I

n 1981, as the outline for Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus began to take shape in his mind, Francis Bacon had good reason to celebrate. Against all odds, he had outlived his ‘three score and ten’, and despite numerous brushes with ill health and sadistic lovers, he retained much of his youthful appearance and physical vitality. Bacon could still paint all morning, carouse wildly with friends late into the night and be back at work in his studio again while his drinking companions were dead to the world. The artist was also at the pinnacle of his creative powers: with hundreds of tumultuous paintings already achieved and possibly as many others destroyed, he had arrived at a highly focused, starkly simplified late period. ‘The few things that matter,’ as Bacon himself put it, ‘become so much more concentrated and can be summed up with so much less.’[1]

Bacon’s prodigious energy and discipline ensured that his imagination worked at white heat, even with a hangover, which he said made his mind ‘crackle with electricity’; and he would describe how one image after another seemed to surge up as he manipulated the fluent medium of oil paint on the rough canvas. Each new twist in the impasto was a raid on the unknown that might, the artist hoped, create an image of such force that it would ‘cancel out’ everything he had done before. For Bacon, devotee of the roulette table and the risky love affair, this is where the stakes were at their highest. With a single, angry brushstroke, he could strike a mound of inert pigment into life or obliterate a beautiful half-formed head beyond recall[2]. Decades of trial and error had taught the master artificer how to take full advantage of his daring: the sudden streak of white unloosed over a crimson background, a delicate studding of green and black into ruddy flesh.

Against all odds again, as if he were a lone voice amid babbling fools, Bacon’s preoccupation with violence, tragedy and death had brought him international fame. Over the previous decade, his career and reputation had gone from strength to strength. Shadowed though it was by the death of his lover, George Dyer, Bacon’s retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris was the culmination of everything he had striven for. He laid down a challenge to his lifelong mentor and hero, Picasso, in the same grand galleries that the Spaniard had occupied before him, and he was wildly acclaimed both by the Parisian intelligentsia and the grand public. Big exhibitions around the world, including a show focused on his recent work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1975, amply confirmed this new degree of recognition.

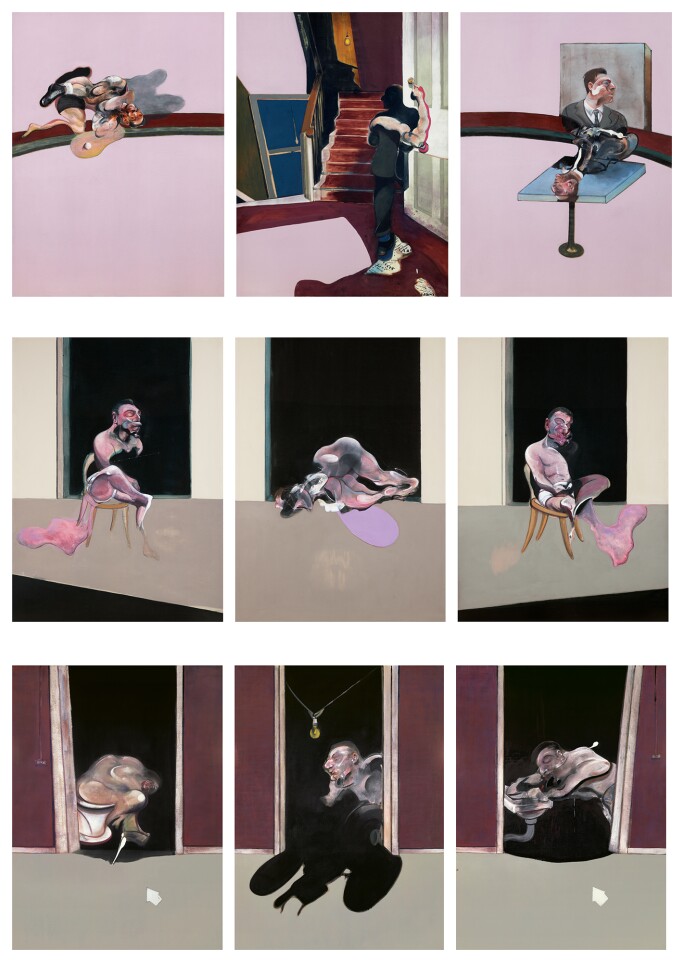

(Tate Collection, London(; Triptych May-June 1973, 1973, (Collection of Esther Grether, Art © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. / DACS, London / ARS, NY 2020)

