F or as long as civilization has existed, humans have adorned themselves. Starting with shells, stones and bones, the love of jewellery evolved with the discovery of rare and precious materials all the way to the engineered diamonds of today. Gold jewellery, in particular, carried heavy significance in Asian civilizations. The meanings different cultures assigned to jewellery have been as varied as the designs they produce and the materials they use. Yet they are unified in the instinct to express beauty, nobility, and divinity.

Sotheby’s Golden Splendour – Gold Jewellery from the Collection of Tuyet Nguyet and Stephen Markbreiter (21-28 July, Hong Kong) presents a weeklong online auction of spectacular pieces hailing from Java, Khmer, Burma, Vietnam, and Tibet. From a collection painstakingly built over more than 40 years by two pioneers of the Asian art world, each piece is not only an exquisite work of art, but also comes with a rich history and purpose.

"Vanity may be a private characteristic, but its outward expression is molded by society. "

Beauty

Golden objects accentuate the attributes of the wearer, and their designs express a culture’s aesthetic sense. Ancient jewellery in Southeast Asia were worn by both female and male deities, queens and king, and women and men alike. Often body objects designed to accentuate beauty and status may be highly suggestive with meanings associated with fertility, eroticism, and creative power.

Power

The history of Southeast Asia is written in gold of its early kingdoms, reflecting the rise and fall of ancient empires as well as the influences of neighbouring cultures through trade, religion, and conquest. Gold jewellery throughout Southeast Asia was heavily influenced by India and religious concepts from the subcontinent. Along with the spread of Hinduism and Buddhism, India's traditions of adornment would also take root throughout Southeast Asia, eventually evolving into distinctive cultural styles.

Khmer (Angkor). From the 9th to 13th centuries, the Angkor kingdom dominated a large part of mainland Southeast Asia, holding immense wealth and controlling trade with cultures throughout Asia. As the Angkorian or Khmer empire grew more powerful, the jewellery became ever more elaborate. Sculptural depictions at temples show scenes in which warriors, celestial dancers, and nobility wore sumptuous arrangements of gold and jewels. Even Buddha, who had renounced his princely title and worldly possessions, may be depicted in regal attire with sumptuous gold and jewels; the concept of a bejeweled Buddha originated from eastern India during the 9th and 10th centuries, and was adopted by Khmer kings who appreciated the connection between kingship and divine power.

Pre-Angkor. The Pre-Angkorian civilisation, which flourished from the 1st to late 8th centuries, was renowned for their exuberant, intricate jewellery. Excavations have uncovered gold and glass beads, rings, pendants and bracelets with designs unsurpassed in later periods. The Javanese conquered part of the Pre-Angkorian kingdom in the latter half of the 8th century, and their cultural imprint can be seen in the assimilation of Indonesian motifs.

Java. One of the largest islands of Indonesia, Java was situated at the centre of maritime trade networks with India and mainland Southeast Asia, and thus had been the seat of the earliest and most powerful Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms in the archipelago. As royalty and gold were closely linked, ancient Java had a wealth of sacred gold regalia for their nobility. The highest-ranking members of Javanese royalty sported sacred gold pieces for religious ceremonies or special occasions. The pieces were similar to those seen on religious statues. In fact, everything from the placement of crowns, arm-bands, pectorals and belts follow the protocols of statues of adorned gods.

India. Gold jewellery throughout Southeast Asia was heavily influenced by India and religious concepts from the subcontinent. Kings were divinely descended, and like temple gods were decked from head to toe with gold and jewels. They were often depicted as real life gods, like the Hindu protectors of creation Vishnu or the god of destruction and transformation Shiva, while queens were adorned to resemble goddesses, like the mother of all Buddhas Prajnaparamita, Durga, or Shiva’s consort Parvati. Gold became emblematic of divine power and status, so played a central role in religious and social rites.

Divinity

The beauty and purity of jewellery was also closely linked to divinity, regarded as a way to honour or worship the gods. It is no surprise that such reverence for gold is an age-old practice, held sacred as precious material suitable for the adornment of the body, the temple of the spirit.

- Angkor

A gold, tumbled ruby and sapphire 'four-pointed star' ring, Angkor period, 9th - 13th century.

Khmers decorated their bodies, temples and deities with gold. There are very few surviving gold pieces because Khmers cremated their dead. Most gold jewellery or ornaments that survived were found hidden in caches.

Gold rings inset with precious stones, such as this remarkable four-pointed star ring, were mostly discovered in temple precincts and were likely divine offerings. Many of the rings are depicted in sculpture, worn on both hands and feet. Some of the rings were hollow to keep the weight from becoming too heavy. The high quality of the work suggest that they were created for the royal courts.

- Jaipur, India

A gem-set and enamelled 'Makara' bracelet, kada Jaipur, North India, 19th century

In India, temple grounds dancers were often ‘married’ to devidasis deities. They then dressed as the gods to whom they were bonded to purify themselves. This form of simultaneously decorating the gods and the dancers eventually found its way into jewellery worn by brides, so that they too could be purified and represented as divine.

This kada bangle is modelled in the form of two makaras with their body beautifully decorated with foiled white sapphires and green enamel. The inner shank further enamelled with peacocks and flowers. The bangle is a symbol of marriage, depicting the union and continuous circle of life and rebirth.

