T he ‘discovery’ of African Art in the West has been a journey led by artists. The position of Africa in the canons of world culture has undergone a dramatic transformation since the early 20th century, from colonially-informed ignorance to the realization that the continent from which all humanity emerged is in fact the birthplace of some of the greatest sculptural styles and artistic ideas in all of human history. Key milestones on this journey echo with a special resonance as the awakening continues today.

Two small but monumentally important African sculptures being offered at Sotheby’s on March 5 hold a special place in this story; these works, pictured below, were included in the seminal 1914 exhibition Statuary in Wood by African Savages: the Root of Modern Art at Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery 291 in New York.

This small but momentous exhibition was one of the very first – and certainly the first in the United States – to show African sculptures as art, rather than as mere specimens of ethnographical interest, in a visionary presentation which anticipated James Johnson Sweeney’s legendary exhibition, titled African Negro Art, held at the Museum of Modern Art some 20 years later.

The idea of holding an exhibition of African art in New York began with Stieglitz’s collaborator Marius de Zayas, “the chief curator” of 291. In October 1910 de Zayas traveled to Paris, where he acted as Stieglitz’s conduit to the fast-moving currents of the European avant-garde. De Zayas continually noted the important place which African art occupied in avant-garde circles, and he began to suggest to Stieglitz that they should hold an exhibition at 291, writing: “I remarked more than ever the influence of the African [...] art among these revolutionists. Some of the sculptors have merely copied it, without taking the trouble to translate it into French. I am convinced once more of the necessity of having a show.”1

The idea began to take real shape in the Spring of 1914, when de Zayas was introduced by Francis Picabia and Guillaume Apollinaire to a young art dealer named Paul Guillaume, then in the early stages of his extraordinary career. De Zayas was impressed by Guillaume, who in the years that followed would become the preeminent promoter of African art, Modigliani’s patron and dealer, and the principal advisor of Albert C. Barnes, the great American collector, for whom Guillaume’s gallery was “the Temple”, a place of aesthetic and spiritual sanctuary in which great works of both African and Modern art were displayed with equal reverence.2

In a long letter to Stieglitz written on 26-27 May, which touched upon meetings with Matisse, Gertrude Stein and the possibility of an exhibition at 291 of Picabia’s collection of Picassos, de Zayas wrote “I believe I can also arrange an exhibition […] of remarkable [...] statuets [sic]. Guilla[u]me, the art dealer, has a very important collection […] I have always believed that a show [...] would be a great thing for 291.”3

Guillaume had, in fact, written to Stieglitz just a day earlier: “I have a collection of [...] sculptures (statues and masks) and Monsieur de ZAYAS [sic] has told me to tell you about them. If it would please you to hold an exhibition of them in New York I am at your disposal [...]”.4

This exhibition at '291' showed African sculpture as art that could, on its own merits, occupy (in both a physical and conceptual sense) the same space as Modern art.

