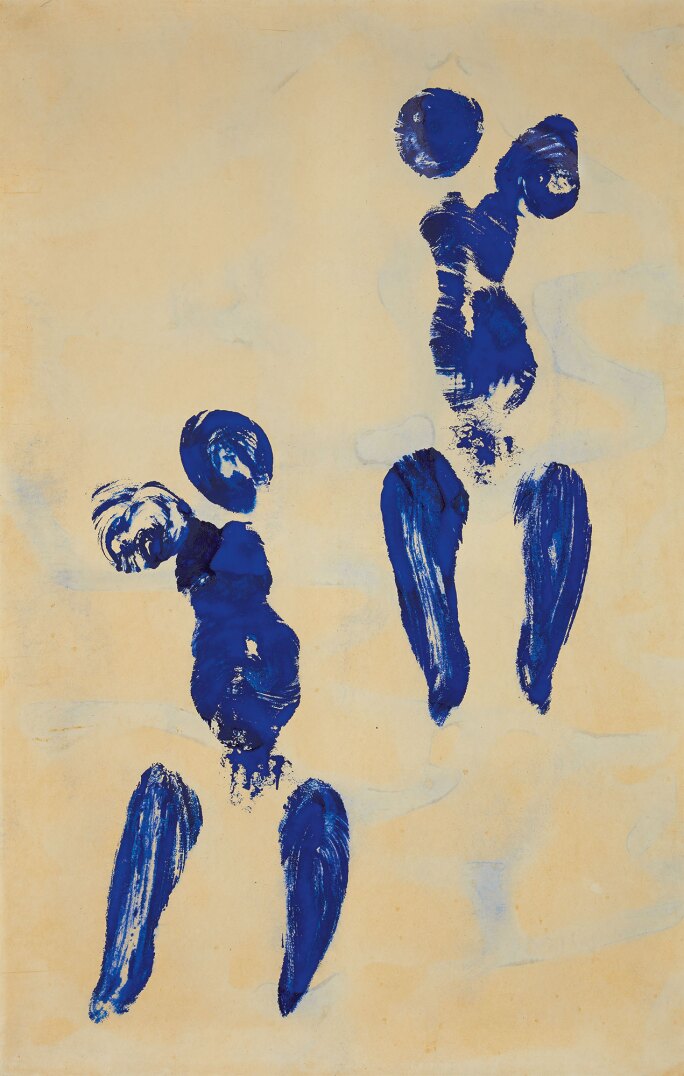

D ense in its conceptual framework and mesmerising in its elegiac beauty, Untitled Anthropometry (ANT 132) represents a distillation of the central tenets of Yves Klein’s visionary oeuvre and exemplifies the beauty of his Anthropometries. Amongst this extraordinary series, the present work is exceptional, considered rare not only for its grand-scale, but also for its inclusion of two full figures, and further still for its conception during one of Klein’s legendary performances.

In this work, using the human body as an anthropomorphic brush, Klein created a composition that set a course for a new frontier of painting, one in which the heretofore antithetical poles of abstraction and figuration achieve a stunning and groundbreaking coalescence. Untitled Anthropometry (ANT 132) is a paradigmatic example of a seminal series that has remained in one family collection for 35 years. With works such as this, Klein broke apart the very definition of painting, radicalised the enduring art historical motif of the nude, and laid conceptual foundations that have continued to inform performance art to the present day.

Untitled Anthropometry (ANT 132) was initiated during Klein’s Anthropometry performance at his Paris studio on 27 February 1960. During this performance, Klein instructed nude female models to press their paint-covered bodies against prepared sheets of paper. The sheet that forms the present work was cut from a wall-mounted frieze of paper, along which Klein’s “living brushes” pressed themselves in sequence. The model for the present work was Elena Palumbo-Mosca who had met Klein whilst working as an au pair for his friend and collaborator Arman. She later described the experience: “He knew me well, knew that I liked using my body and my energy, and also that I would strive to understand his purpose. And now what can I add? Perhaps, simply, thanks to Yves’ genius and his intrepidity, I lived a happy and intense experience of reality, having even managed to leave the trace of my fugitive presence in the uninterrupted stream of life… In fact, working in the Rue Campagne Première, it soon became clear that the creation of the Anthropometries was a kind of ritual: once we had started, the physical impregnation of my body by the blue of Yves (IKB) silently in a very intense atmosphere: Yves - like an ancient priest - just told me where to apply blue. My body impregnated with blue then became a clear symbol of vital energy” (Yves Klein Archives).