- Bali, Indonesia

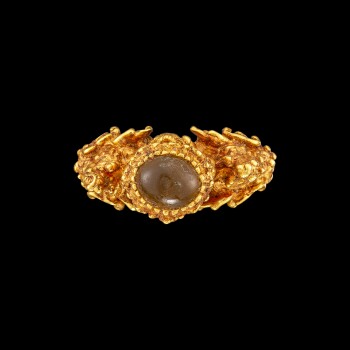

A gem-set gold 'flower and bird' priest's ring, Bali, Indonesia, 19th - early 20th century.

The jewellery of religious leaders represented power and cosmologic meaning, such as a gem-set gold 'flower and bird' priest's ring from Bali in the 19th to early 20th century. The design has birds' beaks serving as claws to hold the primary stone, a concept known from 15th-century East Java Majapahit times. It also serves as a prime example of how Balinese goldsmiths became masters of the granulation technique, small gold grains delicately soldered to a surface to create intricate designs. To finish a piece, a gold strip would folded over the primary stone, forming a collar around it.

- East Java

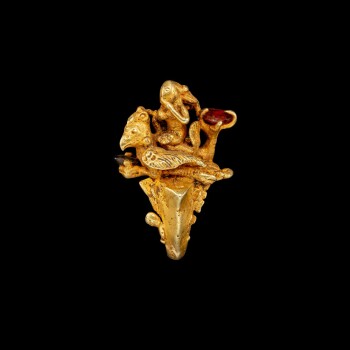

A gold 'Makara' ear clip, East Java, Indonesia, 13th - 15th century.

Makara is a symbol of darkness, commonly shown in Javanese temples in the Early Classic period opposite to Kala, the sun element. A gold ear clip from East Java from around the 13th to 15th century depicts this important symbol of the culture.

- Champa, Present-day Vietnam

A gold and cabochon ruby repoussé ring, Champa, Vietnam, 14th century.

Styles similar to a ring with Balinese granulation technique have been seen in other Asian cultures, like a gold and cabochon ruby repoussé ring in the collection from 14th century Vietnam. Shaiva Hinduism was first recorded religion of the Champa, and it remained the predominant belief until the 16th century.

- Tibet

A gold and coral saddle ring, Tibet, 18th - 19th century.

Early gems were endowed with supernatural force. The use of prophylactic stones was widespread in Tibet and Nepal. They were thought to represent the universe and take on the characteristics of the ruling planets. Coral, for instance, was associated with Mars. A striking gold and coral saddle ring from 18th to 19th century Tibet may have been worn for strength and protection, as well as to ward away fever and kidney disease.

- Indonesian archipelago

A gold 'snake' necklace with stone-set eyes Possibly Flores or Sumba, Indonesian archipelago, 19th century.

In Sumba, gold ornaments were create to honour ancestors, and noble houses would compete in supreme displays of wealth in ceremonies. Gold had been regarded as a material of divine origin with the sun as its source, and its melted form was invested with power.

- Jaipur, India

A rare gold, diamond, ruby and emerald 'bird' ring, Jaipur, North India, 19th century.

This uncommon ring in the form of a bird set with diamonds, rubies and emeralds has a reverse enamelled with a peacock in red, white, blue and green meenakari. In Indian custom, the ring assumes a paramount place as it is the intermediary medium between the physical and spiritual realm.

- Northern Thailand

A gold 'snake' ring set with ruby eyes. Northern Thailand, 18th century or earlier.

Snake or dragon rings were found at the courts of Burma and Java, and were worn exclusively by members of the royal family.

- Leyte, Philippines

A pair of gold earrings with floriated spangles, Leyte, Philippines, 10th - 13th century.

In the Philippines, styles of gold working differed from areas such as Malaysia, Sumatra and Java, which had more interaction with external influences. The jewellery style derived from Indian forms appeared less in the eastern parts of the region.

John Cary’s 1801 “A New Map of the East India Isles, from the Latest Authorities.”

Afterlife

"Gold which heralded new life, now transports the departed soul. "

Gold remains prized today for its enduring quality. Sacred gold pieces such as bracelets, beads and masks were often commissioned to honour ancestors. In some cases pieces made from other materials would be covered in gold fold in order to express this connection between gold and the afterlife. Jewellery was often a part of burial ceremonies or perhaps to promote transcendent communication by conjuring spirits, to honour deities or to invoke ancestors.

The Malayo-Polynesians, whose ancestors settled in the Philippines around 5,000 years ago and eventually spread through Indonesia and Malaysia, were known to make gold masks for those that passed on.

At Giong Lon in southern Vietnam, three gold masks dated to the two centuries between 100 BC and 100 AD, have also been found. These have artistic differences but likely stem from the same traditions. The oldest scientifically elated gold in insular Southeast Asia has been found in Bali, which has no gold but where it was used to bury the dead between 100 BC and 100 AD.

The burial offerings included gold cones, beads of round and discus shapes, leaf-shaped eye and mouth covers and beads of glass and shell. A gold ring was discovered outside a burial ground from that period. The theory is that it may have been imported from India around 1,800 years ago, as finger rings were not common in Southeast Asia.

Much mystery remains about the jewellery of ancient Asia. The purpose of specific pieces may be lost to time, but some of the treasures of those bygone kingdoms are now available at Golden Splendour – Gold Jewellery from the Collection of Tuyet Nguyet and Stephen Markbreiter auction.