I t is usually at the start of the lunar year and during the Dragon Boat holiday that the demon queller Zhong Kui makes his appearance, with his portraits hung prominently within homes or businesses to repel malevolent spirits and all manner of ill fortune. According to folklore, this might be accomplished by using cinnabar to paint the mythological deity at noon during the holidays, and at the same time attract good fortune to town residences.

In Chinese folklore, gui ghosts are not the only demonic figures in the supernatural world, which also include guai oddities, yao goblins, jing spirits, and mei demons. We may dismiss this as the claptrap of fairy tales and superstition, but these idea have greater significance when taken as representations of real-world ills and practical concerns. Otherworldly spirits are manifestations of disease, poverty, disaster and misfortune. Their stories are commentaries on corruption, feckless misrule and unscrupulous officials at court. Hence, protection from such evils are concerns at all levels of society high and low.

The Legend of Zhong Kui

Zhong Kui is often featured at the fore of traditional paintings. Vanquisher of demons, Zhong Kui plays an important role as a mythological guardian figure, popular in Chinese art from as early as the Tang dynasty. According to legend, he is himself a ghost who died by suicide after he was unjustly dishonoured by the emperor. This wrong was later righted, and Zhong Kui was deified as the king of ghosts and queller of demons.

Zhong Kui has his origin story as an accomplished scholar who journeyed a long way from Zhongnan Mountain to take part in the imperial examinations. He performed better than any other candidate which should have earned him high rank as an official in court. However, Zhong Kui had the misfortune of being deformed, grotesquely ugly, very slovenly, or all of the above, depending on the account. The emperor was so repulsed that upon sight he stripped the unsightly man of his honours. Outraged by this injustice, Zhong Kui dashed his head on the palace steps. He transformed into a ghost and became a fierce figure of righteousness.

Visual Representations of Zhong Kui

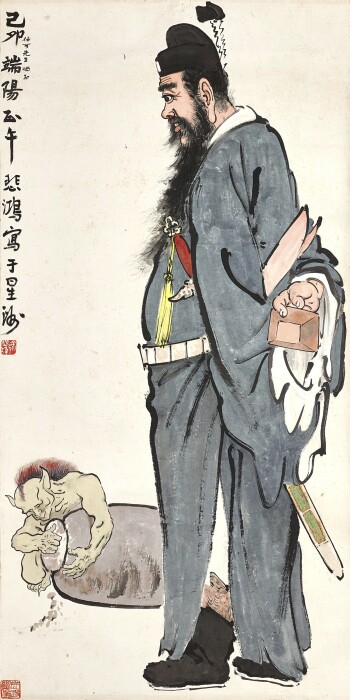

Let us look at the way different artists would evoke Zhong Kui in traditional paintings as a way of expressing historical events and contemporary conditions. Xu Beihong painted Drunken Zhong Kui in 1939, just at the critical outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Click on the red hotpots in the image of below to explore the details of the painting.

- Demons as a Sign of Adverse Times

The subject matter of the Xu Beihong's paintings would often embody patriotic sentiments and were used to stimulate national spirit. In context to China’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, which was at the backdrop during the time of this painting in 1939, the evil spirits depicted were meant to represent the invading forces of Japan.

The brushstrokes of the inscription are heavy and resolute, reminiscent of those found on ancient bronze and stone stelae from the Northern Wei dynasty. Such momentum corresponds with the conspicuous image of Zhong Kui in the painting, and is certainly telling of Xu Beihong’s impassioned frame of mind while painting.

- Drunkeness and Social Vices

Zhong Kui likes his wine and is sometimes depicted as having one too many. During these benders, the intoxicated demon queller has a tendency to let his guard down and allow demons to encroach upon order. In the painting by Xu Beihong, the demon has his head bowed as he squats with his knees bent, hugging the wine jar with one hand grasping the lid. He cautiously removes the yellow mud from the seal, for fear of smashing the pottery jar with excessive force. It is immediately apparent from the body language and solicitous demeanour that the demon is playing host to Zhong Kui by plying him with drink.