Bacon was also working his way through an intensely traumatic theme: Dyer’s suicide in the hotel room they had been sharing in the lead-up to the Grand Palais exhibition. Although he appeared to take both this catastrophe and the fanfare of his Paris opening in his stride, Bacon was to experience lasting remorse over the death of the much younger man who had been his lover and muse since the early 1960s. In an attempt to commemorate Dyer as well as to exorcise his feelings of guilt, Bacon made painting after painting in memoriam, including a series of ‘black’ triptychs culminating in Triptych, May-June 1973, which relates Dyer’s last moments in images of poignant, point-blank directness[3]. Bacon had been visiting Paris frequently during this period and, as from 1974, he began working for extended periods of time in a studio beside the Place des Vosges, as if he sought to relive the tragic event at close quarters while transforming it into art. The ‘black’ triptychs can be seen as specifically focused on a personal tragedy which the artist was compelled to atone for. But the obsession with the themes of guilt and expiation was never to leave him, to the extent that these themes became the essential subject of his art, taking on an increasingly universal significance that culminated in Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus.

[Bacon's] obsession with the themes of guilt and expiation were never to leave him, to the extent that they became the essential subject of his art, taking on an increasingly universal significance that culminated in 'Triptych Inspired by the ‘Oresteia’ of Aeschylus.'

From the beginning of his career, Bacon had pursued only the grandest themes that probed the nature of man and the meaning of human existence most deeply. In art he was drawn to the peaks of achievement alone, from Egyptian sculpture through Michelangelo, Rembrandt and Velázquez to Picasso, just as his interests in literature ranged from Greek tragedy through Shakespeare to Proust, Joyce and Eliot. Paradoxically for an avowed atheist, Bacon was drawn time and again to religion and myth, principally, he said, because they provided him with a structure through which he could best express complex, intimate emotions of his own. The breakthrough work that first brought him to public attention, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion of 1944, conflates Christian and Greek myth, since the figures themselves, inspired by Bacon’s discovery of classical tragedy, represent the avenging Erinyes or Furies who, as in Aeschylus’s drama, pursue Orestes once he has murdered Clytemnestra, making him guilty of the grave sacrilege of matricide[4].

Despite his patchy schooling, Bacon had developed a fascination for Aeschylus early on. It is likely that this sophisticated interest came indirectly from seeing a performance of T. S. Eliot’s The Family Reunion when it was first performed in London in 1939, probably at the suggestion of his older, more cultured companion of the time, Eric Hall. Like the Oresteia by which it is partly inspired, Eliot’s play is concerned with guilt, whether real or imagined, and expiation[5]. The treatment of that theme struck such a deep chord in Bacon that he went on to read a recondite study entitled ‘Aeschylus in his Style: A Study in Language and Personality’ by W. B. Stanford, a professor of Greek Literature. Certain passages that Stanford rendered into English were to stay with Bacon for the rest of his life, especially the now famous phrase uttered by the Furies as they close around the hunted Orestes hoping to take their revenge: ‘The reek of human blood smiles out at me.’[6] The synaesthetic impact of this phrase on Bacon, as well as Aeschylus’s intensely compounded, highly artificial style in general, cannot be overestimated.

