A masterpiece of High Renaissance achievement, Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper, on the wall of the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, presents a dramatic and psychologically complex moment of the earthly and divine. “One of you is about to betray me,” Christ says to the twelve disciples seated around him. With dismayed faces and gestural hands, the disciples react in waves of emotion. Though not an uncommon subject, Leonardo’s treatment of the Passover meal broke conventions of its traditional iconography—seating all men, especially Judas, along the same side of the table, separating their spiritual realm from the viewer’s earthly one. For centuries, this famous and enigmatic work has captivated later generations of artists, as many have studied, referenced and reinterpreted Leonardo’s painting in ways that communicate complex attitudes toward religion. Artists have sought inspiration from this piece so steeped in mystery, giving way to countless reproductions and renditions throughout art history, including the four contemporary renditions by Andy Warhol, Francis Newton Souza, MADSAKI and Zeng Fangzhi, explored below.

Francis Newton Souza

F rancis Newton Souza’s reworking of one of the most recognizable images in the Western consciousness, The Last Supper was painted in 1990 and powerfully asserts a bold and towering gravitas upon enduring themes and ideas. In Souza’s reinterpretation, consternation is expressed through the Apostle’s contorted and disfigured faces. The sorrowful, downwards gaze of John who sits to Jesus’s left in Leonardo’s masterwork, is echoed in the white-jacketed figure on the left of Souza’s canvas. Christ in the 15-century imagining exhibits a similar downcast expression, whereas Souza’s protagonist stares directly out at the viewer.

Souza has depicted the aftermath of the Last Supper in some of his most celebrated masterpieces, such as in Crucifixion, 1959, and in Deposition, 1963. The Last Supper formed the origin of the Catholic tradition of the Eucharist, a subject Souza frequently illustrated in his still-life paintings of the mid-1950s to early 1960s. Painting the scene of The Last Supper decades later, Souza is signaling the pivotal importance of this event both for Catholicism and his own artistic production. Having survived a serious attack of smallpox in early childhood, Souza would return repeatedly to a dark “dream world…[born of] the phantasmagorias, the hallucinations, angels in paradise” and depict religious subjects through a monstrous aesthetic.

The faces of Jesus’s Apostles, with their high-set eyes, lopsided features and harsh outlines, are evocative of the artist’s stylized heads from the late 1950s and 60s. Art critic Edwin Mullins described Souza’s works from this early period as being "distorted to the point of destruction." This is true, however, mostly of the disciples; Jesus does not evince the same facial distortion, except for his elongated neck and enlarged features. In doing so, Souza furnishes Christ with a dignity absent from his previous monstrous and subversive depictions.

Andy Warhol

T he antithetical contrast between Andy Warhol the artist and Andy Warhol the spiritual man is central to the production of his The Last Supper series. Warhol grew up in a fervently Catholic family. His first experiences with art were of a religious nature, and the gilded Byzantine icons and crucifixes along with other religious imagery informed much of Warhol's fascination with the venerated image.

Warhol’s last and largest series of paintings which he created in 1986–87, is a magnificent summation of his core thematic concern, a grand finale to a career in which subversion and irony are the ultimate keynotes. Fine art, Pop art, celebrity and fame all intermingle in these iconic mass-produced pictures of one of the most canonical images in art history. Leonardo's famous paintings appealed to Warhol as subjects that perfectly into his aesthetic program of bringing everyday, universally recognizable imagery into the realm of fine Art. The Last Supper as an aesthetic subject combines the immortality of religion with the immortality of art.

“In this perspective these paintings can be understood as some of the most personal and revealing works of Warhol’s career.”

Warhol began The Last Supper series amid the backdrop of the emerging HIV/AIDS epidemic of the mid 1980s. There is a direct and personal connection between Warhol's fear of the mysterious epidemic, then called the “gay cancer”, and paintings like The Last Supper (The Big C), 1986, according to Jessica Beck, curator at the Andy Warhol Museum. The work depicts the image of Christ repeated four times, with Thomas gesturing beside a Wise potato chip logo, plus images pulled from motorcycle ads and headlines from the New York Post. According to Beck, “More than a demonstration of reverence for Leonardo’s masterwork, or even an unveiling of his Catholic faith, Warhol’s Last Supper paintings are a confession of the conflict he felt between his faith and his sexuality, and ultimately a plea for salvation during the mass suffering of the homosexual community during the AIDS crisis.”

