The British Museum staged the largest ever exhibition of manga outside of Japan in 2019, surveying the frenetic medium from its origins in the late nineteenth century to the £3 billion industry today. In June of that year, the museum's curator Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere sat down with Sotheby's to discuss the links between Hokusai, Instagram and contemporary artists. We revisit this interview ahead of "Manga," the second edition of Sotheby's Contemporary Showcase.

For the uninitiated, how would you define manga?

Manga is a visual form of serial narrative. It is picture story-telling through line – the quality of the line that takes you from the upper right to the bottom left of the page. Your eye follows this line. There’s a sweep. When you get used to it you can read manga incredibly quickly. It’s visceral, you enter it.

What is the biggest misconception about the medium?

That they are comics for children. The Japanese have that misconception as well. People think this doesn’t have content; that it’s just like television, a distraction. But manga has always been a strong current. And still is. In our Instagrammable world we are telling stories through pictures and manga is probably best poised to be able to do that because of its graphic line quality.

How does manga differ from a Western tradition of comics?

Comics are images in frames with text. And probably it’s equal, the text and the image. You can’t take the text out and understand what is happening. In Japan though often you don’t have text, sometimes you do but it doesn’t really matter.

What are its origins?

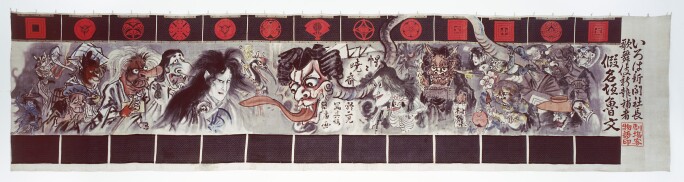

There are lots of different theories. We’re saying that modern manga came about in the 1880s because it is then that Japanese indigenous picture formats cross-fertilised with Western newspaper technology, printing and satire.

Is there a Japanese tradition of using pictures to educate?

We have an example of Hokusai in the exhibition doing this in the 18th century. It’s not a graphic novel, it’s an illustrated text book on history. Japan had high illiteracy – and this is visually led.

Has manga influenced Contemporary art?

It completely has. Manga isn’t the message, it’s a medium. It’s in Jeff Koons, it’s Takashi Murakami. If you look at Jeff Koons, he’s striving for banality, this is on purpose. He’s at a high level, quoting low; manga is from a low level, quoting high. And in a way they meet at some point.

Is it a mutual relationship? Does manga draw from other fields?

It does. Manga is a democratic form; you see reflections in it. What’s really big in manga right now is sneakers.

In 2015, Sotheby’s sold a Hergé drawing of Tintin for €1.5 million. Is Manga sold as fine art?

In France, auction houses have started to sell genga – the hand-drawn pages. There is a nascent market. I personally think people who are going to collect this medium should do so quickly because it’s going take off. And there’s a switch to digital among the younger artists, so you’re going to stop getting these formats.

How do people react when you tell them you’re a manga specialist?

I don’t tend to tell them that. My PhD is on ceramics. But ceramic artists tend to really love manga, and there’s a lot of manga about ceramics.

Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere is Research Director at the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures, University East Anglia.