Klein conducted a number of these shamanic performances in 1960. What distinguishes the performance of 27 February, and allows us to deduce so much about the formation of the present work, is the documentary photographs by Harry Shunk who recorded the event in detail. As the resultant images show, Klein revelled in the theatre of the event; the precise orchestrations and the juxtapositions that abounded within its conception.

This event prefigured the legendary Anthropométrie de l’Époque Bleue performance, which was preceded by Klein’s Monotone Symphony, and held in front of a large audience at the Galerie National d’Art Contemporain. At each of these events, the propriety of the invited guests contrasted with the energy and drama of the performance, while the state of the performers – naked and covered in blue paint – seemed at odds with Klein’s suited attire. Works such as Untitled Anthropometry (ANT 132) exist not only as captivating objects in their own right, but also as the beautiful relics of these beguiling ceremonies. Indeed, in their appreciation, we are wholly reminded of Klein’s oft-repeated motto: “Painting is no longer for me a function of the eye. My paintings are the ashes of my art” (Yves Klein, trans. Klaus Ottman, Overcoming the Problems of Art: The Writings of Yves Klein).

The son of two artists, Klein was extremely well versed in art history. Indeed, while the Anthropometries undoubtedly presented something entirely original to the avant-garde, the likes of which had never been seen before, they can also be linked to some of Klein’s contemporaries and historical predecessors in certain stylistic aspects. The present work bears a visual similarity to Henri Matisse’s renowned series of cut-outs, such as Blue Nude from 1952, not only in its deployment of a similar palette, but also in its equitable brevity of form and comparable simplicity of composition. In this respect, the viewer is also put in mind of Robert Rauschenberg, who created works of striking aesthetic similarity using blueprint paper and photographic exposure techniques in the early 1950s.

Looking further back into art history, we are even reminded of the fragmented remnants of classical and antique sculpture. Klein’s imprint of the human form, left identifiable only by the contours of its legs and torso, recalls numerous Greco-Roman marble figures, such as the Belvedere Torso, whose full corporeal structures have fallen prey to the passage of time, and who exist similarly and solely in the rendering of the central section of their bodies. We know that Klein was enamoured by classical sculpture of this type from his well-known sculpture edition of Victoire de Samothrace, which consists of a plaster cast of the famous antique sculpture, covered in a layer of International Klein Blue pigment.

We also know that it was the central section of the body that he found most engaging and expressive in his art: “It was the block of the body itself, that is to say the trunk and part of the thighs that fascinated me… Only the body is alive, all-powerful, and non-thinking” ((Yves Klein cited in: Exh.Cat., London, Hayward Gallery, Yves Klein, 1994, p. 175)

). Klein also used his in-depth knowledge of art history and its practitioners to break away from the avant-garde and forge his own path. He had risen to prominence in the second half of the 1950s, when Abstract Expressionism reigned supreme in America, and Tachisme enjoyed stylistic hegemony in Europe. These artistic movements seemed to fetishise gesture; and glorify the individual painter’s ability to convey emotion through entirely abstract forms. Klein purposefully took a diametrically opposite approach. In imprinting the human body directly upon the canvas, he created the ultimate figurative work – as directly representative of its subject matter as possible.

Moreover, in using his models as anthropomorphic paintbrushes, he removed any sense of gesture from the finished canvas. In his Anthropometries, he appropriated the trope of the nude – that motif that for centuries had been treated with idealised sensuality – splashed it in his blue pigment and let it push itself against the picture plane with unabashed immediacy and radical intimacy. Where throughout history, the nude had stood as a test of painterly skill and draughtsmanship, it is here achieved with blatant unconcern for those conventionally held indicators of artistic dexterity. In these works, Klein deliberately dons the weighty mantle of tradition only to warp it, subvert it, and thrust it back into the creative consciousness of his viewer.

In keeping with the best of Klein’s oeuvre, Untitled Anthropometry (ANT 132) is sublime in aesthetic, charged with intellectual significance, and rich in art-historical self-awareness. In truth, it should be considered a distilled gem of conceptual verve; the glimmering residue of a preclusive performance. It acted as a precursor to countless strands of avant-garde art, and exists today as tribute to an artist at the forefront of the Parisian zeitgeist, who covered the world in his patented pigment, and leapt forth into the void.