Bacon’s fascination with antiquity was by no means confined to reading commentaries on Greek tragedy, however. He read Aeschylus’s Oresteia in various translations repeatedly, and he may well have been struck that, like his most dramatic paintings, it was constructed as a trilogy (‘Agamemnon’, ‘The Libation Bearers’ and ‘The Eumenides’), just as the relentless Furies manifested as a group of three[7] (vehement non-believer as he was, Bacon accorded the utmost importance to certain numbers[8]).

Antiquity as a whole captivated Bacon. If he esteemed Egyptian art more highly than its Greek counterpart, he knew both well from the collections in the British Museum: he was particularly impressed by the Minoan fresco at Knossos that depicts figures leaping over the horns of the sacred bull (another theme that the artist explored). In 1965, after considerable preparation, Bacon undertook a trip to Athens to visit the Parthenon and the city’s other major cultural sites with George Dyer and his Soho photographer friend, John Deakin, having made a heroic attempt to learn modern Greek. The artist felt so identified with ancient art and literature, in fact, that he at one point declared: ‘In my work I always feel I am following a long call from antiquity’. In a letter to a friend he also mused as to whether the Sibyl at Delphi still ‘gave out’ her enigmatic prophecies[9]. The ancient Greek world view had already struck such a deep chord in Bacon that, by the time he began painting the Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus, his imagination teemed with images that Greek culture had inspired in him.

Yet nothing in Bacon’s oeuvre is ever as simple or clear-cut as these classical interests or ‘influences’ imply. As a self-confessed ‘grinding-machine’ in which everything he saw, read or thought was ground up ‘very fine’, Bacon held an extraordinary range of references subtly and unexpectedly commingled in his mind (as he had already shown spectacularly by fusing the scream of Eisenstein’s nurse with the sternly composed features of the Velázquez Pope). Although they have the central symbol of the Christian faith as their subject, for instance, Bacon’s great ‘Crucifixion’ triptychs of 1962 and 1965 are nevertheless shot through with allusions to the earlier rites and barbarities of Greece – as if the artist could not find all the resonance he needed in the ominous event alone of Christ nailed to the cross (which, significantly, the artist once likened to a ‘self-portrait’). In these masterly evocations of suffering, the ‘reek of human blood’ ‘smiles out’ almost tangibly so suffused are they with crimson gore.

Bathed in blood as Aeschylus’s tragedy is, Bacon’s reinterpretation of it in Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia appears at first sight comparatively restrained, as if the physical horror of the story had been recast on a higher, more abstracted plane. For sure, the middle panel is soaked with a rich red, as if drenched in blood and possibly harking back to the ‘red carpet’ with which Clytemnestra greeted and cunningly ensnared her returning, victorious husband; otherwise there is only the tell-tale trickle of blood seeping under the door and the angry wound in the Fury-like creature on the left of the composition. The restraint, however, is deeply chilling. Slowly and implacably it dawns on the viewer that the very worst has happened. The central figure, no longer human but a spectre X-rayed to the bone, appears to be gnawing at its own innards in a sacrificial bowl, as if preparing some grisly libation to the Gods. Yet this fleshy, Michelangelesque apparition, its neck reduced to vertebrae, could also be seen as welded to a ceramic basin recalling the toilet on which Bacon’s lover, George Dyer, was found dead (as the artist commemorated him in the middle panel of Triptych, May-June 1973). If this interpretation is valid, then it suggests one of the myriad ways the artist found of exploring, and possibly exorcising, deep, private feelings of his own within a transposed mythical structure.

Trails of associations of this kind proliferate once the triptych is more closely analyzed. In the right-hand panel, another, or possibly the same, headless, fleshy figure prepares to depart through an open door into the void beyond. Curiously its body appears to be bisected by the door, with the further half entering a space beyond the picture plane. Meanwhile, both of the figures’ legs taper off into a shadow, like a memory of their presence, on the floor below, while two stunted limbs (or another Fury) manifest themselves on the upper torso. Equally inexplicable is the tubular chair discernible in the left-hand panel’s dark void. This very contemporary piece of furniture, of the kind Bacon himself designed as a very young man, may well have a purely compositional role to play, and it is not difficult to imagine the artist disingenuously dismissing it as ‘just something I needed to break up all the blackness’. More likely though no less mysteriously, the chair evoked certain memories for the artist.[10]

