D istinguished by his remarkable generosity, unfailing politeness and meticulous eye, David Teiger was one of the great patrons and collectors of our time. Driven by a desire for inspiration and buttressed by meticulous research, Teiger built a collection that perfectly captures the zeitgeist of the art world from the 1990s through the 2000s. Defining excellence in a wide variety of collecting categories, Teiger insistently pursued the very best.

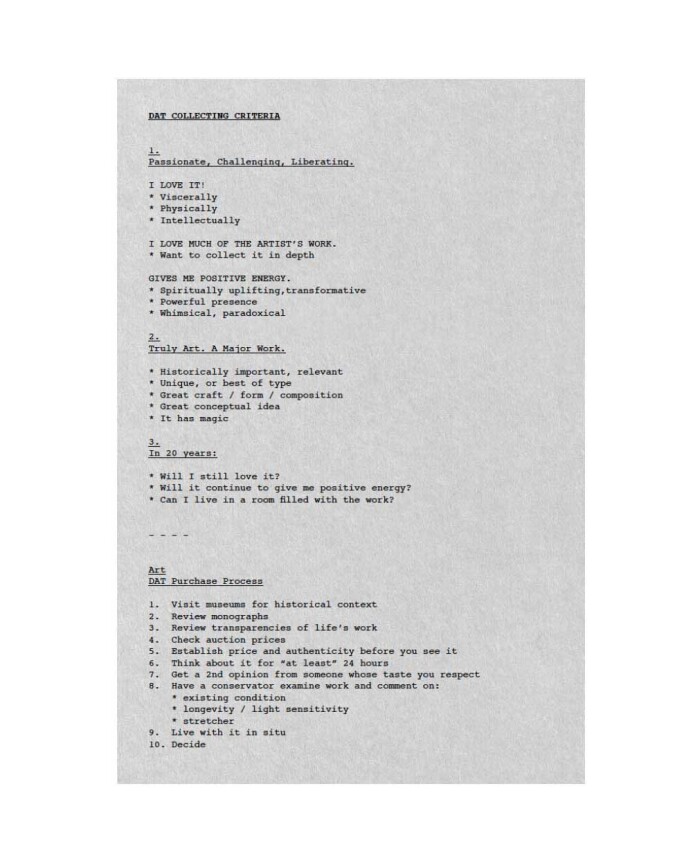

The criteria by which Teiger collected were remarkably consistent, and were summed up in a quote he gave to The New York Times in 1998, when he first began acquiring contemporary artworks. He said: “I’m looking to be inspired, motivated, titillated by art. I want to be surrounded by objects that give me positive energy… Of course I want first rate pieces. I look for authenticity, integrity, original natural surface and a strong sense of colour and texture. But the most important thing is that I react in my gut”.

Years later the terminology changed but the requirements remained the same; for all his meticulous research and careful consideration of every purchase, Teiger still required that an item “have heat”, an intrinsic quality that would combine with other criteria such as “best of type”, “great craft” and “powerful presence” to qualify a work for admission to Teiger’s collection.

Amassed over the course of twenty years, the David Teiger Collection is wide ranging in its scope, comprising a spectacular array of contemporary artworks, from paintings and works on paper to photographs and prints, and one of the greatest collections of American folk art in private hands. Famously exacting, each purchase would necessitate an extraordinary depth of research, often including multiple studio visits.

The works offered here are testament to those guiding principles that Teiger imposed on himself. From Chris Ofili’s politically charged Adam and Eve tableau, Afro Love and Envy, to Glenn Brown’s journey through the canons of art history, and Jeff Koons' audacious take on classical imagery.

Senile Youth epitomises the position of the artist's work at the intersection of art and technology, appropriation and invention. Based on Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s painting Diana and Endymion (National Gallery, Washington D.C.), Brown presents us with a back-lit theatrical monstrosity that apes Fragonard’s painting; the peaches, pinks and blushing reds replaced by a deathly blue pallor punctuated by violent bursts of vermillion, smooth and limber flesh supplanted by veined and distended body parts.

Glenn Brown frequently refers to himself as an appropriation artist whose works are entirely contingent on the canon of art history, and indeed Life is Emprty and Meaningless is as reminiscent of Frank Auerbach’s portrait paintings, as it is of Vincent van Gogh’s expressive brushmarks, or Salvador Dalí’s surrealistic dreamscapes. With its melancholic demeanour and downcast gaze, the work evokes a plethora of seminal artworks from Henry Fuseli’s drawing The Artist’s Despair Before the Grandeur of Ancient Ruins (1778-80) to Pablo Picasso’s poetic rendering of The Old Guitarist, (1903-04), from the Blue Period.

Starting with an image by a canonical artist Brown implements a metamorphosis of distortion and inversion. Colours are altered, formations cropped and stretched, compositions mirrored and flipped – the work is made to bend to the artist’s will. In so doing, Brown breathes new life into the works of often long-dead artists. In his words, “I am rather like Dr. Frankenstein, constructing paintings out of the residue or dead parts of other artist’s work”.

Created in 2002-03 and prestigiously included in Chris Ofili’s critically acclaimed British Pavilion exhibition for the 2003 Venice Biennale, Afro Love and Envy belongs to the artist’s seminal Within Reach series. Rendered in the tricolour of Marcus Garvey’s Pan-African flag – red, black and green – this group of paintings narrate a primordial creationist story; an Aforcentric tale of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. In Ofili’s resplendent Afro Love and Envy, two lovers kiss underneath the tropical boughs of an idyllic paradise inspired by the artist’s residency in Trinidad three years prior. Depicting lovers embracing under a palm tree, this clichéd trope of a tropical holiday romance became a springboard for the series’ utopian love story.

Executed in 1988, Christ and the Lamb comes from one of Jeff Koons’s most celebrated body of works, Banality. Comprising an assortment of wood and porcelain sculptures and, as in the present work, ornately framed mirrors, Koons’s Banality series represents the artist’s most elaborate and dedicated response to the mechanics and dynamics of appropriation. The works draws from an array of sources that range from the sacred to the profane, the revered to the banal, creating a compelling interplay between so-called ‘high’ art and ‘low’ culture. The silhouetted image has been directly borrowed from a scene in Leonardo da Vinci’s canonical oil painting The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, circa 1503, housed in the Louvre, Paris.

“In the Banality work, I started to be really specific about what my interests were. Everything here is a metaphor for the viewer’s cultural guilt and shame... These images are aspects from my own, but everybody’s cultural history is perfect, it can’t be anything other than what it is – it is absolute perfection. Banality was the embracement of that.”

— Jeff Koons