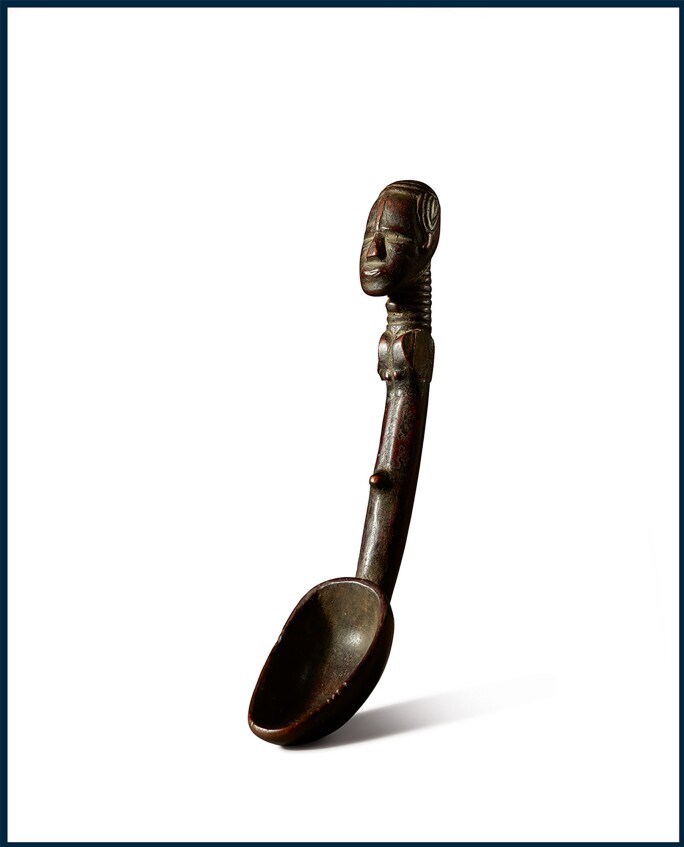

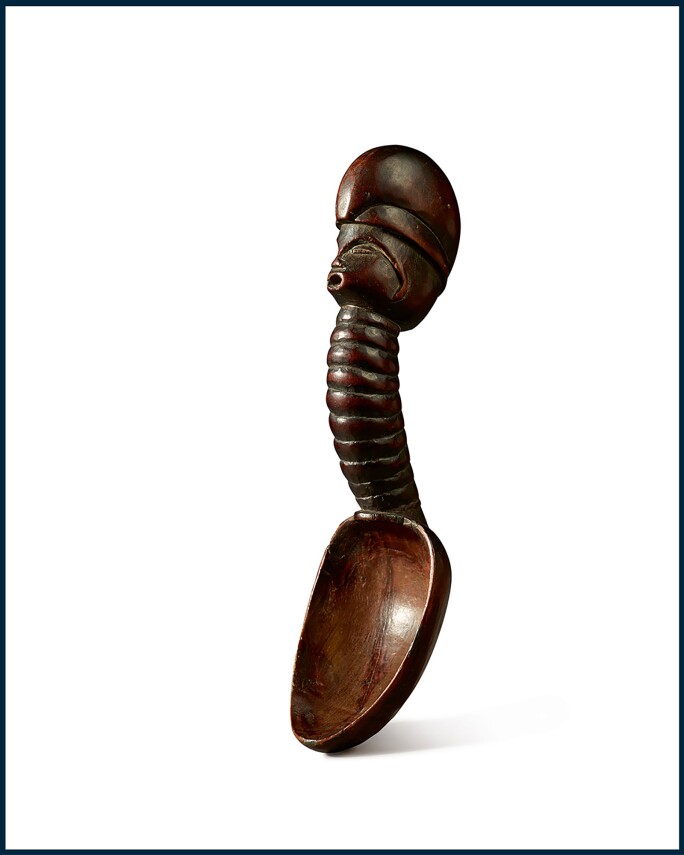

Stieglitz was enthusiastic and told de Zayas, “Of course I would like to have a show of Negro art as you know. I want to make the next season at ‘291’ a very live one”.5 So it proved to be. As the First World War began in Europe, de Zayas returned to New York from Paris with Picabia’s Picassos and a group of African sculptures from Paul Guillaume; lot 24 is from Gabon, and lot 26 is from Côte d’Ivoire. The two sculptures offered here illustrate Guillaume’s predilection for sensuous sculptures of restrained yet stylized realism, and his preference for smooth surfaces with deep, lustrous patinas.

While the exhibition at 291 arose from an interest in African art’s influence on developments in Modern art, it has a special significance because it did not show African sculpture as a “compliment” to Modern works but rather as art which could, on its own merits, occupy (in both a physical and conceptual sense) the same space as Modern art. Like the sculptures in the Brancusi exhibition that preceded it at 291, each work in Statuary in Wood was presented as an object of aesthetic contemplation, carefully framed in its own space. The pure, modernist aesthetic of the exhibition was created by the photographer and painter Edward Steichen. He placed some works on pedestals, a choice which was as simple as it was profound, since it freed the sculptures from the traditional mode of displaying them: the cluttered vitrine of the ethnographic museum. Other objects, including the two sculptures, which appear at the center of Stieglitz’s installation photograph, were mounted on sheets of yellow and orange paper, interspersed with sheets of black in a rhythmic succession of geometric forms which remove these sculptures even further from the conventions of the ethnographic museum, with its dark paneled wood and taxidermy. Steichen said that his design was intended to suggest “a background of jungle drums”;6 seen over a century later, the display of these sculptures at 291 seems to illustrate the ease with which African art was able to take its place within the pantheon of Modernism.

1. Marius de Zayas, Francis M. Naumann (ed.), How, When, and Why Modern Art Came to New York, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1996, p. 164

2. Albert C. Barnes, “The Temple”, Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life, Vol. 2, No. 17, May 1924 p. 139, cited by John Warne Monroe, Metropolitan Fetish: African Sculpture and the Imperial French Invention of Primitive Art, Ithaca, New York, 2019, p. 106

3. Marius de Zayas, Francis M. Naumann (ed.), ibid., p. 171

4. Alfred Stieglitz Papers, Series I: Correspondence, 1874-1950. Box 21, Folder 509 (Correspondence between Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Guillaume, 1914-1915), Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keeffe Archive. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

5. Marius de Zayas, Francis M. Naumann (ed.), ibid., p. 172

6. Steichen quoted by Hélène Seckel, “Alfred Stieglitz et la Photo-Secession. 291 Fifth Avenue, New York”, in Musée national d'art moderne (ed.), Paris – New York, Paris, 1977, p. 228