No precise references to the Aeschylean drama can be satisfactorily adduced, however, and this majestic triptych remains essentially impervious to any literal analysis, as Bacon intended, since he wished his images to open up ‘the valves of sensation’, in himself and in those who looked at them, rather than illustrate or suggest a specific ‘story’. Painted not long after the Oresteia triptych, Bacon’s Oedipus and the Sphinx after Ingres (1983) forms another prime example of the way Bacon subverts the aura and trappings of a well-known classical myth to create a vehicle for conveying his own intimate sensations about human fate. Once a painting could be ‘read’ or understood, the artist believed, it was bled of its vital mystery and power. And not the least paradox in Bacon’s universe is that, as a committed atheist, he wanted his works to have all the enduring, imaginative potency of the Sibyl in her cave or saints in their shrine.

Bacon was fully conscious of the difficulties that lay before him as he began to try out variations on the ancient Oresteian myth in his mind. Writing to Michel Leiris, the writer and former Surrealist to whom he had become increasingly close since the latter had written the preface to his Grand Palais exhibition, Bacon intimated that he wanted, as always, to avoid ‘telling a story’. The letter, dated 20 November 1981, was part of an ongoing discussion between the two men about the meaning of ‘realism’ in art. What he hoped to convey, Bacon insisted, was not some kind of illustration of the tragedy but the deep effect it made on him and the images it engendered in his imagination. ‘For me, realism is an attempt to capture … the cluster of sensations that the appearance arouses in me’, he writes. ‘As for my latest triptych and a few other canvases painted after I read Aeschylus, I tried to create images of the episodes created inside me. I could not paint Agamemnon, Clytemnestra or Cassandra, as that would have been merely another kind of historical painting when all is said and done. Therefore, I tried to create an image of the effect that was produced inside me. Perhaps realism is always subjective when it is most profoundly expressed.’ Indeed, Bacon was to add later, all the texts that he found truly interesting were those that triggered the most vivid images in his mind.

‘For me, realism is an attempt to capture … the cluster of sensations that the appearance arouses in me.'

Francis Bacon

Bacon had of course already made a large-scale attempt to convey all the sensations the tragedy evoked in him five years earlier when he painted Triptych 1976. There, against an icy pale blue background, he had enacted episodes from the lugubrious sequence of events, moving from a disturbing, Prometheus-like congruence of birds feeding on human innards to a bright bowl of sacrificial blood. A harsh inevitability dominates the way each panel relates to but disrupts the others in this triptych, as if there were a stasis in the horror and the separate events were doomed to go on repeating themselves for ever. The composition is filled with a variety of references, from the heads resembling a close friend of Bacon’s[11] to clearly delineated Furies, their claws gripping a tubular structure as they wait to pounce on a fresh victim.

By contrast, the Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus radiates an unearthly calm. The cries of rage and terror in Agamemnon’s palace have died down, and we are confronted by the bare facts of the way the terrible curse on the House of Atreus has worked itself out, revenge after revenge, crime by bloody crime. The triptych is presented as a single, simultaneous event, with all the tragic evidence on display. However much the eye darts from panel to panel, seeking some sequential development between them, it is presented with a complete unity, implacable and impenetrable. Already enacted, the hideous story has been taken up by a chorus off-stage and relayed to the outside world. Catharsis, the eventual aim of all Greek tragedy, is under way, and the bloodied images radiate finality as if already enshrined in their own enigma.

Another no less troubling enigma lies deeply embedded in this mysterious triptych. Why, throughout his entire career, did Bacon identify so strongly, so personally, with the themes of crime, expiation and exile? What had brought about his identification with the guilt-ridden Orestes, or with Christ on the cross, to such an extent that those highly charged themes permeated the very texture of his art? Was there an experience or occurrence in his own life that caused him to return so obsessively to studies of intense suffering, as if by recreating it in paint on canvas he could finally free himself of it and escape the hounding of his own Furies?

