TO BE SOLD IN VICTORIAN, PRE-RAPHAELITE & BRITISH IMPRESSIONIST ART (LONDON, 12 JULY)

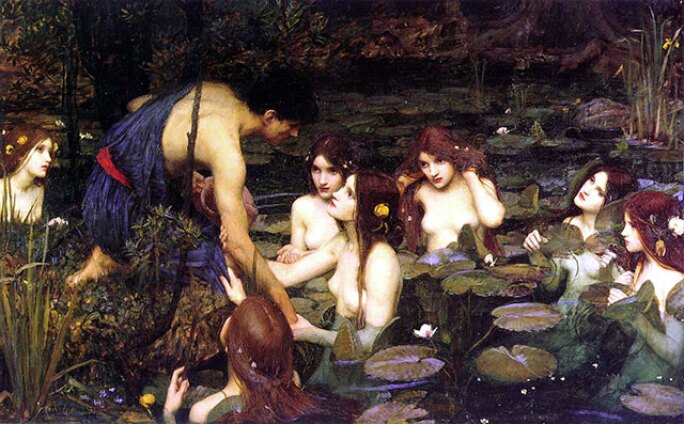

Earlier this year Manchester City Art Gallery created a sensation in the art world when they removed John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs from public display. This dark and mysterious picture of a young man at the edge of a murky black pool, from which a group of beautiful young girls rise, has become one of the most popular paintings on public view in Britain – a treasure of the Manchester collection. So why, on Friday 26 January when the last visitors had left the gallery, was the painting taken from pride of place and hidden away in storage and what was the reaction from the public the next morning?

The removal of the painting was part of an art project by British Afro-Caribbean artist Sonia Boyce inspired by the MeToo and Time’sUp campaigns. A film of the removal of the picture is presently being screened at the gallery (until 2 September). The intention was to inspire debate about the presentation of women, but as a correspondent for The Guardian noted, it created a furore; ‘Its banishment was regarded as dangerous political correctness, and the thin end of the wedge. If Waterhouse’s image of a youth surrounded by naked young women was to be taken down, where would it end? Would all our museums and galleries be dismantled, their “offensive” works, aka most Old Masters, locked away from the gaze of the public?’ (The Guardian, 7 February 2018)

The curator of the gallery Clare Cannaway insisted that there had been no intention to condemn the picture, the artist who painted it or those who have enjoyed looking it in the 122 years since it was painted. The picture was only off-view for a few days and is back on display but it had asked the question of how pictures of naked women are interpreted in the year which marks the centenary of women’s empowerment. The empty space on the wall was covered by post-it notes from the public, most of which called for the return of the beloved picture.

In a follow-up article in The Guardian Jonathan Jones wrote; ‘This painting is pretty mild stuff compared with some truly great art that, by the same logic, should immediately be removed from Britain’s galleries. The Rokeby Venus by Velázquez clearly needs to return to the National Gallery stores, where this silken nude can lie on her sensual sheets without causing offence. Titian’s Diana and Actaeon also has to go – its display of female flesh is truly gratuitous. And there is just enough time for Tate Modern to cancel its forthcoming Picasso show, which is guaranteed to contain a jaw-dropping quantity of salivating sexist visions.’ (The Guardian, 31 January 2018)

In 1896 when the picture was first exhibited, nudes were so ubiquitous in the Royal Academy exhibitions that the painting raised few eyebrows of disapproval. Most of the art critics were men and all of the Hanging Committee of the Royal Academy show were male so there were few female voices that could be heard to protest. It is interesting that in 1910 a supporter of Women’s Suffrage, Henrietta Rae painted her own interpretation of Hylas and the Nymphs – a picture with no less or more emphasis on the nude women. In 1975 when Ondine, the makers of a bath-foam, used a double-page spread in a magazine to advertise their product with a trio of nude girls recreating a portion of the picture. The titillation of this advert clearly demonstrates the prevalent sexism of the 1970s but it took forty years for the debate is raised about what the imagery of Hylas and the Nymphs represents.

What exactly does Hylas and the Nymphs depict and what do Waterhouse’s women represent? The dealer in Victorian art and author Christopher Wood described how ‘Waterhouse chooses a moment of female agency’ in this painting, the moment being the one in which the water-nymphs encircle the young boy and decide that they will seduce and then drown him. Unlike traditional Victorian depictions of women as subservient, physically weak and lacking control of their own destiny, these nymphs are very much in charge of this situation and Hylas is the one that is caught in the spider-web of their making.

The subtle eroticism in Hylas and the Nymphs inspired Waterhouse to paint a series of depictions of female water deities, including A Mermaid of 1900 (now in the collection of the Royal Academy of Art) and finding its most powerful resolution in The Siren of 1901 which will be offered in the sale of Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite & British Impressionist Art on 12 July. Rather than subrogating women or casting them as dangerous and untrustworthy, these pictures are enigmatic and we are unsure what the intentions of these women are. In The Siren the pale maiden looking down at the drowning sailor has an expression of curiosity rather than murderous appetite and it is just as likely that she may at any moment hold out her hand to help him from the surging torrents, as push him under to a watery grave.

The Siren was last seen in England in 2009 when it was one of the most memorable pictures in the major retrospective of Waterhouse’s work, held at the Royal Academy which described the artist as ‘one of Britain’s best-loved nineteenth century painters.’ In the introduction to the catalogue, Waterhouse’s modern-day biographer summarised what it is that makes Waterhouse’s paintings so popular; ‘Coursing through the pictures, across five decades, are Waterhouse’s fascination with melancholy, magic, and the thrilling dangers of love and beauty… they are lyrical in the truest sense of the word – imbued with the same hypnotic power possessed by the ancient poets who sang their stories. This was also a man particularly enthralled with female beauty and the power of women over men, over nature, over each other – no matter how sturdy or fragile they might appear physically.’

Explore more from The Art of the Season at Sotheby's