W hat could be more beautiful, more simple, more poetic than this 'Éventail' table by Charlotte Perriand? So imposing, sober and elegant that upon seeing it, one says to oneself that it should have always existed. That is exactly the Perriand touch: this art of inventing something from almost nothing, shifting the gaze, thinking about the material and the purpose, then taking these elements and imagining something new.

Not new in a disruptive sense, which is obvious, which stands out, but as a timeless object which should have existed before and which arrives in the natural order of things to take its place as if it was always there. The poetry of Ponge comes to mind, as does Dubuffet's art brut, Calder's mobiles and of course the forms of Fernand Leger, with whom Perriand liked to walk on the beaches at low tide to collect pieces of driftwood that she installed inside her houses as if they were works of art.

The Beguiling Minimalism of Charlotte Perriand's Design

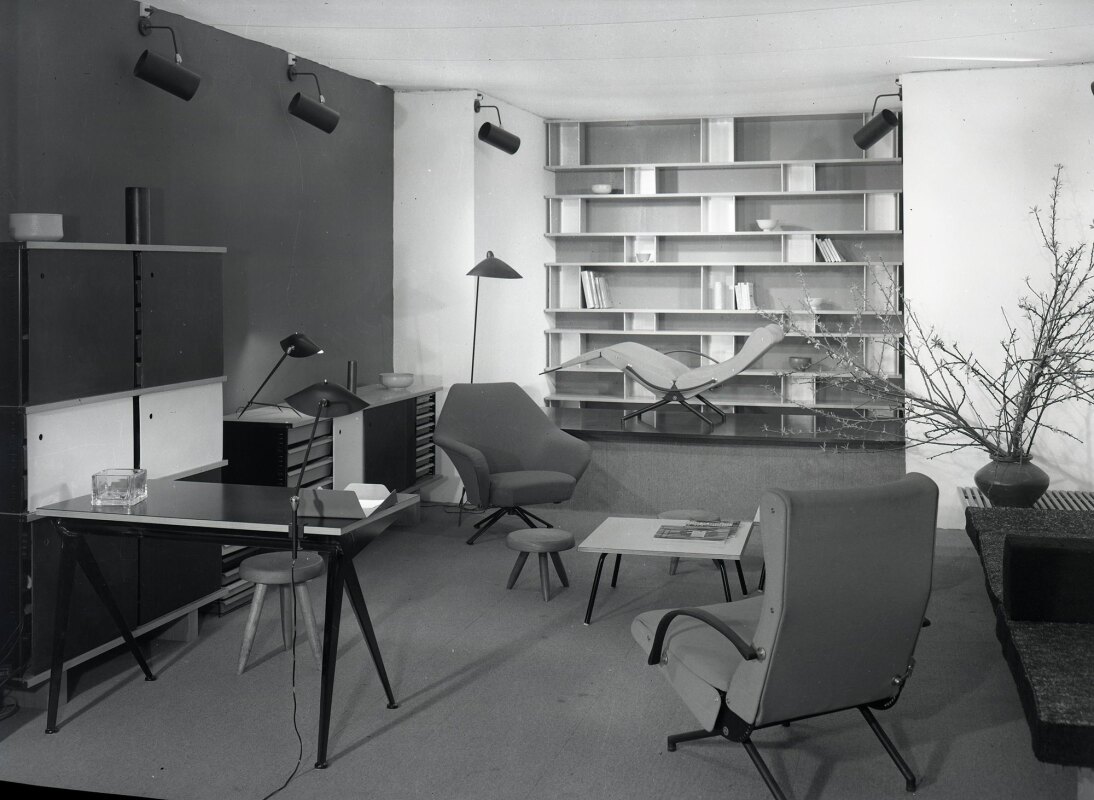

The Vietnamese researcher who commissioned this table was directed to Perriand by his architect, who likely discovered her furniture at the Galerie Steph Simon in Paris, of which she was the artistic director and where furniture and objects by her, and Jean Prouvé, were sold. When she accepted the proposal, it was probably because the customer was able to establish a dialogue with her right from the outset.

That's the way Perriand was: she liked to know what would become of what she created, how it would be used and by whom. Even though she was internationally recognized at the time, she retained this down-to-earth side and hated anything that was showy or tacky – precisely what we would call the decorative.

With the Galerie Steph Simon, the forerunner of modern furniture for both industrial and private projects, Perriand designed the pieces that he would have then made. This “fan” table in pinewood was initially intended for the chalet in Méribel, but for reasons unknown, it never left for the mountains. It is this unique object that she had designed for herself that the researcher fell in love with. He found it too "raw" though, and suggested that Perriand change the wood. She adapted the original model and changed the proportions to make a desk that allowed the researcher to spread out all his papers in front of him. Solid dibetou wood was chosen and the table executed by Perriand's carpenter friend.

Unfortunately, we do not know how the researcher and his wife reacted to their commission. What we do know is that they shared the same idea of space and light, that they wanted a house to live in and for them, living was being able to see the landscape outside from the inside.

Perriand is constantly being discovered and rediscovered by audiences of different generations and by very different artistic sensibilities. The exhibition at the Fondation LVMH allowed visitors to become aware of the vastness and variety of the media she worked in and the continuity of a body of work that never strayed from its fundamental values: a certain idea of beauty, freed of all ornamentation, a purity, an approach that seeks to find the essential, the inner balance.

It is not to be believed, however, that Perriand arrived at this kind of result by brilliance alone. Everything Perriand created was the result of an artistic impulse backed by technical research of high precision. It is perhaps this alliance of the material and the spiritual that we call grace.