The Fury portrayed in Bacon’s Oresteia is unusually prominent, clearly delineated and threatening, so we might assume that remorse, the ‘agenbite of inwit’, still holds the artist in its vice-like grip. Bacon himself made frequent hints about his troubled relationship with his father, whom he disliked even though he felt sexually attracted to him, and who, once confronted unequivocally by his son’s homosexuality, banished him from the family home in Ireland to a precarious life in the big European capitals. Was Bacon’s exile and his subsequent guilt occasioned by some crime he thought he had or actually had committed? Had his own adult life not confirmed that guilt by having his first great love, Peter Lacy, die of drink (Bacon thought of it as a suicide), and his second, George Dyer, kill himself? Bacon once admitted that if he hadn’t managed to channel his internal conflict into painting he would have become a complete drunk or a criminal. The artist’s own insistence that his paintings should never tell a ‘story’ is well-known. In retrospect Bacon’s entire oeuvre appears to have fed off a tragedy of his own which was constantly re-enacted, like an obsessive dream, but never disclosed or explained.

As he enters the final phase of his career, however, Bacon appears to focus more and more on resolving the dilemma that had raged at the core of his being. The Oresteia triptych conveys an overwhelming sense of the inevitability of fate and the cruelty of human existence – a vivid enactment of Shakespeare’s ‘As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods; They kill us for their sport’. But it also radiates a new degree of acceptance, of the kind that frequently characterizes the late work of great artists. In it, for the first time in a life consumed by conflict, Francis Bacon seems to have found, if not peace, then a degree of reconciliation with his inner demons.

[1] Interview with Francis Bacon by Michael Peppiatt, Art International, Paris, Autumn 1989

[2] The artist himself was very explicit about this in conversation with David Sylvester: ‘When I was trying in despair the other day to paint the head of a specific person, I used a very big brush and a great deal of paint and I put it on very, very freely, and I simply didn't know in the end what I was doing, and suddenly this thing clicked, and became exactly like this image I was trying to record. But not out of any conscious will, nor was it anything to do with illustrational painting. What has never yet been analyzed is why this particular way of painting is more poignant than illustration. I suppose because it has a life completely of its own. It lives on its own, like the image one's trying to trap; it lives on its own, and therefore transfers the essence of the image more poignantly.’ Interviews with Francis Bacon’, London, Thames and Hudson, 1993, p. 133.

[3] The black bat emanating from the body slumped in the middle panel clearly refers to the bat-winged Furies so central to Bacon’s personal mythology and discussed in detail later in this essay.

[4] Orestes had been impelled to kill his mother because she had murdered his father, Agamemnon, on his victorious return from the Trojan war, for having sacrificed their daughter, Iphigenia.

[5] Bacon’s deep admiration for, and even identification with, Eliot was clearly acknowledged in his Triptych Inspired by T.S. Eliot's Poem ‘Sweeney Agonistes’ (1967), which can be seen as a precursor in a more Modernist idiom to the ‘Oresteia’ triptych.

[6] Bacon also mentioned another phrase from Stanford that describes Clytemnestra brooding over her revenge like a hen.

[7] Dwelling in the Underworld, with snakes entwined in their hair and their eyes dropping blood, each Fury specialized in avenging a different crime.

[8] As an inveterate gambler, Bacon was very aware of numbers as harbingers of good or bad luck. He appeared particularly attached to number seven, and many of the various addresses where he lived include that number or multiplications of it.

[9] Letter to the author, 5 December 1984

[10] In ‘Triptych August 1972’, painted in memory of George Dyer, Dyer is shown seated on a simple, modern chair.

[11] The present author detects a striking resemblance to the photographer Peter Beard in these two heads, while acknowledging that this may be a subjective interpretation.