A ccording to the author Günter Grass, Germans who came of age immediately after the Second World War did so "with brick dust between their teeth" – which is to say, amidst the literal and metaphorical ruins of their homeland. If today’s art world is anything to go by, however, they've done a fine job of reconstruction. More than a quarter of the lots at Sotheby's Contemporary Art Evening Auction in London on 8 March are by Germans. Indeed, to roll off their names – Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter...is a little like reading a Who's Who of contemporary art.

GERHARD RICHTER, EISBERG, 1982. ESTIMATE: £8,000,000—12,000,000.

In monetary terms, Richter leads the way: the £30.4 million ($46.3 million) paid for his abstract painting Abstraktes Bild (599) in 2015 made it the second-most valuable work by a living artist ever sold at auction – after Jeff Koons's Balloon Dog (Orange). Yet, he's by no means a one-man band. Between the summers of 2015 and 2016, ten of the world's 100 most lucrative artists at auction were German. How, though, are we to explain this Teutonic rise? To some extent, it's a case of the market following where museums have led. In recent years, many of the artists in question have received retrospectives at the world's top art institutions (Richter's Panorama toured London's Tate Modern, Berlin's Neue Nationalgalerie, and Paris's Pompidou Centre in 2011/12; while Polke's Alibis toured MoMA, Tate Modern, and Cologne's Museum Ludwig in 2014/15). But that simply gets us one step closer to explaining the artists' success, rather than actually explaining it.

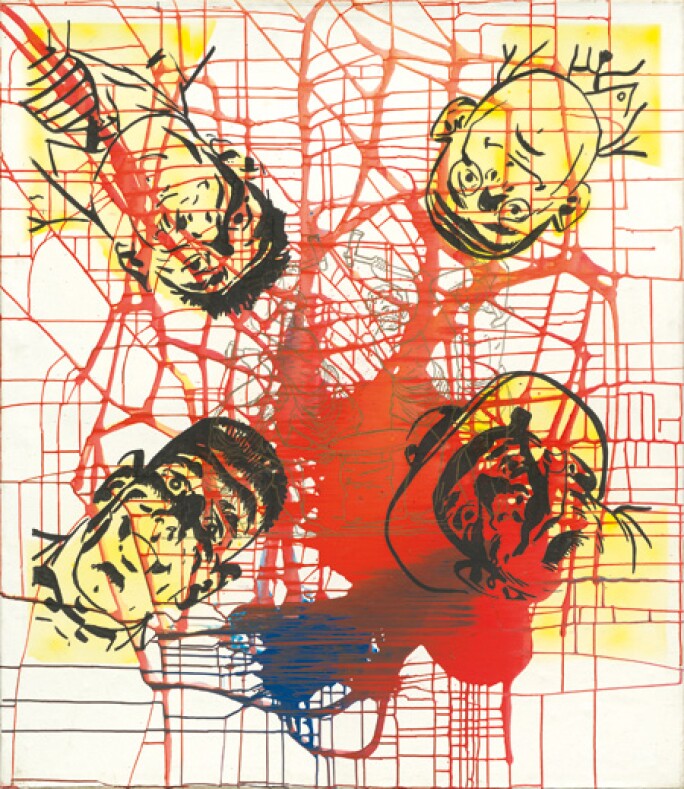

SIGMAR POLKE, DIE SCHMIEDE (SMITHY), 1975. ESTIMATE: £1,000,000—1,500,000.

They're hardly a homogenous bunch. Among them are sculptors (Günther Uecker and Thomas Schütte) and photographers (Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth), as well as a set of painters with widely different temperaments and styles. Just have a quick look at four of the paintings about to appear at Sotheby's: Baselitz's Mit Roter Fahne (With Red Flag), from his landmark series, Heroes, which features bedraggled, solitary figures in bleak landscapes; Polke's Pop Art-inspired Die Schmiede; Kiefer's Athanor, depicting a Reichstag-like building on fire; and Richter's Eisberg, a photorealistic take on an iceberg he saw in Greenland. These are works so varied it's impossible to find a winning formula that unites them.

GEORG BASELITZ, MIT ROTER FAHNE (WITH RED FLAG), 1965. ESTIMATE: £6,500,000—8,500,000.

The quality of art schools across the country is often cited as a strength of German art; Düsseldorf’s Kunstakademie and Frankfurt’s Städelschule being perhaps the most famous. Decentralisation is another factor. Unlike in, say, France or the United Kingdom, where one city – the capital – dominates and sucks the creativity from elsewhere, in Germany the federal set-up has ensured vibrant centres across the land. Gallery space in the many municipal kunsthalles offers artists the regular chance to exhibit their work, a show in Bremen, Essen, or Leipzig gaining as much kudos as one in Berlin, Stuttgart, or Hamburg.

THOMAS SCHÜTTE, UNITED BETWEEN BRACKETS, UNITED ENEMIES, 1995. ESTIMATE: £400,000—600,000.

A well-oiled system of educating and exhibiting, then, has played a part in the German advance. But art is about more than just systems, of course. It requires inspiration. And for this we can look back to the Second World War – and Günter Grass's 'brick dust'. The quartet of painters cited above were all born in the 1930s or early 1940s, Uecker likewise – and, as Baselitz himself said: "the pressure of being German really made us what we are. Without it, I don't know whether we'd have succeeded as artists."

In the wake of unprecedented Nazi horrors, an artist's role was unprecedented too. Especially as these weren't horrors perpetrated by just a guilty few in government. Every German family had some chequered connection to Nazism, every German was in some way implicated (both Richter and Baselitz's fathers, for instance, had been Nazi Party members). How, though, were artists to respond to these sins?

ANSELM KIEFER, ATHANOR, 1991. ESTIMATE: £1,500,000—2,500,000.

The default position of society at large was to ignore it. The writer WG Sebald referred to a "tacit agreement” in post-War Germany to keep "the dark aspects [of Nazism] under taboo: like a shameful family secret."

By the Sixties, however, a new generation of artists broke the silence. It was Kiefer who did so most directly and consistently – the railway track leading to a distant concentration camp in his painting Lot's Wife is but one example. Even the enigmatic Polke, though, tackled the Nazi past: swastikas became a recurring motif in his work. He also erected a wooden fence at an exhibition in Düsseldorf in the Seventies with the inscription "Art Makes You Free" – parodying the equivalent "Work Makes You Free" signs that had been emblazoned over the gates of Auschwitz and other concentration camps.

ANSELM KIEFER, LOT'S WIFE, 1989. © ANSELM KIEFER.

In truth, if one wants to see them, one can find Nazi allusions in almost any work of German, post-War art. Günther Uecker's trademark nail reliefs, for instance (one of which is on sale at Sotheby's), are often interpreted as metaphors for the injuries inflicted by National Socialism.

GÜNTHER UECKER, NAGELOBJEKT, 1958. ESTIMATE: £250,000—350,000.

It seems the art world appreciates that Richter, Kiefer and Co. are 'serious artists', who – now in their seventies and eighties (apart from Polke who died in 2010) – have been dedicated to their craft for decades. They also share a historical backstory we remain riveted by. How could a society as advanced as Germany’s – which had given the world Beethoven, Goethe and Kant – descend to such levels of inhumanity as it did between 1933 and 1945? Seen through this prism, the artists who appeared in that period's wake, and responded to it in their own idiosyncratic ways, make for fascinating – and accordingly bankable – names.

MAIN IMAGE: SIGMAR POLKE, DIE SCHMIEDE (SMITHY), 1975. ESTIMATE: £1,000,000—1,500,000.