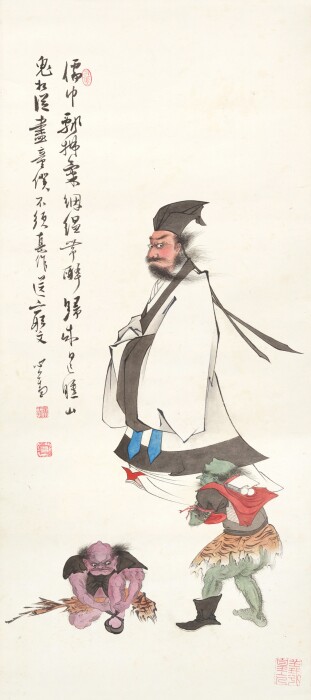

Qi Baishi, Drunken Zhong Kui . lot sold for 1,207,500 HKD. - Demon Queller

Zhong Kui is commonly depicted with a sword, befitting his role as a demon exorcist. The 11th century polymath Shen Kuo tells the story in Mengxi bitan (Conversations with a Writing Brush) of the Emperor Xuanzong who fell gravely ill from a mysterious ailment. His condition continued to worsen for almost a month, and doctors were unable to cure him. Suddenly one night, the emperor had a dream about two ghosts. The smaller one was making mischief by stealing from the imperial consort. The larger ghost caught him, ripped at his eyes and ate him. This triumphant ghost turned out to be Zhong Kui, who pledged to rid the land of evil. In the morning, the emperor woke up finding himself cured miraculously. Official Tang dynasty court documents show that during his reign, the Emperor Xuanzong gave portraits of Zhong Kui to court officials during the lunar new year as gifts.

Zhang Daqian, Demon Queller . lot sold for 764,000 HKD. Zhong Kui is often featured at the fore of traditional paintings. According to folklore, painting the mythological deity at noon during the Dragon Boat Festival using cinnabar can ward off evil spirits and bring good fortune to town residences. As a repeated subject matter of Xu’s work, the creativity and skill showcased diverge from the exaggerated freehand brushwork of Ren Bonian or Wang Yiting’s Shanghainese style. By infusing elements of Chinese brush and ink into Western sketching foundations, the figure is anthropomorphized in terms of its body proportions, facial features, physique and even skin texture, keeping in line with ideas of realism.

Pictorial Tradition and Symbolism

The depictions of Zhong Kui are full of symbolism, often carrying meanings of blessings and good auspices. Many art connoisseurs would be familiar with scenes of Zhong Kui leading his younger sister along with a supernatural retinue to marry her off to a friend. In the work by Ding Yanyong, Zhong Kui and Sister; Bamboo, a detail of the scroll illustrates the famous demon vanquisher "giving his sister away in marriage" (jia mei), which is also a homophonic pun for "quelling demons."

Although Zhong Kui was deified as king of ghosts, he is often depicted as a scholar wearing official robes, often shown with emblems of scholarship and principle. Bamboo, for example, has long been praised as the ultimate symbol of the virtuous gentleman, as the plant grows upright. Other times Zhong Kui would frequent the woods where demons lurk during the winter. There is a bit of wordplay here as "winter woods" and "scholar" are both han lin.

Besides being a vanquisher of evil, Zhong Kui has the power to bring good fortune. He is associated with auspicious symbols of Chinese iconography, for example bats or spiders.

Demons: Friend or Foe

Click on the red hotpots in the image below to explore the details of the painting.

- Unkempt and Dishevelled

Zhong Kui is depicted with a full black beard, which is an important symbol of virility and health. He is, not to put too fine a point on it, unlovely. And it isn't just because of his unfortunate physical attributes. He manages to give the impression of always being slightly rumpled or unkempt, with ill-fitting clothes that are undone, threadbare or askew. This rough look is not helped by the unruly beard which seems to encroach every which way and sets a stark contrast to the ideal image of the literati scholar.

Pu Ru, Zhong Kui . lot sold for 162,500 USD. - Demonic Attendants

As the subjugator of demons, Zhong Kui would naturally have a host of demon attendants at his disposal. The relationship can be somewhat ambivalent. At times, the creatures who act as helpful companions, scratching the demon queller's back, combing his beard, or whispering good news in his ear. But since Zhong Kui has a tendency to drink to excess, it is at these moments of drunkenness that the mischievous little demons take advantage of his dulled senses and run amok, ushering in times of rampant evil.

Qi Baishi, Scratching Zhong Kui’s Back . lot sold for 5,900,000 hkd - The Odd Shoe

As a notably untidy being, Zhong Kui would sometimes be described as having only one shoe on. The demons Zhong Kui would capture in these stories would often be similarly shod. It's an odd detail, but perhaps this deviance from proper attire is meant to suggest a disturbance in the realm, when conditions are in disorder. In a different painting by Pu Ru of Zhong Kui on a Donkey (1941), the artist wrote:

"In guilt and shame the emperor gave [Zhong Kui] a funeral with the highest honors and a place in the imperial tombs. Later, the legend says, the emperor had a nightmare that a demon wearing one shoe was robbing his apartments in the palace. Suddenly Zhong Kui appeared, and vanquished the demon. After this dream the emperor gave Zhong the title of Demon Queller and the reformed one-shoed demon became one of Zhong’s servants."

Zhong Kui Throughout the Ages

Zhong Kui is one of the most well-known figures of Chinese folklore. His image hangs on doors and walls to keep evil and misfortune at bay. Though he is a mythological figure that emerged in ancient literature from as early as the Tang dynasty, Zhong Kui persists in modern times commonly referenced in pop culture.