acting out a parodic version of an England that amuses them but also fundamentally oppresses them: an England of bankers and civil servants and weekend golf, of stiff upper lips and emotional guardedness; an England that only lets itself go under cover of darkness, or under the influence. Much the same England, in fact, that the young David Hockney railed against in his vivid, graffiti-like paintings of the early 1960s; but whereas Hockney escaped to California, Gilbert & George preferred to stay where they were, fuelled by their own exhilarating anxiety. As if to emphasise the sense of disequilibrium at the centre of their work, they even stipulated that all ten photographs that constitute Head Over Heels be hung on the wall at an angle off straight - making it literally the most lopsided of all the Drinking Pieces. If there is such a thing as English Dadaism, this is surely it.

The spirit of iconoclasm was strong in British art of the 1960s and 1970s. Nowhere was it more powerfully in evidence than in the work of Anthony Caro, who was the first British sculptor to turn away from traditional carving and modelling - to abandon, in particular, the tradition of monumental bronze sculpture so formidably occupied by Henry Moore - and work instead with the oxyacetylene torch and the welding kit. Caro's chosen material was steel, the same steel used in the construction of skyscrapers and much of the rest of the infrastructure of the modern metropolis, and he used it in its nakedly industrial forms - the i-beam, the girder, the pole and the sheet - to create assemblages or configurations of metal that sat directly on the floor.

His ambition, he said, was to create sculpture that did not look down on people from the literal and moral height of a plinth, but that could be met with face to face as in a conversation. Caro's no-nonsense approach to making art has often been linked to the formalist ideas of the American art critic Clement Greenberg - in particular, his belief that it was the destiny of every art form to be reduced to its barest and most essential qualities, so that (for example) painting should have nothing sculptural about it and sculpture should never stray towards the pictorial.

Floor Piece Aleph (Flowerhead) of 1970 is a fascinating piece, in part because it shows just how far Caro was prepared to depart from the very critical orthodoxy he had supposedly embraced: in its conjuring up of the energies (and colour) of a flower, in its (extremely pictorial) evocation of a flower's pistils, it does an awful lot of things that formalist sculpture was never supposed to do. All the more interesting is the fact that such a quintessential example of Caro's capacity for lyricism was once owned by none other than Clement Greenberg himself, who acquired it directly from the artist at a time when they were particularly close. Strong evidence here (if any were needed) of the gap between theory and practice, and also perhaps of that between a critic's writings and a critic's taste.

"No one could be more English than I am," Walter Sickert once mischievously declared: "Born in Munich in 1860, of pure Danish descent!" Sickert was thumbing his nose at the very idea that art (or people for that matter) should aspire to some presumed standard of ethnic purity; and it was surely no coincidence that he made the remark in the 1930s, when Hitler's poisonous ideas about race were so much in the air. Sickert's painting was as defiantly mongrel as its creator, with its parentage equally in the Paris of Degas and the London of Jack the Ripper; and the same has been true of much British art since, which no doubt helps in part to explain the breadth of its horizons. (Gilbert of Gilbert & George, it is worth remembering, was born in northern Italy, in a region of the South Tyrol so remote that his mother tongue was not even Italian but the obscure local dialect of Ladin.)

Oscar Murillo (born in Colombia) is a British artist through and through in Sickert's terms, and his painting Manifestation of 2018-19 is perhaps in part a manifestation of precisely what those terms are. Manifestation is one of a series of pictures created from fragments of earlier paintings that have been sewn together, in a process that also involves covering some pieces of canvas with paint and then transferring the colour to other fragments like ghostly imprints or palimpsests. The resulting image, intricately formed from many parts, each with a different origin, yet woven and shaped into a whole, becomes both a metaphor for the layered, joyously impure nature of all human culture or civilisation - and indeed every human being - while simultaneously evoking the visual language of protest, graffitied walls and the like. I see it as a way of painting the truth that Sickert once put into words, and painting it with anger as well as wit.

Magdalene Odundo is another artist born overseas (in Kenya) to have enriched British art immeasurably with a wealth of cross-cultural influences - some her birthright, others acquired along the way. Brought up in Nairobi and Mombasa, she moved to the United Kingdom in 1971 to study graphic and commercial arts, discovered a love of making pots, made studio visits to Bernard Leach and then Matthew Cardew before going on to hone her skills at the Pottery Training Centre in Abuja, Nigeria - and she has scarcely looked back since.

I first met her in the early 1980s, when I was a young would-be art critic and she was starting out. She was in fact the first real live artist I ever interviewed (lifelong regret: I never bought anything from her at the time!), and it seemed obvious to me even then that she was an extraordinarily gifted maker of things. In those less enlightened times she was described as a ceramicist or potter, rather than an artist, although the passage of time has made it clear that she is indeed a uniquely gifted artist who just happens to express herself by making pots. Untitled (A Large Vase) of 1992 is an exceptional example of her work. Hand-built rather than thrown, in the Gbari method she learned in Nigeria, richly glazed in colours that run from dark brown to burnished gold, it strikes me as as a vessel that contains more than any ordinary vessel should or could do: some indefinable essence of a human being, surely a woman, captured in the swell and tapering of its forms, long-necked, heavy-bellied, pregnant with life.

Having already written too much about not enough, I only have room to make brief mention of two more works that catch my eye. I admire the elegant restraint of Ryōan-ji (for John Cage) by Edmund de Waal, who happens to be another ceramicist-artist with overseas connections (grandfather: Dutch). And I am impressed by Tony Bevan's powerful and monumental canvas Red Interior, a brooding, cathedral-like depiction of the artist's own studio, envisaged as a space that is somewhere between a chapel and a prison. I suspect quite a few artists see their own studios in the same light.

Finally, looking back at this brief and all too partial account of some of the sales' highlights, I cannot help being struck by how very different all the works of art and artists I have picked out are, one from one another, in almost every sense: whether it be creative intention, gender or cultural origin. Perhaps this simply reflects the contents of these particular sales, but I suspect there is more to it than that. The truth is that the tremendous vitality of British art since around 1960 has been inextricably linked to its heterogeneity. Breadth is not always the opposite of depth: sometimes it can be the cause of it.