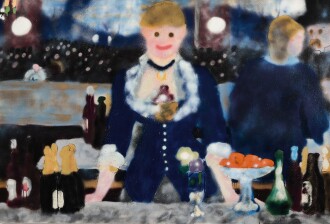

MADSAKI

I nspired by Warhol before him, Japanese contemporary artist MADSAKI sought to reinterpret images from canonical works of art history, and in the case of The Last Supper (The Big C) II (Inspired by Andy Warhol), making reference to a reference. MADSAKI uses a signature style of spray painting to rework Warhol’s composition with a sense of absent-minded, good-natured ease. The paint drips from the subjects’ eyes, and we see signs haphazard splatters throughout – together the effect is a mood of unseriousness wholly in contrast with the emotional meaning and religious heft of both Leonardo’s and Warhol’s paintings of The Last Supper. Indeed, one of MADSAKI’s figures of Christ appears almost to be smiling.

"I embrace art history itself or attempt to become one with it. I first draw the rough sketch of a masterpiece with a marker, and then I recreate it with spray paint in one go. If only for an instant, I feel possessed by an artist from the past, which gives me the illusion of acquiring freedom from this world."

The Osaka-born artist grew up in a racially homogeneous U.S. suburb. His navigation of a bicultural identity, and the incongruities of life as an outsider, must surely have had a significant imprint on the artist during his formative years. Confronted at an early age with a sense of not belonging exacerbated by a language barrier, he turned to art, drawing, and humor as his primary means of expression.

As with Warhol’s The Last Supper (The Big C), MADSAKI’s work confronts the complex identities that contrast MADSAKI the artist and MADSAKI the man. Perhaps he is best known for his Wannabe series – irreverent reworkings of canonical paintings in art history. His viewers may understandably interpret these works as straight parody. However, within them we find a sense of earnest admiration for the Old Masters, and perhaps all of the drippy eyes and smiley-faces might in fact lampoon his own discomfiture with being a serious artist. In other words, MADSAKI takes aim not at great art but at the presumption that one might even try to compare with artistic giants.

MADSAKI's work embraces the contradictions of originality and emulation, of aspiration and humility, and of tradition and subversion. It is worth considering that before MADSAKI, Warhol and Leonardo were pioneers of their time, working well outside the norm in their artistic innovation.

Other Works from MADSAKI's 'Wannabe' Series

Zeng Fangzhi

Z eng Fanzhi’s monumental The Last Supper boldly encapsulates the transforming fabric of Chinese society during the economic reform in the 1990s, and may stand as the most representative work in the history of contemporary Chinese art. Zeng took inspiration from Leonardo, an Italian Renaissance master deeply revered by the Chinese artist. Zeng’s The Last Supper is a deconstruction of the original work, substituting religious figures with masked Young Pioneers, who wear red scarves and dine on watermelons. The scrolls of calligraphic brushwork on the walls behind the figures resemble famous scriptures often seen inside classrooms. The reinterpretation of the Eucharist to classroom setting expresses a profound approach in exploring the meaning of times.

The artist's celebrated Mask series began in 1994, and examined the plight of the modern city-dweller during decade’s worth of economic growth, exploring the quandaries and anxieties of the Chinese adapting to the breakneck speed of urbanization. Stylistically, these works exude an air of Western Expressionism, but are undeniably based on Zeng’s own personal memories, steeped in distinct Chinese symbols. Within this series is the 2001 piece, The Last Supper, which presents the existential condition of the people during a period when China entered the world market, and the incongruities of the destruction and rebuilding of a society.

“All along I wanted to find an artistic voice that belonged solely to me, without being affected by any great masters.”

The Last Supper showcases an extremely mature and refined technique, situating Western Expressionism within a distinctively Chinese realm. During a period of exploration that would span over a decade, Zeng oscillated between abstract paintings and figurative renderings, eventually forging his own artistic path. The Last Supper captures a moment of societal and economic changes in China in the 1990s, while at the same time documenting the ushering in of capitalism, making it an immensely representative work within the realm of Chinese contemporary art.